Izmail State Liberal Arts University

Ukrainian ministry of Higher education

The chair of English Philology

Report

The House of York

Written by

2nd year student

English-German department

Of Faculty of Foreighn Languahes

Elena Blindirova

Izmail, 2004

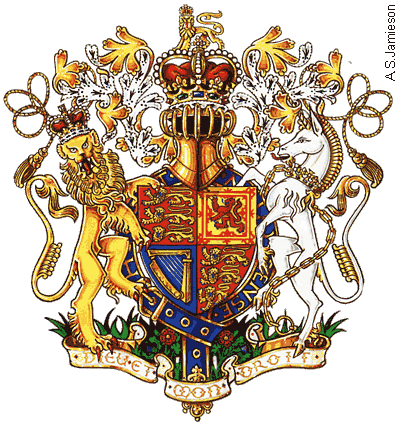

House of York royal house of England, deriving its name from the creation of Edmund of Langley, fifth son of Edward III, as duke of York in 1385. The claims to the throne of Edmund's grandson, Richard, duke of York, in opposition to Henry VI of the house of Lancaster (see Lancaster, house of), resulted in the Wars of the Roses (see Roses, Wars of the), so called because the badge of the house of York was a white rose, and a red rose was later attributed to the house of Lancaster. Richard's claim to the throne came not only from direct male descent from Edmund, but also through his mother Anne Mortimer, great-granddaughter of Lionel, duke of Clarence, who was the third son of Edward III. The royal members of the house of York were Edward IV, Edward V, and Richard III. The marriage of the Lancastrian Henry VII to Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Edward IV, united the houses of York and Lancaster. Henry was the first of the Tudor kings.

The representatives of the House of York

The House of York

Edmund, 1st Duke of York, 1341–1402

Named Edmund of Langley after the manor where he was born, he was the fifth son of Edward III and Queen Philippa. Created Earl of Cambridge in 1362, he joined his brother John, Duke of Lancaster (John of Gaunt) in his wars against Castile. In 1372, he married his first wife, Isobel, younger daughter of Peter, King of Castile and Léon, while her elder sister married John. They had three children: Edward Plantagenet, 2nd Duke of York; Constance of York, Countess of Gloucester, and Richard, Earl of Cambridge. Created Duke of York by Richard II in 1385, he retired from public life after Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, seized the crown from Richard II. After the death of Isobel in 1394, he married Joan, daughter of Thomas Holland, Earl of Kent.

His arms were: Quarterly, France ancient and England, over all a label of three points argent each point charged with three torteaux; and his crest on a cap of maintenance gules turned up ermine, a lion statant guardant crowned or, gorged with a label as in the arms; on his seal, the arms are supported by two falcons, each holding with beak and claw a long scroll, which extends backward over body, inscribed with the motto "None other".

Edward Plantagenet, 2nd Duke of York, 1373–1415

The elder son of Edmund of Langley, he was created Earl of Rutland in 1391. Richard II made him Lord High Admiral and Warden of the Cinque Ports and in 1397, Duke of Albemarle. In the first year of the reign of Henry IV he became involved in a plot to assassinate the king at a tournament at Oxford. His father went to warn the king, but Edward forestalled him by confessing to the king himself. He lost the dukedom but was pardoned, becoming Duke of York on his father’s death. He was killed at the battle of Agincourt, where he led the vanguard. He died without issue and was succeeded by his nephew Richard.

His arms were: as Lord High Admiral, Per pale, dexter, the attributed arms of Edward the Confessor, charged overall with a label of three points; sinister, Quarterly, France ancient and England, over all a label of five points argent, each charged with three torteaux. After he became Duke of Albemarle, his arms were: Quarterly, France ancient and England, over all a label of three points gules each charged with three castles gold. As Duke of York, they were: Quarterly France modern and England, over all a label of York.

Constance of York, Countess of Gloucester, 1374–1416

The only daughter of Edmund of Langley, Constance was the mistress of Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent, by whom she had a daughter named Eleanor. She later married Thomas le Despencer, Earl of Gloucester. Two children, Richard, Lord le Despencer, and Elizabeth le Despencer, died without issue, but their daughter Isabel le Despencer married twice, her second husband being Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. Their daughter, Anne Beauchamp, married Richard Neville (The Kingmaker), who thus became Earl of Warwick.

Constance bore the arms of her father, Edmund of Langley, impaled by those of her husband, which were: Quarterly, first and fourth, or, three chevronels gules; second and third, Quarterly, argent and gules, a fret or, overall a bendlet sable.

Richard, Earl of Cambridge, 1376–1415

Named Richard of Coningsburgh, after the place in Yorkshire where he was born, the younger son of Edmund of Langley was created Earl of Cambridge in 1414. In the following year, however, he conspired with Henry, Lord Scrope, and Sir Thomas Gray to assassinate the king, Henry V. He may have been bribed by the French king, Charles VI, or it may have been because, in the event of his brother-in-law Edmund, Earl of March, dying without issue, his own son would have been next in line for the throne. The Earl of March revealed the plot to the king, and Richard was executed.

Richard’s first wife, Anne Mortimer, was sister and afterwards heiress to the Earl of March and to the claims of her great-grandfather, Lionel, Duke of Clarence, second son of Edward I, thus giving her Yorkist successors a superior claim to the throne over the House of Lancaster. Richard of Coningsburgh’s second wife was Matilda, daughter of Thomas, Lord Clifford.

His arms were: Quarterly, France first ancient, later modern, and England, over all a label of three points argent each charged with as many torteaux, within a bordure argent charged with lions rampant.

Anne’s arms were: Quarterly, first and fourth, barry of six, or and azure, on a chief of the first two pallets between two base esquires of the second, over all an escutcheon argent; second and third, or a cross gules, impaled with those of her husband.

Isabel, Countess of Essex, 1409–1484

Isabel was the oldest child of Richard of Coningsburgh and Anne Mortimer. Her husband Henry Bourchier, second Earl of Eu in Normandy was created Viscount Bourchier by Henry VI and Lord Treasurer of England. William, the eldest of their ten children, married Anne, sister of Elizabeth Woodville.

The Bourchier arms: Quarterly, first and fourth, argent, a cross engrailed gules, between four water bougets sable; second and third, gules, billety and a fess or, and their crest A man’s head in profile with sable hair and beard, ducally crowned or, with a pointed cap gules.

Richard, 3rd Duke of York, 1411–1460

Richard was the only son of Richard of Coningsburgh, and the only male, apart from Henry IV, with an unbroken male descent from Henry III. Although his father had been executed for treason, Henry VI restored to him the titles Duke of York, Earl of Cambridge and Rutland. An honorable man, his superior claim to the throne and obvious capability compared with the weak and mentally afflicted Henry VI earned him the hatred of the Queen, Margaret of Anjou. His wise and just rule in Ireland during 1449–1450 laid the foundation for an Irish–Yorkist alliance which survived until after the defeat of Richard III at Bosworth.

Made Protector of England in 1454 during Henry’s temporary insanity, he defeated an attempt by the Queen and the Earl of Somerset to regain control when, in 1455, along with the earls of Warwick and Salisbury, he defeated the king’s forces at St Albans. He was made Constable of England, but the Queen’s party regained power the following year. In 1459 the Queen felt strong enough to to crush the Yorkist party and in October the Yorkist forces, surrounded at Ludlow, were forced to flee. The Duke and his second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, fled to Ireland while Warwick and his party went to Calais. Within a year, Warwick was back in England and in control of London. The Duke of York returned and on October 10 laid his hand on the empty throne in the chamber of the Lords in parliament, claiming the crown. His bid for the throne was premature, but the Duke was eventually recognized as heir to the throne, Prince of Wales and Protector of England.

The Queen’s party rallied once again, however, and on 30 December 1460 the Duke’s forces, issuing from Sandal Castle clashed with the Lancastrians at Wakefield. The Duke was killed, along with his son Edmund, and their heads were exposed on the walls of York. They were later buried at Pontefract and then at Fotheringhay.

His arms were: Quarterly, France modern and England, over all a label of three points each charged with three torteaux, and upon his helmet his crest was On a chapeau gules doubled ermine, a lion statant guardant crowned or, gorged with a label as in the arms.; the badge with which he is particularly associated is the silver falcon and gold fetterlock, the fetterlock open to symbolise the release of the falcon and the aspiring hopes of gaining the crown.

Cicely Neville, Duchess of York, 1415–1495

The wife of Richard, 3rd Duke of York, Cicely Neville was the daughter of Joan Beaufort, the youngest child of John of Gaunt and Catherine Swynford. Her father was Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland. Known in her youth as the Rose of Raby, after her birthplace, Raby Castle, she was a staunch supporter of her husband, spending as much time with him as was possible in that troubled age. They had eight sons and four daughters, of whom four sons and one daughter died young.

After the tragic death of her husband and second son, Edmund, in 1460, Cicely shortly witnessed the triumph of her eldest son Edward. She is reported to have been outraged by his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. Further tragedy followed when, in 1478, Edward tired of the treacherous behaviour of his brother Clarence and the latter died, or was killed, in the Tower. In 1483, Edward died, and then, in 1485 her last surviving son Richard III was killed at Bosworth. Outliving all her sons, the unfortunate duchess lived to see many of their progeny murdered by Henry VII and the House of York destroyed. In 1480, she became a Benedictine nun at Berkhamsted, where she lived until her death.

Her arms were: a falcon rising, ducally gorged, bearing on its breast a shield of arms, Per pale, dexter, Quarterly, France modern and England; sinister, gules, a saltire argent, supported by Dexter, an antelope gorged with a coronet; sinister a lion.

Children of Richard, Duke of York and Cicely Neville

Anne of York, Duchess of Exeter, 1439–1476

Eldest daughter of Richard, Duke of York, she was first married to the Lancastrian Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter and Lord High Admiral. She divorced her Lancastrian husband in 1472 and married Sir Thomas St Leger, K.G., by whom she had a daughter, Anne, whose descendants became the earls and later dukes of Rutland.

Her arms were: Per pale, dexter, Quarterly, France modern and England; sinister, per fess, de Burgh and Mortimer.

Edmund of York, Earl of Rutland, 1443–1460

Edmund was born in Rouen, France, while his father was serving as Lieutenant of France. At the age of seven, Edmund received his education at Ludlow Castle, along with his brother Edward. When his father’s Yorkist party fell out of favor in 1459, Edmund accompanied his father to Ireland, where he was created Earl of Cork.

After the Yorkist victory at Northampton September 1460, he returned to England and headed north to Sandal Castle with his father to help quell disturbances there. Edmund was killed at the battle of Wakefield on 30 December 1460, by Lord Clifford, whose father had been killed at the battle of St Albans. As he struck the fatal blow, Clifford allegedly cried ‘By God’s blood, thy father slew mine and so will I do thee and all thy kin. His arms were: Quarterly, first, Quarterly France modern and England, a label of five points argent the two dexter points charged with lions rampant purpure and the three sinister points each with three torteaux; second and third, Burgh; fourth, Mortimer.

Elizabeth, Duchess of Suffolk, 1444–1503

The second daughter of Richard, Duke of York, and Cicely Neville married John de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, whose father, William, had arranged the marriage between Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou. John de la Pole, whose mother, Alice, was the grand-daughter of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, took little part in politics. The couple had seven sons, of whom the eldest was also named John (see below). Edmund de la Pole was beheaded by Henry VIII and the last de la Pole heir, Richard, was killed at the battle of Pavia in 1524, fighting for the French.

The arms of John de la Pole were: Quarterly, first and fourth, azure a fess between three leopards’ faces or; second and third, argent, a chief gules, over all a lion rampant double queued or; and his crest was An old man’s head gules, beard and hair gold, with a jewelled fillet about the brows.

John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln 1464?-1487

The eldest son of Elizabeth and John, Duke and Duchess of Suffolk, was created Earl of Lincoln in 1468. He was also made a Knight of the Bath in 1475 and attended his uncle Edward IV’s funeral in April 1483. He bore the orb at the coronation of another uncle, Richard III, in July 1483 and became the president of the Council of the North. He was declared heir to the throne by Richard III in the event of the death of his own son, Prince Edward. At this time, he was also created Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and was given the reversion to the estates of Lady Margaret Beaufort, subject to the life interest of her third husband, Lord Stanley.

A staunch supporter of Richard III, he fought at Bosworth and survived. The new king, Henry VII, had no wish to alienate the de la Pole family and appointed John a justice of oyer and terminer the following year. In 1487, he fled to Brabant and then to Ireland, where he joined the army of the pretender Lambert Simnel. He was killed at the Battle of Stoke in June 1487. Shortly afterward, he was attainted.

He was married twice: (1) Margaret Fitzalan, daughter of Thomas, twelfth Earl of Arundel; and (2) the daugher and heiress of Sir John Golafre. He left no children from either marriage.

Arms of John de la Pole: Same as above during his father’s lifetime, differenced with a label argent – or his father’s and mother’s impaled.

Edmund de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, 1472?-1513

Edmund de la Pole was born about 1472, the second son of John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, and Elizabeth, sister of Edward IV. In 1481 Edward IV sent Edmund to Oxford. He was created a Knight Baronet at Richard III's coronation. He was also present, with his father, at the coronation of Elizabeth of York on 25 November 1487 and was frequently seen at Henry VII's court.

His father died in 1491, and as eldest surviving son, should have inherited the dukedom but did not, due to an Act of Attainder against his brother John, Earl of Lincoln. By an indenture date 26 February 1493, Edmund agreed to forego the title of duke and was created an earl. He also had to pay £5,000 for the restoration of some of his lands.

In October 1492 Edmund was at the siege of Boulogne. On 9 November 1494 he was leading challenger at Westminster in a tournament which created Henry (later Henry VIII) Duke of York.

In 1495 Edmund was appointed trier of petitions from Gascony and other parts. He was created a Knight of the Garter in 1496. In February 1496 he was one of the English noblemen who stood surety to Archduke Philip for the observance of new treaties with Burgundy.

On 22 June 1496 he led a company against Cornish rebels at Blackheath. Two years later, he was indicted at the King's Bench for murder and received a pardon. Although he resented being arraigned (as one of royal blood) he attended a Chapter of the Garter at Windsor in April 1499.

In July or August 1499 Edmund fled to Guisnes and then to St. Omer. Henry VII instructed Sir Richard Guldford and Richard Hatton to return him by any means. However, he returned to England voluntarily and was restored to favor.

Edmund was a witness at the marriage of Arthur to Catherine of Aragon in May 1500 and then went with Henry VII to Calis where he stayed until August 1501. He fled to Emperor Maximilian in the Tryol. Maximilian had promised support to anyone of Edward IV's blood.

On 7 November 1501 Edmund and his supporters were proclamimed traiors at St. Pauls Cross and was outlawed at Ipswich on 26 December 1502. He reclaimed his dukedom. Maximilian then promised not to aid any traitors to England (he was paid 10,000) and Edmund remained at Aix le Chappelle until Easter 1504. In January 1504 Edmund and his brother, William and Richard, were attainted by Parliament. He left Aix fro Gilderland and was immediately thrown in jail.

On 24 January 1506 Edmund commissioned two servants to treat with Henry VII and in March 1506 was conveyed to the Tower. Henry had given Archduke Philip his written promise not to execute Edmund.

Upon the accession of Henry VIII in 1509 Edmund was not among those included in the general pardon. He went to the block in 1513.

Edmund married Margaret, daughter of Richard, Lord Scrope and had one daughter Anne, who became a nun at Minories within Aldgate. He had no male heir.

Richard de la Pole, 14?-1525

Richard was the fifth son of John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, and Elizabeth, sister of Edward IV. His brothers Humphrey and Edward took orders in the Church, Edward becoming the Archdeacon of Richmond. In 1501 Richard fled abroad with his brother Edmund. Three years later he was attainted along with his brother. Eventually he fled to Hungary, where Henry VII requested that King Ladislaus VI surrender Richard to him. The Hungarian king refused and gave Richard a pension.

Richard’s name is not mentioned in the general pardon issued by Henry VIII upon his accession in 1509. Louis XII of France recognized Richard as king of England, giving him a pension of six thousand crowns. After the execution of his brother Edmund in 1513, Richard assumed the title of Duke of Suffolk and became a claimant to the English throne.

When Louis XII died in 1515, his successor Francis I continued Richard’s allowance. As a further sign of favor, he was sent him on several missions, including Lombardy and Bohemia. In 1522, Francis seriously thought of sending Richard to invade England, but the invasion did not take place.

On 25 February 1525, Richard was killed, fighting in the French army at the Battle of Pavia. The Duke of Bourbon was one of the chief mourners at his funeral.

Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy, 1446–1503

Born at Fotheringhay, Margaret, the third daughter of Richard, Duke of York, and Cicely Neville, was an intelligent, charming, and accomplished woman. Prior to the announcement of Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, she had acted as the first lady of the court.

A prestigious marriage was arranged for her to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, who was many years her senior. She had no children by him and survived him by many years. After Charles’ death, Margaret maintained a close friendship with her Charles’ only daughter Mary. The respect in which she was held in her adopted country enabled her to play an active supporting role for the Yorkist cause on many occasions. After the death of her brother Richard III, she continued her efforts, backing both Lambert Simnel and later Perkin Warbeck. She died at Malines and is buried in the church of Cordéliers.

The arms of Burgundy, shown impaling France modern and England quarterly on her arms were: Quarterly, first and fourth, azure, three fleurs de lys or within a bordure gobony argent and gules; second, per pale, Bendy of six or and azure within a bordure gules and sable, a lion rampant or; third, per pale, Bendy of six or and azure, within a bordure gules and argent, a lion rampant gules crowned or; over all an inescutcheon, or, a lion rampant sable.

George of York, Duke of Clarence, 1449–1478

Born in Dublin, George was the sixth son of Richard, Duke of York, and Cicely Neville. He was created Duke of Clarence in the first year of Edward IV’sreign. Until Elizabeth Woodville finally bore Edward a son in 1470, Clarence was the heir presumptive ,and it was soon clear to the Earl of Warwick that he was discontented and ambitious. On 11 July 1469, George married Isobel Neville, Warwick’s elder daughter, against the wishes of his brother, cementing an alliance against the king. When Warwick reconciled with Margaret of Anjou, however, and his younger daughter, Anne, was betrothed to the Lancastrian heir, George realized that he was not to be made king in Edward’s place. At the last minute, he returned to the Yorkist fold and was reconciled with Edward and his younger brother Richard. After Warwick’s death at the Battle of Barnet in 1471, George laid claim to his vast estates, and although eventually forced to share them when Richard of Gloucester married the now-widowed Anne Neville, he remained a rich and powerful prince. He continued to flout Edward’s authority, however, and was put in the Tower. In 1478 a Bill of Attainder passed the death sentence on Clarence and he died in the Tower, the exact manner of his death being unknown. Clarence and Isobel had four children, of whom two, Margaret and Edward, survived.

Clarence’s arms were: Quarterly, France modern and England, over all a label of three points argent each charged with a canton gules; his crest was On a chapeau gules turned up ermine, a lion statant guardant crowned or, charged on the breast with a label as in the arms; his badges were A bull passant sable armed unguled and membered or, gorged with a label of three points argent each charged with a canton gules, and A silver gorget of chain, edged and clasped with gold and lined with red.

Margaret Plantagenet, Countess of Salisbury, 1473–1541

Margaret was the eldest child of George, Duke of Clarence and Isobel Neville, she married Sir Richard Pole, K.G. in 1491. They had four sons and a daughter. During the fifth year of the reign of Henry VIII, Margaret, as heiress to the titles of Warwick and Salisbury, petitioned the king and was restored to the title of Countess of Salisbury. She was appointed governess to the Princess Mary and remained in favor until Anne Boleyn became the Queen. Her loyalty to Princess Mary caused her to be dismissed from court.

After the downfall of Anne Boleyn, Margaret returned to court. She did not remain in favor for long. Because of the letter her son, Cardinal Reginal Pole, wrote to the King, and of the betrayal of her son Geoffrey, the Countess was arrested and put into the Tower in March 1539. She was kept in the Tower under close confinement for two years and was executed without trial. She was beatified by the Roman Catholic Church in 1886.

Her arms were: Quarterly, first, Quarterly, France modern and England, a label of three points argent each charged with a canton gules; second, gules, a saltire argent, a label of three points gobony argent and azure impaling Gules, a fess between six crosses crosslet or; third, Chequy or and azure, a chevron ermine impaling Argent, three lozenges conjoined in fess gules; fourth, Or, an eagle displayed vert impaling Quarterly, I and IV, Or, three chevrons gules; II and III, Quarterly, Argent, and gules, a fret or, overall a bendlet sable.

Henry Pole, Lord Montagu, 1492–1539

The eldest son of Margaret Plantagenet, he was knighted by Henry VIII in 1513 during Henry’s French campaign. He was a ember of the royal household and was allowed his own livery. In 1520, he attended Henry VIII at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. He was one of the peers who convicted Anne Boleyn.

As a Roman Catholic, Pole did not approve of Henry’s destroying Church property and the anti-Catholic feeling in England. Henry was fully of Montagu’s feelings, and through his betrayal of his brother Geoffrey Pole, the king now had the evidence he needed to have Montagu arrested in put into the Tower. Pole was tried and found guilty by a jury of his peers. He went to the block on December 9 1539.

He married Jane, daughter of George Neville, Lord Bergavenny, in 1513. They had three children. His only son may have been attainted with his father and died in the Tower.

Geoffrey Pole, 1502?-1558

The second son of Margaret Plantagenet, little is known of his early life. In 1529, he was knighted by Henry VIII at York Place. A devout Roman Catholic, he greatly disapproved of Henry VIII’s divorce proceedings from Katherine of Aragon. Although he was appointeed one of the servitors at Anne Boleyn’s coronation, his loyalties were with Princess Mary and the former Queen Katherine. He then visited the imprial ambassador Chapuys and assured him that if the Holy Roman Emperor were to invade England to redress the wrong that had been done to Queen Katherine, that the English people would favor him.

Unfortunately, his words reached the ears of the king and he was arrested and sent to the Tower on August 1538. He was persuaded to talk and he revelaed the names of secret Papists at court, including his own brother, Henry Lord Montagu. Geoffrey was pardoned as a result of his betrayal and the others he mention, including his brother, were executed.

Having felt guilty at betraying his brother and friends, Geoffrey tried to commit suicide while he was in the Tower. In 1540, he left his family behind and fled to Europe, where he remained until the reign of Queen Mary. He returned to England and died in 1558.

He married Constance, the elder of two daughter and heirs of Sir John Pakenham. They had five sons and six daughters.

Arthur Pole, 1502-1535

Third son of Margaret Plantagenet, he was sentenced to death in the reign of Elizabeth I, being implicated in a plot to release Mary, Queen of Scots. Because of his royal blood, the Queen spared him from execution but not imprisonment.

In 1526, he married Jane Lewknor. It is not known if there were any children from this marriage.

Reginald Pole, 1500-1558

The youngest son of Margaret Plantagenet, he graduated from Magdelan College, Oxford. He was sent to Italy to complete his education and lived there for five years. Reginald was another Pole family member who did not approve of Henry’s divorce from Queen katherine. The King was well aware of this and several times tried to get Pole on his side. At the urging of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Pole wrote Henry a letter, in which he attacked Henry’s policy of royal supremacy and defended the spiritual authority of the Pope. It was at this time that he was created a cardinal by Pope Paul III. Henry then put a price on the new cardinal’s head and arrested and executed many members of the pole family, including his mother and his oldest brother Henry Lord Montagu.

When Henry’s daughter Mary became Queen, he was commission as a papal Legate. He landed in England in 1554 and began to reorganize the country back into the Church of Rome. Two years later he was ordained as a priest and the following year became the Archbishop of Canterbury.

For the next two years, Cardinal Pole help Queen Mary with her persecution of English Protestants. Disapproving of Pole’s methods, Pope Paul IV cancelled his legatine authority and denounced him as a heretic. Shortly afterwards, he fell ill and died twelve hours after Queen Mary on November 17 1558.

Ursula Pole, ? -1570

Ursula was the only daughter of Margaret Plantagenet. In 1518, she married Henry Stafford, first Baron Stafford. Very little is known of her. It is believed that she had at least thrteen children before her death in 1570.

Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick, 1474–1499

The son of George, Duke of Clarence, and Isobel Neville, he may have suffered from some form of mental impairment. He lived in the royal apartments in the Tower under the reign of his uncle Richard III. Henry VII kept him in the Tower, but as a prisoner. When Perkin Warbeck was imprisoned in the Tower, the two attempted to escape (possibly at the instigation of Henry’s agents) and both were executed in 1499.

Edward IV, King of England, 1442–1483

By the Grace of God, King of England and France and Lord of Ireland

The eldest son of Richard, Duke of York and Cecily Neville, Edward was born in Rouen, France, on April 28, 1442. He was educated at Ludlow Castle, along with his younger brother Edmund, Earl of Rutland. He inherited the title of Earl of March. Edward. was raising forces in the Welsh borders for the Yorkist cause when his father and younger brother Edmund were killed at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460. Acting speedily and decisively, Edward routed the Lancastrians at the battles of Mortimer’s Cross and Towton, and claimed the throne. Henry VI was then acclaimed a usurper and a traitor. Edward was crowned in June 1461. He was an extremely popular ruler, although well-known for his licentious behaviour. During his reign, printing and silk manufacturing were introduced into England.

Edward’s secret marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, a widow of a Lancastrian knight, angeed the old nobility and alienated his cousin Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (also known as "The Kingmaker"), who had previously been a major power during the early days of Edward’s reign. In 1469, Edward was deposed by Warwick, and was drien out of England and to Burgundy. Warwick reinstated Henry VI. Two years later, backed by his brother-in-law, Charles ("The Bold"), Duke of Burgundy, returned to England with a large army and defeated the Lancastrians at the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury.

The remaining years of his reign were, for the most part, peaceful. There was, however, a short war with France in 1475, after which Louis XI agreed to pay Edward a yearly subsidy. Edward died on April 8 1483 and was buried at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor.

As King, Edward’s arms were: Quarterly, France modern and England, and his crest On a chapeau gules turned up ermine, a lion statant guardant crowned or. As badges, he used the white rose of York, the sun in splendour, and the white rose en soliel, as well as the lion, the bull and the hart, the falcon and fetterlock of the dukes of York, and a white rose incorporating red petals, a forerunner of the Tudor rose.

Elizabeth Woodville, 1437–1492, Queen of England

Elizabeth was the eldest child of Sir Richard Woodville and Jacquetta of Luxembourg. She was maid of honor to Margaret of Anjou. She was married to Sir John Grey of Groby, who was killed in battle in 1461, leaving her with two small sons. Elizabeth married Edward IV secretly in April 1464 and was crowned Queen in May 1465. She was also a patroness of Queens’ College, Cambridge and gave the College its first Statues in 1475. Her ten brothers and sisters, who were as avaricious and unpopular as herself, were raised to high rank by the king. Elizabeth and Edward had three sons and seven daughters.

Following her husband’s death in 1483, their marriage was declared invalid by Parliament and their children illegitimate. In 1485, however, Elizabeth’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York, married Henry VII and became Queen of England. Elizabeth Woodville was subsequently banished to Bermondsey Abbey, where she died in 1492.

Elizabeth Woodville’s seal displayed a shield of her husband’s arms impaling her own, which were Quartlerly, first argent, a lion rampant double queued gules, crowned or (Luxemburg, her mother’s family), second quarterly, I and IV, gules a star if eight points argent; II and III, azure, semée of fleurs de lys or; third, barry argent and azure, overall a lion rampant gules; fourth, gules, three bendlets argent, on a chief of the first, charged with a fillet in base or, a rose of the second; fifth, three pallets vairy, on a chief or a label of five points azure, and sixth, a fess and a canton conjoined gules (Woodville).

Children of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville

Elizabeth of York, 1466–1503, Queen of England

Born 11 February, 1466 at Westminster Palace, Elizabeth was the first born child of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was betrothed to George Neville, Duke of Bedford, and then engaged to the Charles, the Dauphin of France (later Charles VIII). Elizabeth married Henry Tudor in 1486 and became Queen of England, thus uniting the Houses of York and Lancaster. As. Queen, she was completely dominated by Henry VII and his mother Margaret Beaufort.

She bore Henry eight children: (1) Arthur, Prince of Wales, b. 1486; (2) Margaret (later Queen of Scotland) b. 1489; (3) Henry (later Henry VII) b. 1491; (4) Elizabeth b.1492; (5) Mary (later Queen of France and Duchess of Suffolk) b. 1496; (6) Edmund (died young) 1499; (7) Edward (died young); and (8) Katherine (died young) b. 1503. Elizabeth died in childbirth in on her birthday in 1503, at the age of 37 years. She is buried beside her husband in the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey.

Mary of York, 1467-1482

Mary was the second daughter, born 11 August, 1467 at Windsor Castle. She was promised in marriage to the King of Denmark, but died in 1482 before the marriage could take place. She is buried in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor.

Cicely of York, 1469–1507, Viscountess Welles

Cicely was born on 20 March 1469 at Westminster Palace. She was originally promised in a marriage treaty to the heir of James III of Scotland but instead married John, Lord Welles, by whom she had two daughters Elizabeth and Anne, both of whom died without issue. By her second marriage, to Thomas Kyme of Isle of Wight, she had Richard and Margaret. She died at Quarr Abbey, Isle of Wight on 24 August 1507.

Edward V, 1470–?

The eldest son of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, Edward was born in sanctuary at Westminster on 4 November 1470. He was created Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall, Earl of Chester, March and Pembroke. As Prince of wales, Edward was educated at Ludlow Castle by his uncle Anthony, Earl Rivers.

Following his father’s death, he was brought to London to be crowned. Parliament, however, declared him to be illegitimate and Richard of Gloucester became king. Edward and his brother Richard lived in the Tower of London during the summer of 1483. Their fate is unknown.

Edward’s arms as king were: Quarterly, France modern and England, and his crest on his Great Seal; on a chapeau gules turned up ermine encircled by a royal coronet, a lion statant guardant crowned or.

Margaret of York, b. and d. 1472

This child of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville (not to be confused with her aunt of the same name) was born 10 April 1472 at Windsor Castle and died on 11 December of the same year. She is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Richard, Duke of York, 1473–?

Born at Shrewsbury, the second son of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, Richard was created Duke of York in 1474. In 1478, at the age of four years, Richard was married to six-year-old Anne Mowbray, who had inherited the estates of her father John Lord Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk in 1475. They married at St Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster, but Anne Mowbray died while still a child. When his brother, Edward V, was deposed, young Richard, who had been in sanctuary with his mother, was taken by the Archbishop of Canterbury to live with his brother in the Royal Apartments in the Tower of London. Their fate remains a mystery, but many contemporary heads of state including (in secret correspondance, but not publicly) the Spanish King and Queen, believed the claimant Perkin Warbeck, executed by Henry VII, to be Richard.

His arms were: Quarterly, France modern and England, a label of three points, argent on the first point a canton gules; his crest was On a chapeau gules turned up ermine, a lion statant guardant crowned or, gorged with a label as in the arms, and his badge a falcon volant argent, membered or, within a fetterlock unlocked gold.

George of York, Duke of Bedford, 1477-1479

The seventh child and third youngest son of Edward IV and Eizabeth Woodville, he was created Duke of Bedford, but died very young. He is buried at Windsor.

Anne of York, 1475-1510

Anne was married to Thomas Howard, third Duke of Norfolk. She died in 1510 without surviving issue.

Catherine of York, 1479–1527

The sixth daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, Catherine married William Courtenay, Earl of Devon, and had one child, Henry, who succeeded his father as Earl. Despite being made Marquis of Exeter, Henry’s Yorkist blood doomed him, and he was beheaded in 1538 for being implicated in a plot with Cardinal Pole. Henry’s only son, Edward Courtenay, died without issue, and the descendants of this family are from the younger brother of an earlier generation.

The arms of Catherine were her husband’s arms impaling her own: Quarterly, first and fourth, or, three torteaux; second and third, or a lion rampant azure; impaling quarterly, first, quarterly, France modern and England, second and third, de Burgh, and fourth Mortimer.

The arms of Henry Courtenay were: Quarterly, first, France and England quarterly, within a bordure quarterly of England and France, second and third, or, three torteaux; fourth, or a lion rampant azure,; and his crest, out of a ducal coronet or, a plume of ostrich feathers four and three argent.

Bridget of York, 1480-1513

The tenth and last child of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, she became a nun at Dartford and died in 1513.

Richard III 1452–1485

By the Grace of God, King of England and France and Lord of Ireland

Richard III was born on the 2October, 1452 in Fotheringhay Castle during the tumultuous period known as the Wars of the Roses. His personal motto of Loyaulte Me Lie was a testament of his unswerving loyalty for his brother, Edward IV.

In 1461, he was sent to Middleham Castle to begin his knightly training under his cousin, Richard Neville, known as "The Kingmaker". In 1472, he married the Lady Anne Neville and they retired to Middleham. As Lord of the North, Richard spent the next twelve years bringing peace and order to an otherwise troublesome area of England. Through his hard work and diligence, he attracted the loyalty and trust of the northern gentry. His fairmindedness and justice became his byword. He had a good working reputation of the law, was an able administrator and was militarily formidable. Under his leadership, he won a brilliant campaign against the Scots that is diminished by our lack of understanding of the region in his times.

He enjoyed a special relationship with the city of York and intervened on its behalf on many occasions. Richard, known to be a pious man, was instrumental in setting up no less than ten chantries and procured two licenses to establish two colleges; one at Barnard Castle in County Durham and the other at Middleham in Yorkshire. It is known that his favorite castle was Middleham and he was especially generous to the church raising it to the status of collegiate college. The statutes, written in English rather than Latin, were drawn up under his supervision.

With the untimely death of his brother, Edward IV in 1483, he was petitioned by the Lords and Commons of Parliament to accept the kingship of England. During his brief reign, he passed the most enlightened laws on record for the Fifteenth Century. He set up a council of advisors that diplomatically included Lancastrian supporters, administered justice for the poor as well as the rich, established a series of posting stations for royal messengers between the North and London. He fostered the importation of books, commanded laws be written in English instead of Latin so the common people could understand their own laws. He outlawed benevolences, started the system of bail and stopped the intimidation of juries. He re-established the Council of the North in July of 1484 and it lasted for more than a century and a half. He established the College of Arms that still exists today. He donated money for the completion of St. George's Chapel at Windsor and King's College in Cambridge. He modernized Barnard Castle, built the great hall at Middleham and the great hall at Sudeley Castle. He undertook extensive work at Windsor Castle and ordered the renovation of apartments at one of the towers at Nottingham Castle.

In 1484, while Richard and Anne were at Nottingham, they received word that their beloved son, Edward, who was at Middleham, died suddenly after a brief illness. His wife, Anne, never recovered from the loss of her son and died almost a year later. Her body was borne to Westminster Abbey and laid to rest on the south side of St. Edward's Chapel. Richard wept openly at her funeral and later shut himself off for three days.

In eighteen months, he lost brother, son and spouse. Throughout these tragedies, he remained steadfast to his obligations. His reign showed great promise, but amidst the intrigues and power struggles of his time, he found himself on Bosworth Field. Richard III was 32 years old when he died at the Battle of Bosworth and was the last English king to die in battle.

Arms as Duke of Gloucester: France and England modern, over all a 3-pointed label ermine, on each point a conton gules.

Arms: Quarterly, France modern and England, and his crest on his Great Seal; on a chapeau gules turned up ermine encircled by a royal coronet, a lion statant guardant crowned or; special cognisant, a boar rampant argent, armed and bristled or.

Anne Neville, Queen of England, 1456-1485

Anne Neville was born on 11 June 1456 at Warwick Castle, the younger daughter of Richard Warwick ("The King Maker") and Anne Beauchamp, heiress to the large Beauchamp estate. She spent her childhhod at warwick Castle along with her older sister Isabel. In 1469, her father, no longer in favor with Edward IV, fled to Calais, bringing his family with him. Shortly afterwards, Warwick went over to the Lancastrians, and Anne was betrothed to the Lancastrian Prince Edward, Prince of Wales. Her father and uuncle John were killed at Barnet in April 1471. Edward of Lancaster died at Tewkesbury a month later. She married Richard, Duke of Gloucester and they spent most of their married life at Middleham Castle. They had only one living child, Edward, Prince of Wales. In 1484, Prince Edward died. Anne never recovered and died, probably of tuberculosis, in March 1485, just five months before her husband Richard.

Her arms were: Quarterly, France modern and England, impaling gules, a saltire argent.

Edward, Prince of Wales, Earl of Chester and Salisbury, 1473–1484

Edward was the only surviving child of Richard III and Queen Anne. He was born at Middleham Castle, Yorkshire and was created Prince of Wales during the first year of his father’s reign. Edward suddenly became ill with abdominal pain in 1484 and quickly died, possibly of appendicitis. His parents were distraught with grief and his death may have hastened Anne’s decline.

Arms: Quarterly, France modern and England, a label of three points argent.

John of Gloucester

John was Richard III’s illegitimate son. His mother is unknown. He was also called John of Pomfret, his father appointed him Captain of Calais in 1485, calling him ‘our dear son’. After his father’s death, during the reign of Henry VII, John was beheaded on the pretext of treasonable activities in Ireland.

Lady Catherine Plantagenet

Katherine was the illegitimate daughter of Richard III. Her mother is unknown. In 1484, Katherine was married to William Herbert, Earl of Huntingdon. Richard settled property worth 1,000 marks a year on the couple. Katherine died young without producing any living children.

Some concrete facts about kings which had come frjm The House of York

Edward IV  (1461-70, 1471-83 AD)

(1461-70, 1471-83 AD)

![]() Edward IV, son of Richard, Duke of York and Cicely Neville, was born in 1442. He married Elizabeth Woodville in 1464, the widow of the Lancastrian Sir John Grey, who bore him ten children. He also entertained many mistresses and had at least one illegitimate son.

Edward IV, son of Richard, Duke of York and Cicely Neville, was born in 1442. He married Elizabeth Woodville in 1464, the widow of the Lancastrian Sir John Grey, who bore him ten children. He also entertained many mistresses and had at least one illegitimate son.

Edward came to the throne through the efforts of his father; as Henry VI became increasingly less effective, Richard pressed the claim of the York family but was killed before he could ascend the throne: Edward deposed his cousin Henry after defeating the Lancastrians at Mortimer's Cross in 1461. Richard Neville, the Kingmaker, Earl of Warwick proclaimed Henry king once again in 1470, but less than a year elapsed when Edward reclaimed the crown and had Henry executed in 1471.

The rest of his reign was fairly uneventful. He revived the English claim to the French throne and invaded the weakened France, extorting a non-aggression treaty from Louis XI in 1475 which amounted to a lump payment of 75,000 crowns, and an annuity of 20,000. Edward had his brother, George, Duke of Clarendon, judicially murdered in 1478 on a charge of treason. His marriage to Elizabeth Woodville vexed his councilors, and he allowed many of the great nobles (such as his brother Richard) to build uncharacteristically large power bases in the provinces in return for their support.

Edward died suddenly in 1483, leaving behind two sons aged twelve and nine, five daughters, and a troubled legacy.

Edward began his reign in 1461 and ruled for eight years before Henry's brief return. His reign is marked by two distinct periods, the first in which he was chiefly engaged in suppressing the opposition to his throne, and the second in which he enjoyed a period of relative peace and security. Both periods were marked also by his extreme licentiousness; it is said that his sexual excesses were the cause of his death (it may have been typhoid), but he was praised highly for his military skills and his charming personality. When Edward married Elizabeth Woodville, a commoner of great beauty, but regarded as an unfit bride for a king, even Warwick turned against him. We can understand Warwick's switch to Margaret and to Edward's young brother, the Duke of Clarence, when we learn that he had hoped the king would marry one of his own daughters.

Clarence continued his activities against his brother during the second phase of Edward's reign; his involvement in a plot to depose the king got him banished to the Tower where he mysteriously died (drowned in his bath). Edward had meanwhile set up a council with extensive judicial and military powers to deal with Wales and to govern the Marches. His brother, the Duke of Gloucester headed a council in the north. He levied few subsidies, invested his own considerable fortune in improving trade; freed himself from involvement in France by accepting a pension from the French King; and all in all, remained a popular monarch. He left two sons, Edward and Richard, in the protection of Richard of Gloucester, with the results that have forever blackened their guardian's name in English history.

Edward V (1483 AD)

Edward V, eldest son of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, was born in 1470. He ascended the throne upon his father's death in April 1483, but reigned only two months before being deposed by his uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester. The entire episode is still shrouded in mystery. The Duke had Edward and his younger brother, Richard, imprisoned in the Tower and declared illegitimate and named himself rightful heir to the crown. The two young boys never emerged from the Tower, apparently murdered by, or at least on the orders of, their Uncle Richard. During renovations to the Tower in 1674, the skeletons of two children were found, possibly the murdered boys.

Richard III (1483-85)

![]() Richard III, the eleventh child of Richard, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, was born in 1452. He was created third Duke of Gloucester at the coronation of his brother, Edward IV. Richard had three children: one each of an illegitimate son and daughter, and one son by his first wife, Anne Neville, widow of Henry IV's son Edward.

Richard III, the eleventh child of Richard, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, was born in 1452. He was created third Duke of Gloucester at the coronation of his brother, Edward IV. Richard had three children: one each of an illegitimate son and daughter, and one son by his first wife, Anne Neville, widow of Henry IV's son Edward.

Richard's reign gained an importance out of proportion to its length. He was the last of the Plantagenet dynasty, which had ruled England since 1154; he was the last English king to die on the battlefield; his death in 1485 is generally accepted between the medieval and modern ages in England; and he is credited with the responsibility for several murders: Henry VI , Henry's son Edward, his brother Clarence, and his nephews Edward and Richard.

Richard's power was immense, and upon the death of Edward IV , he positioned himself to seize the throne from the young Edward V . He feared a continuance of internal feuding should Edward V, under the influence of his mother's Woodville relatives, remain on the throne (most of this feared conflict would have undoubtedly come from Richard). The old nobility, also fearful of a strengthened Woodville clan, assembled and declared the succession of Edward V as illegal, due to weak evidence suggesting that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was bigamous, thereby rendering his sons illegitimate and ineligible as heirs to the crown. Edward V and his younger brother, Richard of York, were imprisoned in the Tower of London, never to again emerge alive. Richard of Gloucester was crowned Richard III on July 6, 1483.

Four months into his reign he crushed a rebellion led by his former assistant Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, who sought the installation of Henry Tudor , a diluted Lancaster, to the throne. The rebellion was crushed, but Tudor gathered troops and attacked Richard's forces on August 22, 1485, at the battle of Bosworth Field. The last major battle of the Wars of the Roses, Bosworth Field became the death place of Richard III. Historians have been noticeably unkind to Richard, based on purely circumstantial evidence; Shakespeare portrays him as a complete monster in his play, Richard III. One thing is for certain, however: Richard's defeat and the cessation of the Wars of the Roses allowed the stability England required to heal, consolidate, and push into the modern era.

Richard of Gloucester had grown rich and powerful during the reign of his brother Edward IV, who had rewarded his loyalty with many northern estates bordering the city of York. Edward had allowed Richard to govern that part of the country, where he was known as "Lord of the North." The new king was a minor and England was divided over whether Richard should govern as Protector or merely as chief member of a Council. There were also fears that he may use his influence to avenge the death of his brother Clarence at the hands of the Queen's supporters. And Richard was supported by the powerful Duke of Buckingham, who had married into the Woodville family against his will.

Richard's competence and military ability was a threat to the throne and the legitimate heir Edward V. After a series of skirmishes with the forces of the widowed queen, anxious to restore her influence in the north, Richard had the young prince of Wales placed in the Tower. He was never seen again though his uncle kept up the pretence that Edward would be safely guarded until his upcoming coronation. The queen herself took sanctuary in Westminster Abbey, but Richard had her brother and father killed.

Edward's coronation was set for June, 1483. Richard planned his coup. First he divided the ruling Council, convincing his own followers of the need to have Lord Hastings executed for treason. (It had been Hastings who had informed him of the late King's death and the ambitions of the Queen's party). He then had his other young nephew Richard join Edward in the Tower. One day after that set for Edward's coronation, Richard was able to pressure the assembled Lords and Commons in Parliament to petition him to assume the kingship. After his immediate acceptance, he then rode to Westminster and was duly crowned as Richard III. His rivals had been defeated and the prospects for a long, stable reign looked promising. Then it all unraveled for the treacherous King.

It is one thing to kill a rival in battle but it is another matter to have your brother's children put to death. By being suspected of this evil deed, Richard condemned himself. Though the new king busied himself granting amnesty and largesse to all and sundry, he could never cleanse himself of the suspicion surrounding the murder of the young princes. He had his own son Edward invested as Prince of Wales, and thus heir to his throne, but revulsion soon set in to destroy what, for all intents and purposes, could have been a well-managed, competent royal administration.

It didn't help Richard much that even before he took the throne he had denounced the Queen "and her blood adherents," impugned the legitimacy of his own brother and his young nephews and stigmatized Henry Tudor's royal blood as bastard. The rebellion against him started with the defection of the Duke of Buckingham whose open support of the Lancastrian claimant overseas, Henry Tudor, transformed a situation which had previously favored Richard.

The king was defeated and killed at Bosworth Field in 1485, a battle that was as momentous for the future of England as had been Hastings in 1066. The battle ended the Wars of the Roses, and for all intents and purposes, the victory of Henry Tudor and his accession to the throne conveniently marks the end of the medieval and the beginning of England's modern period.

Sources:

1. www.britannia.com\history

2. www.numizmat.net

3. http://reference.allrefer.com/encyclopedia/Y/York-hou.html

4. http://www.britannia.com/history/monarchs

5. www.hotbot.com

6. www.yahoo.com

Ïîõîæèå ðàáîòû

... «Ðóñè÷». Ñìîëåíñê. 2001. 3. Îôèöèàëüíûé ñàéò Áóêèíãåìñêîãî äâîðöà: www.royal.gov.uk. 4. Ñàéò, ïîñâÿùåííûé èñòðèè êîðîëåâñêèõ äèíàñòèé ìèðà: www.royalty.nu. EXTRACT «The house of Tudor» INTRODUCTION. I decided to write this essay, because, I am really interested in English history. The five sovereigns of the Tudor dynasty are among the most well ...

... of the aristocracy was killed (some noble families even disappeared) and the royal dynasty changed. It has also been a vast source of inspiration for English authors, such as Shakespeare. The history of the war of the two Roses is really propitious to literary narration : you have a Queen with a strong personality (Marguerite), a mad King, traitors, multiple reversal of situation, ... But the ...

... Warwick would have been able to count on thousands of men scattered over no fewer than 20 shires. Note the predominance of archers. The contemporary Paston letters give a good idea of the value of the longbowman during the Wars of the Roses. When Sir John Paston was about to depart for Calais, he asked his brother to try to recruit four archers for him: 'Likely men and fair conditioned and good ...

... all that wonderful things in America might be interesting to discover something new, where the tourists are not so common and whereyou can meet only native sitizens, but they are also the sights of USA. Highway 395 Out where the Sierras drop straight down into the sagebrush of eastern California's Owens Valley, truckers, hunters and road-trippers cruise Hwy 395. Though the road runs several ...

0 êîììåíòàðèåâ