Навигация

Choosing Work According to the Curriculum

2. Choosing Work According to the Curriculum

Assessment of students' knowledge and abilities is the teacher's absolutely best educational tool. It is so powerful because it is an inspiration to the teacher's creativity. When the teacher sees where students' educational needs lie, his or her mind begins to work on what to do about them. An analogy with a politician is in order: the politician who goes out to meet and talk with the people learns what the needs are and then thinks up strategies for meeting them; the politician who lacks the common touch, on the other hand, generates ideas that are often inappropriate. Similarly, the teacher who assesses students' knowledge and abilities begins to think out appropriate educational strategies, whereas, with the ivory tower teacher, there is often a mismatch between what is taught and what is appropriate for the students. When tests are administered in advance of teaching, the teacher sees where the needs lie, and the students realize that there is much to learn - the test results are an inspiration to student humility.

Assessment helps prevent the teacher from teaching over the heads of the students. When the teacher knows that a student is unsure about step 1, there is no point in going on to step 2. For example, if a student doesn't understand subject and predicate, there is no point in teaching sentence diagramming; if a student can't multiply or subtract, there is no point in teaching long division.

Many classroom tests come from textbooks. Math textbooks provide many tests, as do some basal reading series.

Some of the best assessments are the simplest. For example, a teacher's dictating a paragraph, where the students are required to write down what is dictated, is very simple but very effective. Finding a paragraph to dictate is no problem, and student shortcomings in spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and handwriting are immediately apparent to the teacher[3].

In addition to assessing students' knowledge and attitudes before a study begins, many teachers assess students' interests as the study progresses. They recognize individual differences among students and make room in a study for students to go off on their own in some area. For example, in a study of Rome students might be asked to express interest in pursuing knowledge of Roman authors, Roman warriors, Roman law, Roman architecture, Roman cities, or Roman colonies, among other topics. Students would then go off on their own and come up with a true-false test or a short report on their topic to share with the class.

The content of most classroom assessment is specific to the curriculum of the grade or class being taught. For example, if a unit is to be taught on Rome, the teacher will make a list of the vocabulary words to be taught in the unit, geography concepts, famous Romans, wars, and so on, and will then test the students on their knowledge. The answers are usually open-ended: who was Tacitus? Who was Cicero? What is the name of the sea east of Italy? The results tell the teacher - and the students - what the students don't know; implied in the results are what the students need to know. Teacher and students are then ready to embark on the study.

There are knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are the responsibility of all teachers and all students, and the teacher will do well to assess this knowledge and these skills and attitudes. There was a time in American education when a high school social studies teacher, for example, would say that the teaching of punctuation and capitalization was the responsibility of the English teacher, not the social studies teacher. The team approach in secondary schools has done away with this compartmentalization, so that now during team meetings teachers cooperatively discuss educational needs and then plan strategies to meet them.

Similarly, all teachers take responsibility for students' being able to speak correctly, to write good English, to expand vocabulary, to add and subtract, to observe good health habits, to be safe, to have good attitudes toward school, and to learn about current events. The day of sending a student back a grade to learn something is, for the most part, a thing of the past.

Therefore, in addition to teachers' assessing students' knowledge of specific grade level curriculum or subject matter,it comes within the purview of most teachers to assess students' English proficiency, understandings about health and safety, attitudes toward school, and knowledge of current events. Students come to see how much there is to learn and share in developing educational strategies.

4. Keeping a Studious Classroom

Over the door in one studious classroom is a sign reading, "Quiet, please. Learning underway." Another classroom has a poster that says, "You are here to work." All the students not with the teacher are working independently. One student is writing an unknown word on the whiteboard, where the heading reads, "New vocabulary words." Later, the class will discuss the word, and each student will enter the word with its meaning in a notebook. On a corner of the whiteboard are the assignments for the day; separately, there are the assignments for the week - "Write one half page on your pet." "Find information (no more than half a page) on Apaches." "Write a number problem requiring division for the class to solve." "Look through the dictionary for a spelling word ending in 'tion'." Students are busily engaged in completing these assignments. Several students are finding information on Apaches, a current class topic; one student is using an encyclopedia; another is in the Internet. The student in the Internet has found some resources to write away for. Other students are working on worksheets and work from kits.

The teacher is not harassed. Students in this classroom are eager to produce and to have their work checked and sometimes expect more of the teacher than one person can do; consequently, the teacher limits his or her commitment: weekly written assignments must be no more than a page, monthly reports must be no more than two pages, etc.

Discipline in the studious classroom is a matter, first, of convincing the students of their ignorance. When a student misbehaves, the teacher calls out, "Who was the fourth president of the United States?" If the student answers, "James Madison," the teacher calls out, "What is the capital of Hungary?" The wrong answer is followed by a short lecture on how much the student has to learn and how short is the time for learning. Students in this classroom are not time wasters because they realize how much there is to learn.

Discipline in the studious classroom is also a matter of liking to learn. Students are convinced not only of their ignorance but also of the desirability of overcoming it. They diligently write vocabulary and spelling words in their notebooks. They use the dictionary, the encyclopedia, and other reference books. Each student keeps a notebook of half-page comments about books read.

Much teacher time is spent at the teacher's desk with a student. The teacher reads and corrects written assignments with the student. Math assignments are checked individually. Workbook pages are corrected. Since the teacher's time is valuable, work with any one student is limited to a few minutes; however, a few minutes devoted to overcoming a student's specific weaknesses or mistakes can be more valuable than much full-class instruction.

This is not to say that full-class instruction does not exist in the studious classroom. The teacher introduces new topics, explains principles and rules, such as in spoken and written language or math, and hears student reports. However, in general the students are working on their own.

At one time in the development of schooling it was thought that students should be generally social. Since many students would rather talk than learn, the consequence of a social classroom was much talk and little learning. Students have plenty of time for socializing outside of the classroom. The purpose of being in school is to learn. A poster in a classroom says, "There is a place for socializing. This is not it." Fortunately, learning can be interesting, and students who would rather talk can become absorbed in their work. Although being a student in the studious classroom is work, the rewards of this work are great.

Periodically, the teacher meets with each student to evaluate progress and to make decisions about appropriate learning materials. Because of limitations on the teacher's time, plans for work to be accomplished must cover at least a month. A student placed in a workbook or a kit works in that workbook or kit over a period of time. One criterion in selecting a workbook or kit is, how suitable is it for long-term use.

Students who lack commitment to their independent work find many ways to avoid it - horseplay with the student in the next seat, finding excuses for leaving the classroom, or bothering the teacher with questions. The committed student, on the other hand, devours more and more knowledge. Basic to the success of independent work is a student's commitment to it.

When a student recognizes his or her own ignorance and sees work as the way to overcome it, commitment grows. If the teacher tests often and tests widely, the teacher can say, you are weak in this area, and here is our plan for overcoming your weakness. The student, seeing his or her own ignorance, has a purpose for doing work. When the student is retested at the end of a period of independent work, he or she can see improvement.

When students are not naturally motivated, there are things that a teacher can do to obtain student commitment. The first question for a teacher to ask is, of course, is this work appropriate and not too difficult. Next, the teacher can give recognition to work accomplished. Putting a sticker on a child's completed work is still a welcomed sign of recognition. A gold star gives recognition on a checklist. An "A" at the top of a paper gives satisfaction (although anything less than an "A" does not). Positive recognition of a student's work, then, is basic to obtaining his or her commitment to it.

Record keeping, also, is basic to student commitment, because the student can see progress in the record. The student in a workbook or kit needs to keep a checklist, most likely in a three-ring binder, listing the work in the workbook or kit and showing checks for work completed. Sometimes, teachers make a wall chart with students' names and work undertaken; however, such a chart, put up for all to see, can be a daunting experience for the slow student, who sees very little on the chart next to his or her name compared with those galloping along.

Похожие работы

... -curricula approaches are encouraged. For language teaching this means that students should have the opportunity to use the knowledge they gain in other subjects in the English class. So we can come to the conclusion that project work activities are very effective for the modern school curricula and should be used while studying. 1.3 Organizing Project Work Although recommendations as to ...

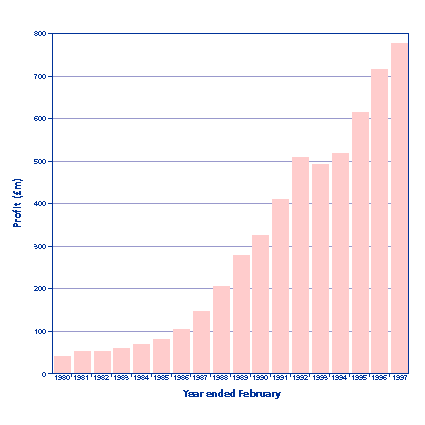

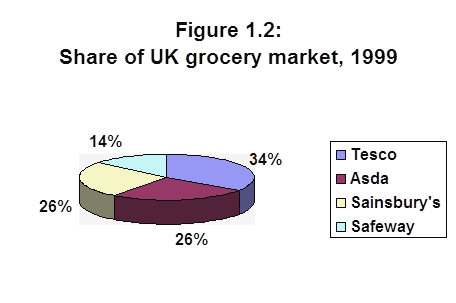

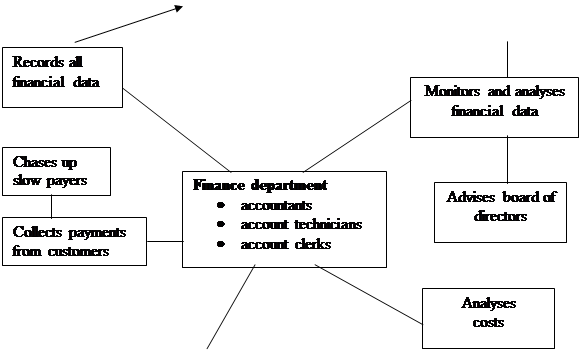

... may allow workers to be flexible when the company needs to change or is having difficulties. · Workers identify with other employees. This may help with aspects of the business such as team work. · It increases the commitment of employees to the company. This may prevent problems such as high labour turnover or industrial relations problems . · It motivates workers in their jobs. ...

... in 1975 together with Paul Alien, his partner in computer language development. While attending Harvard in 1975, Gates together with Alien developed a version of the BASIC computer programming language for the first personal computer. In the early 1980s. Gates led Microsoft's evolution from the developer of computer programming languages to a large computer software company. This transition ...

... like that: what kinds of animals eat grass?» The boy brightened up. «Animals!» he exclaimed, «I thought you said admirals.» Unit 9 Grammar: 1. Passive Voice. 2. Пассивные конструкции характерные для английского языка. 3. Формы инфинитива. I. Language Practice 1. Practise the fluent reading and correct intonation: — Helölo, Tom! — Helølo, Nick ö. Here you ø are at ...

0 комментариев