Навигация

Semantical Characteristics of English Nouns

2. Semantical Characteristics of English Nouns

Nouns fall under two classes: (A) proper nouns; (B) common nouns[2].

a) Proper nouns are individual, names given to separate persons or things. As regards their meaning proper nouns may be personal names (Mary, Peter, Shakespeare), geographical names (Moscow, London, the Caucasus), the names of the months and of the days of the week (February, Monday), names of ships, hotels, clubs, etc.

A large number of nouns now proper were originally common nouns (Brown, Smith, Mason).

Proper nouns may change their meaning and become common nouns:

«George went over to the table and took a sandwich and a glass of champagne. (Aldington)

b) Common nouns are names that can be applied to any individual of ad ass of persons or things (e.g. man, dog, book), collections of similar individuals or things regarded as a single unit (e. g. peasantry, family), materials (e. g. snow, iron, cotton) or abstract notions (e.g. kindness, development).

Thus there are different groups of common nouns: class nouns, collective nouns, nouns of material and abstract nouns.

1. Class nouns denote persons or things belonging to a class. They are countable and have two. numbers: singular and plural. They are generally used with an article.

«Well, sir», said Mrs. Parker, «I wasn't in the shop above a great deal.» (Mansfield)

He goes to the part of the town where the shops are. (Lessing)

2. Collective nouns denote a number or collection of similar individuals or things as a single unit.

Collective nouns fall under the following groups:

(a) nouns used only in the singular and denoting-a number of things collected together and regarded as a single object: foliage, machinery.

It was not restful, that green foliage. (London)

Machinery new to the industry in Australia was introduced for preparing land. (Agricultural Gazette)

(b) nouns which are singular in form though plural in meaning:

police, poultry, cattle, people, gentry They are usually called nouns of multitude. When the subject of the sentence is a noun of multitude the verb used as predicate is in the plural:

I had no idea the police were so devilishly prudent. (Shaw)

Unless cattle are in good condition in calving, milk production will never reach a high level. (Agricultural Gazette)

The weather was warm and the people were sitting at their doors. (Dickens)

(c) nouns that may be both singular and plural: family, crowd, fleet, nation. We can think of a number of crowds, fleets or different nations as well as of a single crowd, fleet, etc.

A small crowd is lined up to see the guests arrive. (Shaw)

Accordingly they were soon afoot, and walking in the direction of the scene of action, towards which crowds of people were already pouring from a variety of quarters. (Dickens)

3. Nouns of material denote material: iron, gold, paper, tea, water. They are uncountable and are generally used without any article.

There was a scent of honey from the lime-trees in flower. (Galsworthy)

There was coffee still in the urn. (Wells)

Nouns of material are used in the plural to denote different sorts of a given material.

… that his senior counted upon him in this enterprise, and had consigned a quantity of select wines to him… (Thackeray)

Nouns of material may turn into class nouns (thus becoming countable) when they come to express an individual object of definite shape.

Compare:

– To the left were clean panes of glass. (Ch. Bronte)

«He came in here,» said the waiter looking at the light through the tumbler, «ordered a glass of this ale.» (Dickens)

But the person in the glass made a face at her, and Miss Moss went out. (Mansfield).

4. Abstract nouns denote some quality, state, action or idea: kindness, sadness, fight. They are usually uncountable, though some of them may be countable.

Therefore when the youngsters saw that mother looked neither frightened nor offended, they gathered new courage. (Dodge)

Accustomed to John Reed's abuse – I never had an idea of plying it. (Ch. Bronte)

It's these people with fixed ideas. (Galsworthy)

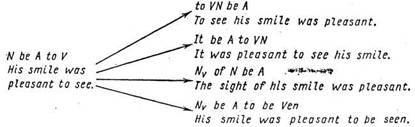

Abstract nouns may change their meaning and become class nouns. This change is marked by the use of the article and of the plural number:

beauty a beauty beauties

sight a sight sights

He was responsive to beauty and here was cause to respond. (London)

She was a beauty. (Dickens)

… but she isn't one of those horrid regular beauties. (Aldington)

3. The Category of Case

The category of case of nouns is the system of opposites (such as girl–girl's in English, дом – дома – дому – дом – домом – (о) доме in Russian) showing the relations of the noun to other words in speech. Case relations reflect the relations of the substances the nouns name to other substances, actions, states, etc. in the world of reality [3]. In the sentence ‘I took John's hat by mistake’ the case of the noun ‘John's’ shows its relation to the noun hat, which is some reflection of the relations between John and his hat in reality.

Case is one of those categories which show the close connection:

(a) between language and speech,

(b) between morphology and syntax.

(a) A case opposite is, like any other opposite, a unit of the language system, but the essential difference between the members of a case opposite is in their combinability in speech. This is particularly clear in a language like Russian with a developed case system. Compare, for instance, the combinability of the nominative case and that of the oblique cases. See also the difference in the combinability of each oblique case: одобрять поступок, не одобрять поступка, удивляться поступку, восхищаться поступком, etc.

We can see here that the difference between the cases is not so much a matter of meaning as a matter of combinability. It can be said that поступок – поступка – поступку, etc. are united paradigmatically in the Russian language on the basis of their syntagmatic differences in speech. Similarly, the members of the case opposite John – John's are united paradigmatically on the basis of their syntagmatic differences.

Naturally, both members of an English noun case opposite have the features of English nouns, including their combinability. Thus, they may be preceded by an article, an adjective, a numeral, a pronoun, etc.

a student…. a student's…

the student…, the student's…

a good student…, a good student's…

his brother…, his brother's…

the two brothers…, the two brothers'…

Yet, the common case grammemes are used in a variety of combinations where the possessive case grammemes do not, as a rule, occur. In the following examples, for instance, John's or boys' can hardly be substituted for John or boys: John saw the boys, The boys were seen by John, It was owing to the boys that…, The boys and he…, etc.

(b) Though case is a morphological category it has a distinct syntactical significance. The common case grammemes fulfil a number of syntactical functions not typical of possessive case grammemes, among them the functions of subject and object. The possessive case noun is for the most part employed as an attribute.

All case opposites are identical in content: they contain two particular meanings, of 'common' case and 'possessive' case, united by the general meaning of the category, that of 'case'. There is not much variety in the form of case opposites either, which distinguishes English from Russian.

An English noun lexeme may contain two case opposites at most (man – man's, men – men's). Some lexemes have but one opposite (England – England's, cattle – cattle's). Many lexemes have no case opposites at all (book, news, foliage),

In the opposite dog – dog's, men – men's, the 'common' case is not marked, i.e. dog and men have zero morphemes of 'common case'. The 'possessive' case is marked by the suffix -'s /-s, – z, – iz/. In the opposite dogs – dogs.' the difference between the opposites is marked only in writing. Otherwise the two opposites do not differ in form. So with regard to each other they are-not marked.

Thus, -'s is the only positive case morpheme of English nouns. It would be no exaggeration to say that the whole category' depends on this morpheme.

As already mentioned, with regard to the category of case English nouns fall under two lexicon-grammatical subclasses: declinable, having case opposites, and indeclinable, having no case opposites.

The subclass of declinable is comparatively limited, including mostly nouns denoting living beings, also time and distance [4].

Indeclinable like book, iron, care have, as a norm, only the potential (or oblique, or lexicon-grammatical) meaning of the common case. But it is sometimes actualized when a case opposite of these words is formed in speech, as in ‘The book's philosophy is old-fashioned’. (The Tribune, Canada).

As usual, variants of one lexeme may belong to different subclasses. Youth meaning 'the state of being young' belongs to the indeclinable. Its variant youth meaning 'a young man' has a case opposite (The youth's candid smile disarmed her. Black and belongs to the declinable.

Since both cases and prepositions show 'relations of substances', some linguists speak of analytical cases in Modern English. To the student is said to be an analytical dative case (equivalent, for instance, to the Russian студенту), of the student is understood as an analytical genitive case (equivalent to студента), by the student as an analytical instrumental case (cf. студентом), etc.

The theory of analytical cases seems to be unconvincing for a number of reasons.

1. In order to treat the combinations of the student, to the student, by the student as analytical words (like shall come or has come) we must regard of, to, with as grammatical word-morphemes [5]. But then they are to be devoid of lexical meaning, which they are not. Like most words a preposition is usually polysynaptic and each meaning is singled out in speech, in a sentence or a word-combination. Cf. to speak of the student, the speech of the student, news of the student, it was kind of the student, what became of the student, etc.

In each case of shows one of its lexical meanings. Therefore it cannot be regarded as a grammatical word-morpheme and the combination of the student cannot be treated as an analytical word.

2. A grammatical category, as known, is represented in opposites comprising a definite number of members. Combinations with different prepositions are too numerous to be interpreted as opposites representing the category of case[6].

The number of cases in English becomes practically unlimited.

3. Analytical words usually form opposites with synthetic ones[7] (comes – came – will come). With prepositional constructions it is different. They are often synonymous with synthetic words.

E. g. the son of my friend = my friend's son; the wall of the garden = the. garden wall.

On the other hand, prepositional constructions can be used side by side with synthetic cases, as in that doll of Mary's, a friend of John's. If we accepted the theory of analytical cases, we should see in of John's a double-case word[8], which would be some rarity in English, there being •'no double-tense words nor double-aspect words and the like [9].

4. There is much subjectivity in the choice of prepositions supposed to form analytical cases[10]. Grammarians usually point out those prepositions whose meanings approximate to the meanings of some cases in other languages or in Old English. But the analogy with other languages or with an older stage of the same language does not prove the existence of a given category in a modern language.

Therefore we think it unjustified to speak of units like to the student, of the student, etc. as of analytical cases. They are combinations of nouns in the common case with prepositions.

The morpheme -'s, on which the category of case of English nouns depends (§ 83), differs in some respects from other grammatical morphemes of the English language and from the case morphemes of other languages.

As emphasized by B.A. Ilyish [11], -'s is no longer a case inflexion in the classical sense of the word. Unlike such classical inflexions, -'s may be attached

a) to adverbs (of substantial origin), as in yesterday's events,

b) to word-groups, as in Mary and John's apartment, our professor of literature's unexpected departure,

c) even to whole clauses, as in the well-worn example the man I saw yesterday's son.

В. A. Ilyish comes to-the conclusion that the -'s morpheme gradually develops into a «form-word»[12], a kind of particle serving to convey the meaning of belonging, possession[13].

G.N. Vorontsova does not recognize –‘s as a case morpheme at all[14]. The reasons she puts forward to substantiate her point of view are as follows:

1) The use of -'s is optional (her brother's, of her brother).

2) It is used with a limited group of nouns outside which it occurs very seldom.

3) -'s is used both in the singular and in the plural (child's, children's), which is not incident – to case morphemes (cf. мальчик‑а, мальчик-ов).

4) It occurs in very few plurals, only those with the irregular formation of the plural member (oxen's but cows').

5) -'s does not make an inseparable part of the structure of the word. It may be placed at some distance from the head-noun of an attributive group.

«Been reading that fellow what's his name's attacks in the 'Sunday Times'?» (Bennett).

Proceeding from these facts G.N. Vorontsova treats -'s as a 'postposition', a 'purely syntactical form-word resembling a preposition', used as a sign of syntactical dependence[15].

In keeping with this interpretation of the -'s morpheme the author denies the existence of cases in Modern English.

At present, however, this extreme point of view can hardly be accepted[16]. The following arguments tend to show that -'s does function as a case morpheme.

1. The -'s morpheme is mostly attached to individual nouns e, not noun groups. According to our statistics this is observed in 96 per cent of examples with this morpheme. Instances like The man I saw yesterday's son are very rare and may be interpreted in more ways than one. As already mentioned, the demarcation line between words and combinations of words is very vague in English. A word-combination can easily be made to function as one word.

Cf. a hats-cleaned-by-electricity-while-you-wait establishment (O. Henry), the eighty-year-olds (D.W.).

In the last example the plural morpheme – s is in fact attached to an adjective word-combination, turning it into a noun. It can be maintained that the same morpheme –‘s likewise substantives the group of words to which it is attached, and we get something like the man‑1‑saw-yesterday's son.

2. Its general meaning – «the relation of a noun to an other word» – is a typical case meaning.

3. The fact that -'s occurs, as a rule, with a more or less limited group of words bears testimony to its not being a «preposition-like form word». The use of the preposition is determined, chiefly, by the meaning of the preposition itself and not by the meaning of the noun it introduces (Cf. оn the table, in the table, under the table, over the table etc.)

4. The fact that the possessive case is expressed in oxen – oxen's by -'s and in cows – cows' by zero cannot serve as an argument against the existence of cases in English nouns because -'s and zero are here forms of the same morpheme

a) Their meanings are identical.

b) Their distribution is complementary.

5. As a minor argument against the view that -'s is «a preposition-like word», it is pointed out[17] that -'s differs phonetically from all English prepositions in not having a vowel, a circumstance limiting its independence.

Yet, it cannot be denied that the peculiarities of the -'s morpheme are such as to admit no doubt of its being essentially different from the case morphemes of other languages. It is evident that the case system of Modern English is undergoing serious changes.

Похожие работы

... . – The fence has just been painted. The fact that the indefinite to this graduation of dynamism in passive constructions. Chapter II. Contextual and functional features of the Passive forms in English and Russian 2.1 The formation of the Passive Voice The passive voice is formed by means of the auxiliary verb to be in the required form and Participle II of the notional verb. a) The ...

... . 6. The Scandinavian element in the English vocabulary. 7. The Norman-French element in the English vocabulary. 8. Various other elements in the vocabulary of the English and Ukrainian languages. 9. False etymology. 10.Types of borrowings. 1. The Native Element and Borrowed Words The most characteristic feature of English is usually said to be its mixed character. Many linguists ...

... complications can be combined: Moira seemed not to be able to move. (D. Lessing) The first words may be more difficult to memorise than later ones. (K. L. Pike) C H A P T E R II The ways and problems of translating predicate from English into Uzbek. 1.2 The link-verbs in English and their translation into Uzbek and Russian In shaping the predicate the differences of language systems ...

... types of morphemes. The latter can be studied from the point of view of two complementary analyses. 2. The semantics of the affixes and their comparative analysis affix negative morpheme semantic The first step in our studying English negative affixes is to give a definition of the affix itself. Here is a definition given in Oxford Advanced Lerner’s Dictionary of Current English. Affix is a ...

0 комментариев