Íàâèãàöèÿ

Palmer’s and mind’s discussion on English modality

2.6 Palmer’s and mind’s discussion on English modality

Historically in language descriptions, the grammatical terms «modality» and «mood» have lacked truly definitive categories of meaning. For that reason, linguistic dictionaries have often treated them as synonyms, cross referencing their entries and in some cases, describing how different theories or authors have used the terms.

In this book, Palmer treats «modality» as a valid cross-language grammatical category that, along with tense and aspect, is notionally concerned with the event or situation that is reported by an utterance. However, he says that unlike tense and aspect which are categories associated with the nature of the event itself, modality is concerned with the status of the proposition that describes the event.

Palmer then goes on to define two basic distinctions in how languages deal with the category of modality: modal systems and mood. He believes that many languages may be characterized by one or the other. He also claims that typology related to modality cannot be undertaken on purely formal grounds because of the complexity of cross-linguistic differences in the grammatical means used to express what he terms «notional» categories. This claim is substantiated by the great variety of forms and structures evident in the data from 122 languages that he uses to illustrate the expression of modality.

Palmer distinguishes two sorts of modality: propositional modality and event modality. These notional systems express the following categories:

Propositional modality

Epistemic – speakers express their judgment about the factual status of the proposition

Speculative: expresses uncertainty

Deductive: expresses inferences from observable data

Assumptive: expresses inferences from what is generally known

Evidential: speakers give evidence for the factual status of the proposition

Reported – evidence gathered from others

Sensory: evidence gathered through sense perception, e.g., seen, heard

Event modality

Deontic: speakers express conditioning factors that are external to the relevant individual

Permissive: permission is given on the basis of some authority, e.g. rules, law, or the speaker

Obligative: an obligation is laid on the addressee(s), also on the basis of some authority

Commissive: a speaker commits himself to do something; the expression may be a promise or a threat

Dynamic: speakers express conditioning factors that are internal to the relevant individual

Abilitive: expresses the ability to do something

Volitive: expresses the willingness to do something

These notional categories are discussed and illustrated throughout the book.

The illustrative data reveal many of the formal means for expressing the notional categories in a variety of languages. According to Palmer, three grammatical categories predominate in the expression of the notional categories: (1) affixation of verbs, (2) modal verbs, and (3) particles. Many of the languages from which Palmer chose data use more than one grammatical category to express the notions.

This is probably not unusual. In fact, the two Austronesian languages with which I am most familiar spread the notions across all three grammatical categories, and the lexical and morphosyntactic patterns are completely unlike English patterns, although the similarity of notions is fairly obvious. I would expect to see a closer correlation of the grammatical means of expessing modality among related languages.

Palmer discusses the use of modal verbs and their association with possibility and necessity in chapter 4. He draws together issues involving epistemic modality, i.e., a speaker’s attitude to the truth value or factual status of a proposition in contrast to deontic and dynamic modality that refer to unactualized events. Although notionally there is a difference, Palmer explains that in English and many other languages, the same modal verbs are used for both types. He gives three English sentences as examples:

(1) He may come tomorrow.

(2) The book should be on the shelf.

(3) He must be in his office.

He states that each of the modal verbs in the sentences can express either epistemic or deontic modality. However, he goes on to say in a later section that there are some formal differences: deontic must and may can be negated whereas epistemic must and may cannot be; if may and must are followed by have in a clause, they always express epistemic modality, never deontic; another formal difference between may and must is that deontic may is replaceable by can and would still express deontic modality, but if replaced by can’t it would then likely express epistemic modality, i.e., a truth value. This type of illustration and explanation is used throughout the book.

Palmer discusses the links between mood and modal systems with particular respect to languages that express mood formally, or in combination with modal notions. Although Palmer suggests that there is basically no typological difference between indicative/subjunctive and realis/irrealis since both are instances of mood, he does state that there are considerable differences between the functions of what have been labeled «subjunctive» and «irrealis» For that reason he deals with them in three separate chapters.

Although Palmer’s notional categories make sense, I found that it was difficult to process the grammatical patterns in the language data used to illustrate the categories. Part of my difficulty may be attributed to the fact that I believe modality needs to be studied in the context of use, i.e., natural texts, not isolated sentences; and also, I believe, that a thorough study of all grammatical expressions of modality and mood must be done within a single language before the results are compared and contrasted cross-linguistically. Perhaps the authors of the papers and grammars that Palmer used had done just that, but the contexts were lost through the excerpting of sentences to illustrate his notional categories.

In spite of this criticism, I found Palmer’s categories, his compilation of data from many different languages, and explanations of terminological usage very helpful in my own work, as well as thought provoking. I wholeheartedly recommend the book for your reference shelf, particularly if you are a linguist or translator who needs to do an in-depth study of modality in a single language or a cross-language comparison of modality.

In his preface, the author explains that this volume is a complement to an earlier

volume, titled An Empirical Grammar of the English Verb: Modal Verbs, published in 1995 by the same publisher. The present volume clearly aims to provide an inventory of the various verb combinations within the English verb phrase. This is done on the basis of the study of a large amount of corpus data. I am not so sure whether the term grammar in the title is entirely justified, for even though information about distribution and frequency of occurrence of the various patterns is provided, the book hardly ever goes beyond providing this kind of information. The author writes in his introduction that «all instances of verbs and verb phrases can be explained as cases of rule-governed grammatical behavior,» but what these rules are is not explained anywhere. I will come back to this below.

The book definitely has a number of strong points, but it also has quite a number of serious shortcomings. Let me first discuss the general contents of the book. It is divided into seven chapters: «Introduction» «General Categories» «Verb Forms».

«Verb Phrases» «Finite Verb Phrases» «Non-finite Verb Phrases» and «Time Orientation».

In the introduction, the author explains the inductive approach he has followed.

Basically, there are three steps: from language to verb patterns and their contexts, from database creation (i.e., storing the verb patterns identified) to linguistic analysis of verb patterns, and from the results of these analyses to a grammar of the English verb. He also states (6) that the grammar is based on authentic English and that there has been no borrowing from previous grammars. This is probably also why there is no reference section. They are useful for a quick first impression. In the prototypes, the author claims, the users of the book will find the most frequent patterns they are likely to encounter «in texts or in contact with speakers of the language» (12). The details, finally, give information on form (full vs. contracted forms, which the author persistently calls «elided» forms), meaning, and context. In the latter, contextual information is given on affirmative and negative contexts, declarative and interrogative contexts, combination with subjects, combination with verbs, and other syntactic information.

Some of this information is certainly useful, but a lot of it is repetitive and could well have been stated generally. For instance, in the contexts of nearly all the patterns, it is said that affirmative contexts are far more frequent than negative contexts and that declarative contexts are far more frequent than interrogative contexts, the percentages being roughly 90 for affirmative and 10 for negative and another 90 for declarative and 10 for interrogative, give or take a point or two. This information could have been formulated once, under a general heading, after which contexts with a clearly deviant distributional pattern could have been appropriately highlighted and commented on, as in the case of be allowed to, which occurs in a negative context in 23 percent of all cases (400). Incidentally, the author apparently only considers the occurrence of the word not (or n’t) to be an indication of a negative context, for on the same page he quotes the sentence nobody should be allowed to forget it as an example of an affirmative context (400). This, and the lack of comment, makes the book really little more than a mere listing of examples of the various patterns distinguished.

«General Categories,» briefly discusses the concept of time, temporal orientation, and temporal reference. Temporal orientation can be past, present, or future, while time reference can be preceding, simultaneous, following, or neutral.

Thus, the sentences below (listed on page 19) all have past time orientation but have preceding, simultaneous, following, and neutral reference, respectively, the reference indicated by the highlighted verb phrases.

Lee, I noticed, had asked for a Coca-Cola

But what he saw was an ageing Australian woman

She was glad that he would be with her

He won because he’s forty years younger than you

Only time orientation, however, is indicated for the various verb phrase patterns distinguished «because of the intricacies of time reference» (19). It makes sense to make an inventory of the time orientation of the verb phrase patterns because after all this orientation is somehow expressed by the tense of the verb phrase (although this does not apply to nonfinite verb phrases). It makes equal sense to make an inventory of real and nonreal states or events referred to by the verb phrase patterns because, again, this is indicated by the tense or modality expressed by the verb phrase. I find it less natural to make an inventory of restrictive or nonrestrictive meaning expressed particularly by nonfinite verb phrases (21), for this distinction is not inherent in the verb phrase itself. Moreover, it can only refer to a relatively small subset of nonfinite clauses–namely, those with an attributive function.

The final category that Mindt distinguishes as relevant to the description of the verb phrases is the nature of the subject with which they are associated. Mind distinguishes between intentional and nonintentional subjects (22), but he does not really explain the difference at all convincingly. He merely provides a few examples of each, giving the reader the impression that the distinction more or less coincides with human and nonhuman subjects, for he then says, «Because of the relation between verb phrase and intentional and non-intentional subjects, the distinction between intentional and non-intentional has to be made no matter whether the subject is acting intentionally or not» (22). Thus, in most patients are taught to do this, we have an intentional subject, whereas in more techniques are taught, we have a nonintentional subject. It would seem to me that Mindt has thought of a category, then found that it is not useful at all in many cases but has decided to hang onto it in spite of this.

«Verb Forms» is a very straightforward chapter spelling out the details of verb forms, verb morphology, inflection, spelling rules, and patterns of irregular verbs. This chapter concludes with a learning list of irregular verbs, based on the rank list compiled, one assumes, on the basis of the corpora listed in the appendix.

Fortunately, there is also an alphabetical list of irregular verbs.

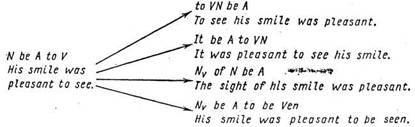

«Verb Phrases,» discusses verb phrase types. Mindt uses a three dimensional graphic representation of verbal elements that can occur in a verb phrase and the order in which they occur. This model was introduced in An Empirical Grammar of the English Verb: Modal Verbs (Mindt 1995). The model enables Mindt to account for a great variety of verb phrase patterns, in which all kinds of combinations of modals, auxiliaries, so-called catenative verbs, and main verbs can be combined in specific ways. The main problem with this chapter (as with the following two) is the justification of (or rather the failure to justify) the existence of the category of catenative verbs. The catenative verbs are said to be a group of «chaining» verbs (which is exactly what the term catenative means) whose function is apparently to link elements in a verb phrase together. Catenative verbs do not share any characteristics with modal verbs and very few with primary auxiliaries. Examples of catenative verbs are seem or begin. While there are admittedly very good reasons for wishing to distinguish a category such as catenative verbs, Mindt fails to present any convincing arguments for this. Moreover, he includes verbs in this category that should not be included by any standard, such as want, avoid, mean, enjoy, or be important. Worst of all, in his illustrations of how so-called catenative verb phrases are distinguished from «noncatenative» verb phrases, he seems to ignore elements of well-established modern descriptive grammars of English.

For instance, in the sentence we want you to come with us (112), the main clause is said to be we want you and the subclause to come with us, and you is said to be the object of the main clause and the «semantic subject» of the subclause. This appears to take us right back to Zandvoortian times and to ignore the fact that there are very simple constituency tests that would tell you that in this case, for instance, it does not make sense to ask who do we want? but it would make sense to ask what do we want? – thus ruling out you as an object of the main clause.

In the sentence he wanted to talk to Armstrong (111), wanted to talk is a catenative verb phrase, with wanted a catenative verb, but in the sentence quoted above (we want you to come with us), want and to come are separate verb phrases, with both want and come as main verbs. Mindt argues (471) that the distinction of the category of catenative verbs reduces the number of nonfinite verb phrases, implying that this makes the description of sentences more straightforward. I am not convinced that that is true. Moreover, an important generalization is missed – namely, that verbs such as want are simply complemented by infinitive clauses, with or without a subject of their own.

Another example of a catenative verb occurs in the sentence the authorities failed to respond speedily (111). Again, no argumentation is provided. Mindt could have argued that failed cannot be assigned main verb status (e.g., because failed basically means no more than did not) and therefore should be looked on as a catenative verb, making up a single verb phrase with the following main verb respond.

In the book, we can only guess what traditional descriptions and which previous grammars he means. But what he claims is not quite true, of course, for Quirk et al. (1972) do distinguish a separate category of semi-auxiliary verbs, including verbs such as seem and happen (in Quirk et al. 1985, these verbs are also termed catenative verbs, by the way).

I find the discussion of catenative verbs particularly problematic because Mindt does not provide any proper syntactic arguments, a state of affairs that leads him to include an excessive number of verbs in this category. For instance, the verb want is included (see the example above) on the strength of the argument that catenative verbs «allow overlap of two meanings within one verb phrase. This overlap cannot be achieved by modals alone, because a verb phrase cannot contain more than one modal verb. Thus, Mindt claims, possibility/high probability can be expressed by might, as in fever might kill him. Volition/intention can be achieved by will, as in I will not be a soldier. If we want to combine these two, Mindt argues, we cannot simply combine might with will, but instead we can combine might with the catenative want to express volition/intention, as in they might want to kill us. The flaw in this argument, I think, is that want does not simply express volition/intention but desire, which is not the same thing.

Mindt overlooks the rather basic fact that propositional content is expressed by the lexical verb in a clause and that all subordinate verbs in the verb phrase do not add any propositional content, but only such things as modality, aspect, and so on.

This can easily be tested by comparing active and passive counterparts, which should express the same proposition. For instance, on the basis of the sentence pair Harry kissed Jane/Jane was kissed by Harry, we can equate the following pairs:

Harry has kissed Jane = Jane has been kissed by Harry

Harry will kiss Jane = Jane will be kissed by Harry

Harry may have kissed Jane = Jane may have been kissed by Harry

Harry appeared to kiss Jane = Jane appeared to be kissed by Harry but not the following:

Harry wanted to kiss Jane ≠ Jane wanted to be kissed by Harry which shows that want adds propositional content to these sentences and should therefore be looked on as a lexical, rather than a catenative, verb.

Mindt also distinguishes a group of catenative verbs followed by present participles, suchas continue, start, keep, and so on (321 ff.). Here too, a number of verbs are included that clearly do not belong there, such as consider, enjoy, avoid, mean.

Again, Mindt does not use a rather simple constituency test to make the distinction.

It would be simple enough to compare he kept going for ten hours to he enjoyed possessing his knowledge on his own by applying a pronominalization test, which would show that it is impossible to paraphrase the former sentence above by he kept it but perfectly possible to paraphrase the latter by he enjoyed it, thus giving separate constituency status to the bit that follows enjoy but not to the bit following keep.

Finally, there is a category of catenative adjective constructions, such as be able to and be likely to (404) (incidentally, these are called semi-auxiliaries in Quirk et al. 1985). Regrettably, Mindt erroneously includes a number of cases of extraposed subject clauses here, such as it is necessary to go back in time and it could be important to record facts, where the supposed catenative verbs are be necessary to and be important to. This kind of error should not have occurred in a book like this. on nonfinite verb phrases, a three-way distinction is made between verbal to-infinitives, verbal to-infinitives preceded by be, and gerundial to infinitives.

This amounts basically to the clause functions of adverbials, subject complements, and subjects of NP modifiers, respectively. However, in the first group, we find the example it’s impossible to be accurate about these things (472 – highlighting Mindt’s). One wonders why be possible to is listed earlier, as a catenative adjective construction while be impossible to is apparently something else. Of course, this is again a case of an extraposed subject clause and should therefore, if anything, have been listed as a gerundial to-infinitive.

Mindt discusses the patternVERBPHRASE + DIRECT OBJECT + TO-INFINITIVE. This makes one think of Zandvoort’s (1945) Accusative with Infinitive constructions. Again, Mindt is not very careful here, for here he lists verbs suchas want, ask, tell, allow, expect, persuade, cause. These are precisely the verbs that grammarians and generative linguists alike have used over the years to demonstrate different types of verb complementation, based on the differences in syntactic behavior of the complements of these verbs.

The concept of meaning, like other concepts, is not explained but rather exemplified.

This leads to distinctions that are fairly arbitrary, such as the distinction of the two meanings of the catenative constructionHAVE (TO) (298), which is said to express either necessity or obligation. The following examples are given, without any further comment:

Necessity: I have to speak to you about Pepita’s education among other things you’ll have to stand up for yourself Obligation: the man had to retire at sixty one of us will have to go in the end This leaves one wondering what the distinction is based on. Is it based on the possibility of paraphrasing the former two by it is/was necessary that… and the latter by there is/was an obligation/order…? I do not know, and frankly, the examples do not even convincingly point in this direction.

In the discussion of the prototypes of the progressive (254 ff.), Mindt distinguishes four types, expressing incompletion, temporariness, iteration/habit, and highlighting/prominence, respectively. He then goes on to describe each of these prototypes in more detail. Curiously, hardly any of the prototypes are found to be pure types: they nearly always combine with elements of other prototypes. So what is meant by the «prototypes» is probably aspects of meaning. Incidentally, in the discussion of incompletion, it is said that in 30 percent of the cases, it is combined with temporariness (257)[7]. In the discussion of temporariness (258), it is said that in 50 percent of the cases, it combines with incompletion. It is hard to compare these figures to each other since no absolute figures are provided. Also, Mindt does not indicate whether there is possibly a difference between the combination temporariness + incompletion and incompletion + temporariness. However, what is clear from these examples is that the really typical progressive form combines the aspects of incompletion and temporariness. But this conclusion is not in the book.

All in all, there are too many of these infelicities in this book. What exactly is a verb phrase is not clarified. The book would have been so much more valuable if the classifications had been shown to have been made on the basis of syntactic arguments.

It would undoubtedly also have meant that certain erroneous classifications would have been avoided. As it is, the book can be no more than an inventory of examples of English verbal patterns, which may be used as a resource for course book designer.

In syntax, a verb is a word belonging to the part of speech that usually denotes an action (bring, read), an occurrence (decompose, glitter), or a state of being (exist, stand). Depending on the language, a verb may vary in form according to many factors, possibly including its tense, aspect, mood and voice. It may also agree with the person, gender, and/or number of some of its arguments (subject, object, etc.).

The number of arguments that a verb takes is called its valency or valence. Verbs can be classified according to their valency:

Intransitive (valency = 1): the verb only has a subject. For example: «he runs», «it falls».

Transitive (valency = 2): the verb has a subject and a direct object. For example: «she eats fish», «we hunt deer».

Ditransitive (valency = 3): the verb has a subject, a direct object and an indirect or secondary object. For example: «I gave her a book,» «She sent me flowers.»

It is possible to have verbs with zero valency. Weather verbs are often impersonal (subjectless) in null-subject languages like Spanish, where the verb llueve means «It rains The Tlingit language features a four way classification of verbs based on their valency. The intransitive and transitive are typical, but the impersonal and objective are somewhat different from the norm. In the objective the verb takes an object but no subject, the nonreferent subject in some uses may be marked in the verb by an incorporated dummy pronoun similar to the English weather verb (see below). Impersonal verbs take neither subject nor object, as with other null subject languages, but again the verb may show incorporated dummy pronouns despite the lack of subject and object phrases. Tlingit lacks a ditransitive, so the indirect object is described by a separate, extraposed clause. [citation needed].

English verbs are often flexible with regard to valency. A transitive verb can often drop its object and become intransitive; or an intransitive verb can be added an object and become transitive. Compare:

I turned. (intransitive)

I turned the car. (transitive)

In the first example, the verb turn has no grammatical object. (In this case, there may be an object understood – the subject (I/myself). The verb is then possibly reflexive, rather than intransitive); in the second the subject and object are distinct. The verb has a different valency, but the form remains exactly the same.

Conclusion

In many languages other than English, such valiancy changes aren't possible like this; the verb must instead be inflected for voice in order to change the valency. [citation needed]

A copula is a word that is used to describe its subject, [dubious – see talk page] or to equate or liken the subject with its predicate. [dubious – see talk page] In many languages, copulas are a special kind of verb, sometimes called copulative verbs or linking verbs.

Because copulas do not describe actions being performed, they are usually analysed outside the transitive/intransitive distinction. [citation needed] The most basic copula in English is to be; there are others (remain, seem, grow, become, etc.). [citation needed]

Some languages (the Semitic and Slavic families, Chinese, Sanskrit, and others) can omit the simple copula equivalent of «to be», especially in the present tense. In these languages a noun and adjective pair (or two nouns) can constitute a complete sentence. This construction is called zero copula.

Most languages have a number of verbal nouns that describe the action of the verb. In Indo-European languages, there are several kinds of verbal nouns, including gerunds, infinitives, and supines. English has gerunds, such as seeing, and infinitives such as to see; they both can function as nouns; seeing is believing is roughly equivalent in meaning with to see is to believe. These terms are sometimes applied to verbal nouns of non-Indo-European languages.

In the Indo-European languages, verbal adjectives are generally called participles. English has an active participle, also called a present participle; and a passive participle, also called a past participle. The active participle of give is giving, and the passive participle is given. The active participle describes nouns that perform the action given in the verb, e.g. a giving person. [dubious – see talk page] The passive participle describes nouns that have been the object of the action of the verb, e.g. given money Other languages apply tense and aspect to participles, and possess a larger number of them with more distinct shades of meaning. [citation needed]

In languages where the verb is inflected, it often agrees with its primary argument (what we tend to call the subject) in person, number and/or gender. English only shows distinctive agreement in the third person singular, present tense form of verbs (which is marked by adding «– s»); the rest of the persons are not distinguished in the verb.

Spanish inflects verbs for tense/mood/aspect and they agree in person and number (but not gender) with the subject. Japanese, in turn, inflects verbs for many more categories, but shows absolutely no agreement with the subject. Basque, Georgian, and some other languages, have polypersonal agreement: the verb agrees with the subject, the direct object and even the secondary object if present.

Bibliography

1. Language Log: How to defend yourself from bad advice about writing The American Heritage Book of English Usage, ch. 1, sect. 24 «double passive» Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996

2. «Double Your Passive, Double Your Fun» from Literalminded. http://literalminded.wordpress.com/2005/05/16/double-your-passive-double-your-fun/. Accessed 13 November 2006.

3. Bybee, Joan L., Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca (1994) The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World. University of Chicago Press.

4. Comrie, Bernard (1985) Tense. Cambridge University Press. [ISBN 0–521–28138–5]

5. Downing, Angela, and Philip Locke (1992) «Viewpoints on Events: Tense, Aspect and Modality». In A. Downing and P. Locke, A University Course in English Grammar, Prentice Hall International, 350–402.

6. Guillaume, Gustave (1929) Temps et verbe. Paris: Champion.

7. Hopper, Paul J., ed. (1982) Tense-Aspect: Between Semantics and Pragmatics. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

8. Smith, Carlota (1997). The Parameter of Aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

9. Tedeschi, Philip, and Anne Zaenen, eds. (1981) Tense and Aspect. (Syntax and Semantics 14). New York: Academic Press.

10. Mindt, D. 1995. An Empirical Grammar of the English Verb: Modal Verbs.

11. Quirk, R., S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, and J. Svartvik. 1972. A Grammar of

12. Zandvoort, R. 1945. A Handbook of English Grammar. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff.

13. Ãðàììàòèêà àíãëèéñêîãî ÿçûêà (íà àíãëèéñêîì ÿçûêå) / Ïîä ðåä. Â.Ë. Êàóøàíñêîé. – 4‑å èçä. – Ë.: Ïðîñâåùåíèå, 1973. – 319 ñ.

14. Ãðàììàòèêà ñîâðåìåííîãî àíãëèéñêîãî ÿçûêà: A new university English grammar: Ó÷åáíèê äëÿ ñòóä. âûñø. ó÷åá. çàâåäåíèé / Ïîä ðåä. À.Â. Çåëåíùèêîâà, Å.Ñ. Ïåòðîâîé. – Ì.; ÑÏá.: Academia, 2003. – 640 ñ.

15. Ãóðåâè÷ Â.Â. Òåîðåòè÷åñêàÿ ãðàììàòèêà àíãëèéñêîãî ÿçûêà. Ñðàâíèòåëüíàÿ òèïîëîãèÿ àíãëèéñêîãî è ðóññêîãî ÿçûêîâ: Ó÷åá. ïîñîáèå. – Ì.: Ôëèíòà, Íàóêà, 2003. – 168 ñ.

16. Ãóðååâ Â.À. Ó÷åíèå î ÷àñòÿõ ðå÷è â àíãëèéñêîé ãðàììàòè÷åñêîé òðàäèöèè (XIX–XX ââ.) – Ì., 2000. – 242 ñ.

17. Internet:http://www.englishclub.com/grammar/articles/theory/the

18. Internet:http://www.englishlanguage.ru/main/studyarticles/

19. Internet:http://www.esllessons.edu/mainpage/lessonplans/articles.htm

20. Internet:http://www.freeesays.com/languages/S. Hal How to Learn English grammar.htm

21. Internet:http://www.yandex.narod.ru/filolog.ru/grammarunits/îá Äèäêîâñêàÿ

22. Wheeler C.J., Schumsky D.A. The morpheme boundaries of some English derivational suffixes // Glossa. – Burnaby, 1980. – Vol. 14, ¹1. – P. 3–34.

23. Woisetschlaeger E.F. A semantic theory of the English auxiliary system. – New York; London: Garland, 1985. – 127 p.

24. Wolfgang U.D. Morphology // Handbook of discourse analysis. – Vol. 2. Dimensions of discourse. – London; Tokyo, 1985. – P. 77–86.

[1] Language Log: How to defend yourself from bad advice about writing The American Heritage Book of English Usage, ch. 1, sect. 24 "double passive." Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996

[2] Language Log: How to defend yourself from bad advice about writing The American Heritage Book of English Usage, ch. 1, sect. 24 "double passive." Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996. Accessed 13 November 2006

[3] Bybee, Joan L., Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca (1994) The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World. University of Chicago Press

[4] Bybee, Joan L., Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca (1994) The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World. University of Chicago Press

[5] Bybee, Joan L., Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca (1994) The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World. University of Chicago Press

[6] Guillaume, Gustave (1929) Temps et verbe. Paris: Champion

[7] Guillaume, Gustave (1929) Temps et verbe. Paris: Champion

Ïîõîæèå ðàáîòû

... mean, however, that the grammatical changes were rapid or sudden; nor does it imply that all grammatical features were in a state of perpetual change. Like the development of other linguistic levels, the history of English grammar was a complex evolutionary process made up of stable and changeable constituents. Some grammatical characteristics remained absolutely or relatively stable; others were ...

... complications can be combined: Moira seemed not to be able to move. (D. Lessing) The first words may be more difficult to memorise than later ones. (K. L. Pike) C H A P T E R II The ways and problems of translating predicate from English into Uzbek. 1.2 The link-verbs in English and their translation into Uzbek and Russian In shaping the predicate the differences of language systems ...

... clear and lucid language. There are some problems which are debated up to now, for example, «the reality of the perfective progressive». 1.3 The analysis of the stylistic potential of tense-aspect verbal forms in modern English by home linguists N.N. Rayevska [3; 30] is a well-known Ukrainian (Kiev) scholar who specialized in the study of English language and wrote two monographs: 1. The ...

... laws. The comparison of the system of two languages are compared first of all. E.g. the category of mood in English is considered to be a small system. Having completed the comparison of languages investigators takes the third language to compare and so on. Comparative typology is sometimes characterized by some scholars as characterology which deals with the comparison of the systems only. ...

0 êîììåíòàðèåâ