Íàâèãàöèÿ

Ben Jonson and his Comedies

MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN

GULISTAN STATE UNIVERSITY

The English and Literature Department

Qualification work on speciality English philology

on the theme:

“Ben Jonson and his comedies.”

Tojieva Dilnoza’s qualification work

on speciality 5220100

Supervisor: Tojiev Kh.

Gulistan-2006

Introduction Some notes on Ben Johnson’s Works

Born in 1572, Jonson began his working life as a bricklayer and then a soldier, and it is perhaps experiences in these fields – and his prodigious intake of falling down water – that shaped his no-nonsense, confrontational personality.

Jonson became an actor after serving in the army in the Netherlands. By all accounts, he was not a very good actor, but during his time with Pembroke's Men he co-authored a play, "Isle of Dogs," with Nashe. The play, accused of spreading sedition, would lead to one of many brushes with the State, and he was imprisoned for some months.

Jonson wrote for the Admiral's Men until 1856, when a quarrel with Gabriel Spencer, one of the company's leading players, led to a duel. Spencer was killed and Jonson only spared execution by drawing on his knowledge of Latin to invoke the benefit of the clergy, which enabled the convicted criminal to pass as a clergyman, and therefore obtain a discharge from the civil courts. It is believed that while in Newgate Prison he converted to Roman Catholicism, and here was branded on his thumb with the "T" for Tyburn (the most famous place of execution in London after the Tower) to ever more remind him of his lucky escape.

Jonson's first box office successes came about with comedies like "Every Man In His Humour," which featured Shakespeare in the cast. It is thought Shakespeare was probably the one who first championed Jonson as a writer of note. Jonson's method of working began to crystallize about this time, and he began to produce more hard-edged, biting satire dispensing with a lot of the farce and frippery that were Shakespeare's tools. As his work became ever more distinctive and classically inspired he began to heap disdain on other writers and their work.

Boys' Company performance of "Poetaster"In the early 1600's, Jonson embraced a new phenomenon. Boys Companies were as seductive to audiences and as threatening to Shakespeare's brand of theatre as N*Synch and Boys 2 Men were to today's Springsteens, REMs and Rolling Stones.

Boys Companies were highly trained in vocal and instrumental music, and with their youthful looks and skin were probably a lot easier to relate to in women's roles than the half shaved, former soldiers of the adult theatre companies.

Jonson, the classical scholar, and Shakespeare, the populist crowd-pleaser as Jonson saw him, even came to blows in a "discussion" over the merits, or otherwise, of the Boys Companies. A protracted, and wordy, War of the Poets ensued, with both sides of the argument trading digs and insults through their work.

Imagine an episode of the TV show Frasier that lasts three years, and features an unbroken argument between Niles and Frasier Crane on the relative merits of Jung and Freud, and you get the general idea.

Jonson would find himself in trouble with the State time and time again – for ridiculing the Scots in "Eastward Ho!" and most seriously when he was questioned over the gunpowder plot, after which he renounced his "provocative" Roman Catholicism. Later his play, "Sejanus," would also fall foul of the censors.

Jonson, always something of a misunderstood outsider in his own writing, would comment on his lot at the hands of a society rife with envy and suspicion:

Know, tis a dangerous age,

Wherein who writes had need present his scenes

Forty-fold proof against the conjuring means

Of base detractors and illiterate apes

(It's interesting that spooky rock person Marilyn Manson has been quoted as referring to Limp Bizkit's front man Fred Durst as an "illiterate ape," Manson being another artistic figure who felt his work was being misrepresented after the atrocious events at Columbine.)

With the arrival of James I on the throne, Jonson found himself in favor once again, and, with his co-writer Inigo Jones, created Court Masques for Queen Anne until their inevitable quarrel. Jonson and Shakespeare seem to have called a truce on their dispute and become close again around 1609. Until Shakespeare's death they seem to have continued their almost good natured jibes and sniping, with Jonson typically dismissing his friend as having "small Latin and less Greek."

Ben Jonson clearly saw himself as a champion of intellectualism – totalitarian states often don't care for intellectuals to the point that they will generally kill most of them. Shakespeare could ultimately be said to be cleverer in diluting his classical influences to reach a wider audience. It's that old Hollywood-versus-arthouse debate.

It was said at the time that "gentle Will" Shakespeare showed Jonson a courtesy that was not returned. Jonson certainly seems to have been brusque and volatile, a matter not helped by his drinking. Everyone drank alcohol in Elizabethan and Jacobean London because the quality of the available drinking water was so bad. But Jonson literally turned it into an art form, composing whole poems about his favorite drinking holes.

There seems to have been an almost brotherly relationship between Jonson and Shakespeare. Though their rivalry was strong, and their verbal jibes at each other cutting, both seemed to recognize the talent in each other – Jonson grudgingly, Shakespeare more generously. They seem to have spent a great deal of time in each other's company. It is believed that Shakespeare may have become ill prior to his death after a typically uproarious night out drinking (something strong and noxious, probably with an odd name like Left Leg) with Jonson and others.

Ultimately it was Jonson – perhaps his greatest and most constant critic – who gave Shakespeare his most enduring epitaph: "He was not of an age, but for all time."

Ben Jonson died in 1637.

Works by Ben Jonson:

"The Alchemist"

"Cynthia's Revels"

"Every Man in His Humour"

"Every Man out of His Humour"

"Poetaster"

"Volpone"

"Sejanus"

"Catiline"

"Bartholomew Fair"

"The Devil is an Ass"

"Staple of News"

"Eastward Ho!"

"Epicoene"

Main Part

Ben Jonson's Volpone: Issues and Considerations

1. The opening scene of the play (1.1.1-27) is often considered a satire of some sort on the Catholic Mass. If this is so and considering that Jonson was a Catholic at the time of the writing, why would the author include such a scene?

2. Volpone is set against a background of decadence and corruption in Venice. Renaissance (and Enlightenment) England was publicly suspicious of the supposed corruption that traveling to Italy brought. How does Jonson use this background to further the themes and purpose of his play? Are the images stereotypical?

3. How much is Volpone a play shaped by monetary fears and concerns? How much is it a play about the use and abuse of authority?

4. How would you map out the ascent, climax, and denouement of the main plot? Where does the scene between Celia and Volpone fall? Where do the two court scenes belong?

5. What is the purpose of the subplot involving Sir Pol, Lady Pol, and Peregrine? Does it in any way reflect on the larger plot?

6. What is the role of Nano, Castrone, and Androgyno?

7. How would you play the court Avocatori? Are they primarily serious or farcical characters?

8. How complicit are we as a audience with Volpone and Mosca's vices? Are they too attractive (at first) as characters? Why is Volpone given a chance to address the audience in the closing speech?

9. Is this a comedy? How do you account for the punishments awarded at the end, the vulgar attempted rape by Volpone, and the play's more serious moments? Is the ending comic?

Does this play have (in the end) a positive, ethical message? If so, what is it? If not, why not?

In addition to the reading assignment on the syllabus, please read through the material on this well-researched web page by a student (identified only as "Jason") in Professor Christy Desmet's Renaissance Drama course at the University of Georgia: Venice as the Setting for Volpone

1. In Act I, scene 1 (pp. 1131-2), Volpone lists the many means of making money (honestly and dishonestly) that he does not use. What is his "trade"? How does he make his money?

2. Trace the gold imagery in the first three acts. What functions does gold serve in the world of Volpone?

3. Jonson draws on animal fables for his characters' names and personalities. How does this technique affect your expectations as a reader? Does the text fulfill those expectations?

4. Other than Mosca, the only members of Volpone's household are his three servants (rumored to be his illigitimate children). In each of them, the natural body of a man has been in some way warped, mutilated, or curtailed: Nano is a dwarf, Androgyno a hermaphrodite (a person with characteristics of both sexes), and Castrone a eunuch (a castrated male). What is the effect of Volpone's bing surrounded by such creatures?

5. Note the performance given by Nano, Androgyno, and Castrone in Act 1, scene 2. It is a dramatic rendering of a popular Italian prose form, the paradox, in which the writer makes a witty display by considering (usually scornfully) some supposedly paradoxical assertion. Donne wrote some such prose paradoxes (e.g., "That a wise man is known by much laughing," which defends that idea in face of the usual proverb that you know a man is a fool if he's always laughing). Volpone's minions present a Praise of Folly. What is the point of this play within a play?

6. In Act 2, scene 1, Peregrine and Sir Politic Would-Be converse. How is this scene related to Act 1? And what is Peregrine's function in the play? How are we (as readers or audience members) to understand his role in relation to the other characters we have seen thus far?

7. In Act 2, scene 2, Volpone adopts the "disguise" he decided to use at the end of Act 1. Taking on the role of the mountebank Scoto of Mantua, he sets up a stage near the house of Corvino. His speeches in the person of Scoto are printed in italics. His act is to hawk "Scoto's Oil" ("oglio del Scoto"), a cure for all ills; how does his performance as Scoto compare to his performance as a dying man in Act 1?

8. Celia appears at her window and throws down a handkerchief full of coins to the supposed mountebank below. Why do you suppose she does this? And what do the various characters in the play assume to be her motivation? Does her motivation matter in the overall scheme of Jonson's play?

9. In scenes 6-7 of Act 2, Corvino's greed takes precedence over his jealousy, so that he becomes willing to become a bawd or pander (i.e., a pimp) selling his own wife to Volpone. Compare his speeches to Celia at the end of scene 5 (lines 48-73) and in scene 7 (lines 6-18). What ironies emerge from the language he uses in each case?

1. At the beginning of Act 3, Mosca speaks a grand soliloquy on his profession: that of the parasite. What is a parasite? Who qualifies as a "sub-parasite"? If "Almost / All the wise world is little else, in nature, / But parasites and sub-parasites," does anyone qualify as another kind of being?

2. Lady Politic Would-Be is, like Voltore, Corbaccio, and Corvino, a fortune-hunter. But is she in the same category with the other three? What, if anything, sets her apart? As you think about this question, take a look at this web page (again by Jason from the University of Georgia) on Courtesans in Venice.

3. What means does Volpone use in his attempt to seduce Celia in 3.7.139-154? In 154-164 of the same scene? In the "Song" that follows? And in 185-239? All of these attempts at seduction fail because of Celia's unassailable virtue. At what, if anything, do they succeed? Do they have an effect on you as a reader?

4. How do Volpone's addresses to Celia in 3.7 compare with his address to gold in 1.1?

5. Is there any shift in the degree to which the audience (or reader) identifies with Volpone and/or Mosca at various points in the play?

6. What does Peregrine's trick on Sir Pol add to the play's plot and theme?

7. With whom, if anyone, do the audience's (or reader's) sympathies lie in the play's final scenes?

8. Courtroom scenes are versions of the play-within-a-play technique, for lawyers and witnesses are performers very conscious of the audience that will judge them. How good are the performances in the courtroom scene of Act 5, scene 12? How does the courtroom "play" compare to the earlier plays-within-a-play (such as Volpone's deathbed act or his performance as Scoto)? How does the courtroom play-within-a-play relate to the play Volpone itself? That is, how do the performances in the courtroom (directed toward the judges) comment on that of the play Volpone (directed toward the theater audience)?

5. How do the various punishments meted out to Volpone, Mosca, and the others compare? Why are they so inequitable?

6. In Act 3, attempting to defend against the foul plans of her husband, Mosca, and Volpone, Celia declares her dedication to the preservation of honor (her own and her husband's). Corvino's response dismisses her scruples. Is Celia's view of honor vindicated by the end of the play?

7. The Norton introduction to the play speculates "that what Venice is in the play, England is about to become, in the city of London, the year of our Lord 1606"; and that Jonson, given his "vigorous social morality, would not have rejected" such an interpretation. Do you agree that Jonson's play is a warning for Englishmen about their own society?

Ben Jonson : Volpone

In his earlier plays, Jonson had made characters speak bitterly, expressing direct and dangerous attacks on the social manners of the higher classes. In Volpone that never happens. The Prologue boasts that it was written in five weeks (Jonson was usually a slow writer), all by Jonson himself. Then the play is compared with the more vulgar kind of play where there is horseplay and clowning:

And so presents quick comedy refined,

As best critics have designed;

The laws of time, place, persons he observeth,

From no needful rule he swerveth.

All gall and copperas from his ink he draineth,

Only a little salt remaineth. . .

The setting is Venice. Act One begins, as Volpone (the 'fox') and his close servant Mosca (the 'fly') celebrate Volpone's morning 'worship' of his gold:

VOLPONE. Good morning to the day; and next, my gold!

Open the shrine, that I may see my saint.

(Mosca opens the curtain that hides much treasure)

Hail the world's soul, and mine! more glad than is the teeming earth to see the longed-for sun peep through the horns of the celestial ram, am I, to view thy splendour darkening his;

That lying here, amongst my other hoardes, show'st like a flame by night, or like the day Struck out by chaos, when all darkness fled unto the centre. O thou son of Sol, but brighter than thy father, let me kiss, with adoration, thee, and every relic of sacred treasure in this blessed room. Well did wise poets by thy glorious name title that age which they would have the best;

Thou being the best of things, and far transcending all style of joy, in children, parents, friends, or any other waking dream on earth. Thy looks when they to Venus did ascribe, they should have given her twenty thousand Cupids, such are thy beauties and our loves! Dear saint, Riches, the dumb god, that givest all men tongues, that canst do nought, and yet mak'st men do all things;

The price of soul; even hell, with thee to boot, is made worth heaven. Thou art virtue, fame, honour and all things else. Who can get thee, he shall be noble, valiant, honest, wise - After this blasphemous adoration, Mosca flatters Volpone, stressing that his fortune was was not made by oppressing the poor. Then in a soliloquy, Volpone exposes his method:

I have no wife, no parent, child, ally, to give my substance to, but whom I make must be my heir; and this makes men observe me.

This draws new clients daily to my house, women and men of every sex and age, that bring me presents, send me plate, coin, jewels, with hope that when I die (which they expect each greedy minute) it shall then return Tenfold upon them.

Shakespeare, in Richard III and other plays, had already exploited the fact that, in theatre, 'all the world loves a villain.' Volpone is a shameless villain, quite open about his deceptions, inviting the audience (through Mosca) to admire his skills at manipulating human greed. The play then has an 'interlude' in which Volpone's 'creatures' -- a dwarf, an eunuch and a fool -- entertain him in grotesque imitation of court entertainments.

The action begins with the arrival, one by one, of Volpone's 'clients,' whom he despises. To receive them he pretends to be terribly sick. The first is Signor Voltore (the 'vulture') who is a lawyer. Mosca assures him that he is Volpone's only heir. Then comes Corbaccio (the 'raven'), who is old and deaf and impatient. He offers some medecine that Mosca recognizes as a poison, then produces a bag of gold. Mosca says he will use it to excite Volpone to make a will in Corbaccio's favour, then suggests that Corbaccio should make a will naming Volpone his sole heir, in place of his son, as proof of his love. When the next client comes, Corvino the merchant (the 'crow'), Volpone seems to be at death's door, though he still has the strength to grasp a pearl and diamond Corvino has brought. Mosca invites his to shout insults at him, saying that he is quite unconscious, then suggests that they should suffocate Volpone with a pillow; this frightens Corvino, though he does not condemn Mosca for the idea. Finally, after mentioning the English visitor Lady Would-be, Mosca tells Volpone of the beauty of Corvino's young wife, who is jealously guarded. This makes Volpone long to see her.

Act Two begins with the play's sub-plot, that is often omitted in modern productions; the English traveller Sir Politic Would-be holds a conversation with another English traveller, Peregrine, showing himself to be vain and foolish. Volpone arrives disguised as a mountebank and begins a long speech boasting of the qualities of his special medicine. Corvino's wife, Celia, throws down some money from a window and Volpone tosses back his potion. Corvino suddenly appears and chases him away.

Volpone is love-struck and asks Mosca to get Celia for him. Meanwhile we see Corvino violently abusing his wife, mad with jealousy. Mosca arrives, saying that Volpone is a little better after using the mountebank's potion! The doctors, he says, have decided that he should have a young woman in bed with him, so that some of her energy may pass into him. Mosca says that one of the doctors offered his daughter, a virgin, sure that Volpone would not be able to harm her, and he urges Corvino to find someone first, since Volpone might change his will. Corvino decides to offer Celia!

Act Three begins with Mosca's praise of himself; the true parasite, he says, Is a most precious thing, droppped from above, Not bred 'mongst clods and clodpoles here on earth. I muse the mystery was not made a science, It is so liberally professed! Almost All the wise world is little else, in nature, But parasites or sub-parasites. He meets Corbaccio's son, Bonario, who belongs to a different universe; he is honest and frank, and despises Mosca. Mosca pretends to weep, and Bonario is at once touched with pity. Mosca then tells him that his father is making a will leaving everything to Volpone, disinheriting him! He offers to bring him to the place where it will be done.

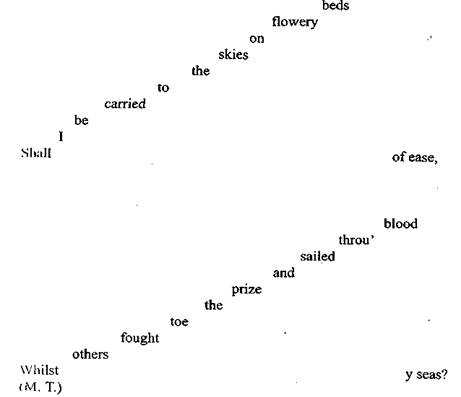

There follows an interview between Volpone and Lady Politic Would-be, who settles down and offers to make him some medecines. Volpone finds her a torment; Mosca arrives and urges her to leave quickly because he has just seen Sir Politic rowing off with a famous prostitute! As she leaves, he brings Bonario into the house, telling him to hide in a cupboard from where he will hear his father disinherit him. Then things become complicated, Corvino arrives with Celia, earlier than Mosca had expected them. He sends Bonario out into the corridor, while Corvino tells Celia why she is here. As a noble and faithful wife, she is horrified and begs him not to ask her to do such a thing. He insists, with horrible threats if she does not obey. At last Mosca drags him out, leaving Celia alone with Volpone who leaps from the bed, and begins to woo her, even singing an erotic carpe diem song:

Come, my Celia, let us prove, while we can, the sports of love;

Time will not be ours forever, he at length our good will sever;

Spend not then his gifts in vain. Suns that set may rise again;

But if once we lose this light, 'Tis with us perpetual night. Why should we defer our joys? Fame and rumour are but toys. Cannot we delude the eyes of a few poor household spies? Or his easier ears beguile, Thus removed by our wile? This no sin love's fruits to steal;

But the sweet theft to reveal, to be taken, to be seen, those have crimes accounted been.

Volpone is almost mad with desire, and begins to describe various kinds of erotic activities they could perform. She prays for pity, and when he seizes her, screams. Bonario rushes in to save her, and carries her off, wounding Mosca on the way. Volpone and Mosca are horrified, but Corbaccio's arrival gives Mosca an idea. He tells Corbaccio that Bonario has learned of his plan with the will and is threatening to kill him; Voltore has also come, unseen, and overhears Mosca being flattering to Corbaccio. He challenges him, and Mosca at once explains that he had planned that Bonario should kill his father, whose property would come to Volpone and so to Voltore. Voltore believes him; Mosca then says that Bonario has run off with Celia, intending to say that Volpone had tried to rape her so as to discredit him. Voltore decides to bring this matter to the judges, in order to stop Bonario.

Act Four begins with the continuation of the Sir Politic sub- plot; Lady Would-be thinks that Peregrine is the famous prostitute disguised and begins to scold him. Mosca comes and tells her that she is wrong, that the woman in question has been brought to the judges. The court scene begins. As the judges enter they are on the side of the young people, and order Volpone to be brought, although Mosca and the others assert he is too weak to move.

Voltore speaks, claiming that Celia and Bonario had long been lovers, that they had been caught, but forgiven by Corvino; that Corbaccio had decided to disown his son for his vice, and that Bonario had come to Volpone's house intending to kill his father. Unable to do so, he says, he attacked Volpone and Mosca, and resolved with Celia to accuse Volpone of rape. Corbaccio publicly rejects Bonario as his son, Corvino swears that his wife has cheated him with Bonario. Mosca supports their story with his wound. In addition, he claims to have seen Celia in the company of Sir Politic, and Lady Politic bursts in, claiming that she has seen them too!

The entry of Volpone, carried in apparently dying, seemingly quite unconscious and paralysed, is decisive for the judges. The two young people are arrested and Mosca sends away the hopeful clients, each of them convinced that Volpone's fortune is their's.

Act Five finds Volpone recovering from the strain. He orders his creatures to announce his death in the streets; then he makes a will in which Mosca is declared his heir and goes to hide behind a curtain, intending to watch the effect on each one. Voltore arrives first, as Mosca is busy making a list of goods; Corbaccio follows, then Corvino, and Lady Politic. Each is surprised to see the others. Volpone comments on their conduct in asides from behind the curtain. Mosca continues to write, then hands them the will, that they read together, although Corbaccio only finds Mosca's name a while later than the others. Mosca sends Lady Politic away first, then Corvino, Corbaccio, and finally Voltore, after giving to each a moralizing summary of their previous actions.

Volpone is delighted, wishes he could see their disappointment out on the streets. Mosca suggests that he disguise himself as a common sergeant. There is an interlude where Peregrine in disguise tells Sir Politic that he has been denounced as a foreign agent. Sir Politic decides to disguise himself in a huge turtle's shell; Peregrine brings in some merchants to admire the beast, and they torment Sir Politic. He decides to leave at once. Volpone dresses as a soldier, Mosca has put on a nobleman's dress; they plan to go walking in the streets, but Mosca tells us he plans to make Volpone share his fortune with him, and stays behind in control of the house. Volpone congratulates each of the clients on their good fortune, and enjoys their fury.

They are all going to the court, where Bonario and Celia are to be sentenced. Voltore suddenly begins to repent, and is about to tell the truth, it seems. He has written certain aspects of the truth in his notes. The others claim that he has been bewitched; news of Volpone's death supports their story. As Voltore is about to speak, the disguised Volpone whispers to him that Mosca wants him to know that in fact Volpone is not yet dead and that he is still the heir. Voltore pretends to collapse and Volpone declares that an evil spirit has just left him. He rises, and declares that Volpone is alive. Mosca comes in, and insists Volpone is dead. Meanwhile, Volpone has realized Mosca's plan against him; he tries to negociate in whispers, but Mosca rejects him and asks the judges to punish him.

In despair, Volpone throws off his disguise, and everything becomes clear; Bonario and Celia are freed, Mosca is condemned to be a 'perpetual prisoner in our galleys,' prison ships where no one survived long. All Volpone's fortune is confiscated to help the sick, and he is to stay in prison until he is 'sick and lame indeed.' Voltore is banished, Corbaccio sent to a monastery to die, Corvino will be rowed round Venice wearing ass's ears then put in the pillory, and Celia is returned to her family with three times her dowry.

Ben Jonson’s Volpone: black comedy from the dawn of the modern eraIn response to the Sydney Theatre Company’s (STC) production of Ben Jonson’s Volpone last year, I determined to undertake a study of the life and work of this extraordinary playwright and poet. Although his work is seldom performed these days, Jonson was one of the leading protagonists in the most vibrant period of early English theatre. For a time, he was considered the virtual Poet Laureate of England. His literary stature rivalled, and for the century after his death, even overshadowed that of Shakespeare.

Volpone is recognised as one of Jonson’s major works. Some 400 years after it was written, the play, about compulsive acquisitiveness and abuse of privilege, still resonates with its audience. The characters—or caricatures—remain recognisable, as does Jonson’s exposure of the pomposity of the legal system and the hypocrisy of wealthy lawyers who are prepared to argue anything for a price.

Understanding Jonson’s life and work proved to be more difficult than I imagined. Although much has been written on the subject, most of it divorces the playwright and his plays from their historical context in England and the wider social and political ferment that was underway in Europe. Jonson, like his literary creation Volpone, was very much larger than life. But he can be easily lost in an examination of the minutiae of his work.

I hope that in my preliminary investigations, I have managed to avoid this pitfall.

Ben Jonson’s Literary Activity

Jonson’s life story reads like a tragic novel. Born in London the posthumous son of a clergyman and trained by his stepfather as a bricklayer, Jonson became a mercenary, then an actor and leading playwright. At the height of his career, he was unchallenged in his chosen profession and a companion to some of the leading figures of his day. But he died virtually alone and impoverished eight years after suffering a debilitating stroke. He was buried beneath Westminster Abbey under the inscription “O Rare Ben Johnson”.

Jonson’s life spanned the years 1573 to 1637, a period of extraordinary change in English society: from the latter years of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I through to the eve of the English Civil War in 1642. Passionate and volatile, he was a man with a clear eye for the world around him. His plays are noted for their satirical view of the modern—capitalist—class relations that were beginning to develop.

Bourgeois monetary relations were breaking down the old feudal ties that had existed in England and which had been grounded in a largely subsistence agricultural economy. London was experiencing an explosive expansion—a process driven by the impact of trade and the early market economy. A century before Volpone was written, the city’s population numbered just 60,000. By the time of the play’s first performance in 1606, it had more than trebled to over 200,000. London was soon to become Europe’s largest city.

The growth continued despite bouts of the plague and other epidemics. In the years 1603 and 1625, for example, between one fifth and one quarter of the residents died from disease. One of Jonson’s later major works, The Alchemist, is set in London during an outbreak of the plague and concerns a wealthy home owner who has fled the capital, leaving the servants in charge of his city mansion.

The expansion of trade along the Thames, and the broadening power of the royal court led to a London property boom. England’s foreign trade, which extended from Russia to the Mediterranean and the New World, grew tenfold between 1610 and 1640.

Economic growth was also accompanied by deepening social inequality. The real wage of carpenters, for instance, halved from Elizabeth’s reign to that of Charles I. Side by side with opulent wealth were squalid tenements. Yet the poor from elsewhere in the country and from continental Europe were drawn to London by the prospect of wages that were more than 50 percent higher than the rest of southern England.

The city became a place of business and of fashion for the rural-based aristocracy, and Jonson parodies in some of his plays the tendency of young aristocrats to sell acres of their land to pay for city fineries. London was the heart of the royal court and the state bureaucracy. At any time over a thousand gentlemen connected with parliament or the law courts could be found residing at the city’s inns.

These inns became a hub of intellectual ferment where writers and actors like Jonson met with merchants, gentlemen and other leading figures of the day. Jonson dedicated his first major work, Every Man In His Humour, to these inns, calling them “the noblest nurseries of humanity and liberty in the kingdom”.

London’s economic expansion and the aggregation of so many and varied social elements stimulated the cultural development expressed in Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre. At the same time, the social tensions brewing within the growing metropolis created a receptive audience for the satire for which Jonson was to become famous.

The English theatre

Established theatre was still a relatively new phenomenon in sixteenth century England. The first permanent legal theatre was established up in London in 1552. Before that, performances were carried out on temporary platforms set up in taverns and inns. Entertainment at the new venues ranged from bear baiting to performances for the royal court.

Jonson was almost a generation younger than the major Elizabethan writers Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare who led the theatrical exploration of new aspects of the human experience. He records his appreciation of Shakespeare in a poem where he notes that “he was not of an age but for all time.”

The first mention of Jonson in the theatre comes in 1597 in a note for a four-pound loan given to him for his work as an actor by the entrepreneur William Henslowe. That same year Jonson was imprisoned for his part in writing a play called The Isle of Dogs, a satirical work mocking the Scots.

Released soon after, Jonson quickly became better known for his writing than his acting, producing works for the leading theatres of the day. Every Man in His Humour, finished in late 1598, established him as a major writer of comedy and satire. Its first performance was at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre.

But Jonson was again imprisoned, this time for killing an associate actor in a duel. He was acquitted only after successfully pleading “benefit of clergy”—a law allowing for the pardoning of defendants due to their literacy.

Jonson was one of the most educated writers of the day. He had a profound knowledge of Latin and Greek theatre and poetry and, like many artists of the period, he developed his work within the framework established by the classics. In all the arts and sciences, the heritage of Greece and Rome was being rediscovered and re-assimilated.

The English Renaissance writers reworked classical, traditional and contemporary stories. Shakespeare, for example, reworked an already rephrased English translation of an Italian story for his Romeo and Juliet (1595), which the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega retold as a tragicomedy in 1608. Christopher Marlowe’s epic poem Hero and Leander, which is based on an ancient Greek myth, says more about the customs of contemporary England than of the ancient Greeks. The art was in the telling, not in the creation, of the stories.

Jonson is often accused of being constricted in his writing by classical references. But he was in no way overawed by the classics. In fact, part of his creative genius was his ability to rework themes and ideas to fit the contemporary setting. Many of the sources were so seamlessly integrated into his stories that only after centuries of scholarship were the connections established between his work and that of earlier writers.

He drew directly on ancient mythology in his masques for the royal court. Masques were highly stylised theatrical events performed for and by the members of the aristocracy. With Jonson and his sometime collaborator, architect Inigo Jones, the masque developed from a relatively simplistic entertainment into an elaborate (although rather self indulgent and hugely expensive) art form.

The playwright was also influenced by European theatre, particularly the Italian Commedia dell’arte. Commedia dell’arte troupes had toured London in the late 1590s and a number of the characters in Volpone have their direct counterparts in this Italian theatrical form. Jonson’s Volpone, for example, fits well within the range of the Commedia’s Pantalone, whose character ranged from a miserly and ineffectual old man to an energetic cuckolder with “almost animal ferocity and agility”. In the play, Jonson integrates this influence with classical references, as well as English and European folk mythology and theatrical styles.

Jonson also drew on the English tradition of medieval morality plays, where actors personified human characteristics such as Virtue, Vice, Lechery or Curiosity to illustrate moral lessons. The plots were generally limited, since the moral points were universal rather than specific.

Jonson welded all these influences into a theatre that was purposeful and aimed at playing a critical role in society. His comedies brought a new realism as well as a sharp eye for outlining human character types. As one writer commented, he gave “a new sense of the interdependence of character and society”.

While Volpone was set in Venice, London audiences were well able to recognise its themes. For his realism, Jonson was attacked at the time as “a meere Empyrick, one that gets what he hath by observation”. But four centuries on, his ability to capture social contradictions and present them in a captivating form continues to resonate.

Through the play, considered by some his masterpiece, Jonson portrays with a black humour a society in which the pursuit of wealth and individual self-interest have become primary. Venice was regarded as the epitome of a sophisticated commercial city and virtually all the characters are revealed as corrupt or compromised.

Volpone means “fox” in Italian. Jonson based his story around medieval and Aesopian tales in which a fox pretends to be dead in order to catch the carrion birds that come to feed on its carcass. In the play, Volpone is a single and aging Venetian “magnifico” who has devised a trick to fleece his neighbours while simultaneously nourishing his sense of superiority over his hapless victims. For three years he has pretended to be dying, so as to encourage legacy hunters to bring gifts in the hope of being named as his beneficiary.

With the aid of his servant Mosca, Volpone strings along his suitors—Voltore, Corbaccio and Corvino—extracting their wealth by feeding their avarice. (Voltore Corbaccio and Corvino are the Italian names for vulture, crow and raven.) Voltore, a lawyer, offers Volpone a platter made of precious metal. Corbaccio, a doddering gentleman, is talked into disinheriting his son Bonario in favour of Volpone, while Corvino, a miserly merchant and hugely jealous husband, is driven by greed to offer his young wife Celia to bed and comfort the supposedly dying Volpone.

Here Volpone, a rogue whose victims trap themselves by their own weaknesses (and are therefore deserving of their respective fates) becomes overwhelmed by his own passions. Definitely not at death’s door and completely obsessed, he tries to force himself onto Celia and is only stopped by the lucky appearance of Bonario. The two innocents bring charges in court against the old man. But countercharges of adultery and fornication against Celia and Bonario are laid by the three legacy hunters who are desperate to defend what each considers his own future wealth.

Volpone revels in these ever-widening displays of degradation. He decides to stage his own death so he can witness their frenzy when they see him bequeathing his wealth to Mosca. However, after Mosca begins preparing the elaborate funeral, he ceases to acknowledge his former master. As the heir to Volpone’s great wealth, Mosca is transformed in the eyes of the courtroom judges—who are as self-serving as the rest—from a lowly servant into an eligible young man to whom they might marry their daughters.

Desperate not to be outfoxed by his servant, Volpone reveals himself, thus exposing his own and everyone else’s guilt. He is stripped of his wealth, which is given to charity, and sentenced to prison, while Mosca is condemned to the galleys for passing himself off as a person of breeding. Voltore, the advocate, is debarred from the court and Corbaccio’s wealth is transferred to his son Bonario. Corvino is paraded through Venice as an ass, while his wife Celia is sent home to her family with triple her dowry.

Jonson skillfully manipulates the audience so that it identifies with Volpone and his brazen schemes. The old magnifico’s zest is infective and the audience is swept along with his machinations only to find itself, along with the anti-hero, hovering at the edge of criminality. In this way, the author tries to confront us with the dangers of unrestrained self-interest and with what Jonson considers to be a necessary sense of social responsibility.

Genre: Comic drama, but also a satire.

Form: blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter) mixed with comic song. Since the "plot" is a low criminal conspiracy (but what was the rebellion against Henry IV or Lear?), the "subplot" is a parody of criminal conspiracy set in Venice but involving an English traveler, an English nobleman and his wife, all of whom are on tour.

Characters and Summary: This plot closely parallels Horace's satire on legacy hunters (Book II.7) but dramatizes it with characters whose flattened, comic/satiric personas represent various types of human personality as they are distorted by greed, lust, and sheer perversity. Jonson alerts us to the symbolic order of the action's meaning by means of the names he assigns the primary characters: Volpone (fox--deceiver), Mosca (fly--parasite), Voltore (vulture--scavenger/lawyer), Corbaccio (crow--wealthy but still greedy man), and Corvino (raven, another scavenger--the wealthy merchant who can't get enough). These characters all seek to be named Volpone's heir in order to gain his treasure, but they offer him gifts to achieve that honor, and he (though nowhere near death) strings them along, more in love with his delight in deceiving them than even his beloved gold. A love plot is attached to this legacy-hunt, involving Corvino's wife (Celia) and Corbaccio's son (Bonario), but one of the play's puzzles is that they are such relatively lifeless, though moral, characters. Below these levels, three more sets of characters populate the stage. Nano (a dwarf), Castrone (an eunuch), and Androgyno (a hermaphrodite) join Mosca as Volpone's courtiers, Sir Poltic Would-be and his wife are deceived by Peregrine (the young English man on the Continental tour), and the elders of Venice alternately try to profit from and to bring justice to the confusion (Commendatori [sheriffs], Mercatori [merchants], Avocatori [lawyers, brothers of Corvino], and Notario [the court's registrar]).

So the plot, in brief, is that the conspirators try to deceive Volpone, but he's really deceiving them, until his agent (Mosca) deceives him (and them) and they bring him to the court, which they all try to deceive, until they are unmasked (while Peregrine is being deceived by and deceiving Sir and Lady Politic Would-be). Got it?

Ïîõîæèå ðàáîòû

... the guises provided by their respective archetypes. The “Daughter”/“Niece” Binary in As You Like It The “daughter” and “niece” archetypes, of course, are not universally applicable to all women in Shakespeare’s comedies. In As You Like It, there are other female characters which defy such classification. Phoebe, for example, exhibits traits of both “niece” (in her willful pursuit of the ...

... role in his decision to move to London's theatre scene. In fact, during the late 1580s and early 1590s, Shakespeare travelled back and forth between London and Stratford-on-Avon, but by this time, the momentum of Shakespeare's life was toward his career and away from family, hearth, and home. Although we lack hard facts, we may surmise that before he took up a career as a playwright, Shakespeare ...

... texts were available. Subsequently Henry V (1600) was pirated, and Much Ado About Nothing was printed from "foul papers"; As You Like It did not appear in print until it was included in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories & Tragedies, published in folio (the reference is to the size of page) by a syndicate in 1623 (later editions appearing in 1632 and 1663). The only precedent for ...

of promoting a morpheme is its repetition. Both root and affixational morphemes can be emphasized through repetition. Especially vividly it is observed in the repetition of affixational morphemes which normally carry the main weight of the structural and not of the denotational significance. When repeated, they come into the focus of attention and stress either their logical meaning (e.g. that of ...

0 êîììåíòàðèåâ