Íàâèãàöèÿ

Language is a workable system of sygnals, that is linguistic forms by means of which people communicate

1. Language is a workable system of sygnals, that is linguistic forms by means of which people communicate.

2. Grammar is a meaningful arrangement of linguistic forms from morphemes to sentence.

The chief contribution of the American Descriptive School to modern linguistics is the elaboration of the techniques of linguistic analysis. The main methods are the Distributional method and the method of Immediate Constituents.

A recent development of Descriptive linguistics gave rise to a new method – the Transformational grammar. The TG was first suggested by Zellig S. Harris as a method of analyzing the ”raw meterial” (concrete utterances) and was later elaborated by Noam Chomsky as a synthetic method of ”generating” (constructing) sentences. The TG refers to syntax only and presupposes the recognition (identification) of such linguistic units as phonemes, morphemes and form-classes, the latter being stated according to the distributional and the IC-analysis or otherwise. Charles Carpenter Fries is another prominent figure of American linguistic theory. His main work ”The Structure of English” is widely known.

Theme 1. INTRODUCTION (continued).

Point 5. Problems of ’Case’ Grammar.

’Case” Grammar, or role grammar, is a method to describe the semantics of a sentence, without modal or performative elements, as a system of semantic valencies through the bonds of ’the main verb’ with the roles prompted by its meaning and performed by nominal components.

Example: the verb ’to give’ requires the roles, or cases, of the agent, the receiver and the object of giving.

He gives me a book. I am given a book by him. A book is given to me by him.

Case Grammar emerged within the frames of Transformational Grammar in the late 1960s and developed as a grammatical method of description.

There are different approaches towards Case Grammar concerning the type of the logical structure of the sentence, the arrangement of roles and their possible combinations, i.e. ’case frames’, as well as the way in which semantic ties are reflected in a sentence structure by means of formal devices.

Case Grammar has been used to describe many languages on the semantic level. The results of this research are being used in developing ’artificial intellect’ (the so-called ’frame semantics’) and in psycholinguistics.

However, Case Grammar has neither clear definitions nor criteria to identify semantic roles; their status is vague in the sentence derivation; equally vague are the extent of fulness of their arrangement and the boundaries between ’role’ elements and other elements in a sentence.

Point 6. The main conceptions of syntactic semantics (or semantic syntax) and text linguistics

The purpose and the social essence of language are to serve as means of communication. Both structure and semantics of language ultimately serve exactly this purpose. For centuries linguists have focused mainly on structural peculiarities of languages. This may be easily explained by the fact that structural differences between languages are much more evident than differences in contents; that is why the study of the latter was seen as research in concrete languages. The correctness of such an assumption is proved by the fact that of all semantic phenomena the most studied were those most ideoethnic, for example, lexical and semantic structure of words. As for syntactic semantics, which is in many aspects common for various languages, it turned out to be least studied. Meanwhile, the study of this field of language semantics is of special interest for at least two reasons. Firstly, communication is not organized by means of separate words, but by means of utterances, or sentences. Learning speech communication, fully conveyed with the help of language information, is impossible without studying sentence semantics. Secondly, studying the semantic aspect of syntactic constructions is important, besides purely linguistic tasks, for understanding the peculiarities and laws of man’s thinking activities. Language and speech are the basic source of information which is a foundation for establishing the laws, as well as the categories and forms, of human thinking. Thus, language semantics is as important and legal object of linguistic study as language forms are.

Point 7. Modern methods of grammatical analysis: the I.C. method (method of immediate constituents), the oppositional, transformational and componential methods of analysis.

(a) The IC method, introduced by American descriptivists, presents the sentence not as a linear succession of words but as a hierarchy of its ICs, as a ’structure of structures’.

Ch. Fries, who further developed the method proposed by L.Bloomfield, suggested the following diagram for the analysis of the sentence which also brings forth the mechanism of generating sentences: the largest IC of a simple sentence are the NP (noun phrase) and the VP (verb phrase), and they are further divided if their structure allows.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Layer 3 The recommending committee approved his promotion.

Layer 3 The recommending committee approved his promotion.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Layer 2

Layer 2

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Layer 1

Layer 1

The deeper the layer of the phrase (the greater its number), the smaller the phrase, and the smaller its ICs. The resulting units (elements) are called ultimate constituents (on the level of syntax they are words). If the sentence is complex, the largest ICs are the sentences included into the complex construction.

The diagram may be drawn somewhat differently without changing its principle of analysis. This new diagram is called a ‘candelabra’ diagram.

The man hit the ball.

| ||||||||

S

If we turn the analytical (‘candelabra’) diagram upside down we get a new diagram which is called a ‘derivation tree’, because it is fit not only to analyze sentences, but shows how a sentence is derived, or generated, from the ICs.

The IC model is a complete and exact theory but its sphere of application is limited to generating only simple sentences. It also has some demerits which make it less strong than transformational models, for instance, in case of the infinitive which is a tricky thing in English.

(b) The oppositional method of analysis was introduced by the Prague School. It is especially suitable for describing morphological categories. The most general case is that of the general system of tense-forms of the English verb. In the binary opposition ‘present::past’ the second member is characterized by specific formal features – either the suffix -ed, or a phonemic modification of the root. The past is thus a marked member of the opposition as against the present, which is unmarked.

The obvious opposition within the category of voice is that between active and passive; the passive voice is the marked member of the opposition: its characteristic is the pattern 'be+Participle II', whereas the active voice is unmarked.

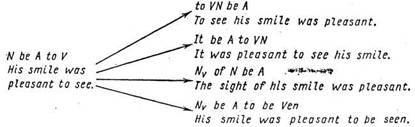

(c) The transformational method of analysis was introduced by American descriptivists Z.Harris and N.Chomsky. It deals with the deep structure of the utterance which is the sphere of covert (concealed) syntactic relations, as opposed to the surface structure which is the sphere of overt relations that manifest themselves through the form of single sentences. For example: John ran. She wrote a letter.

But: 1) She made him a good wife.

2) She made him a good husband.

The surface structures of these two sentences are identical but the syntactic meanings are different, and it is only with the help of certain changes (transformations) that the covert relations are brought out:

1) She became a good wife for him.

2) He became a good husband because she made him one.

The transformational sentence model is, in fact, the extension of the linguistic notion of derivation to the syntactic level which presupposes setting off the so-called ‘basic’ or ‘kernel’ structures and their transforms, i.e. sentence-structures derived from the basic ones according to the transformational rules.

E.g. He wrote a letter. – The letter was written by him.

This analysis helps one to find out difference in meaning when no other method can give results, it appears strong enough in some structures with the infinitive in which the ICs are the same:

1) John is easy to please.

2) John is eager to please.

![]()

![]()

![]() 1) It is easy - - It is easy (for smb.) to please John

1) It is easy - - It is easy (for smb.) to please John

![]()

![]() Smb. pleases John - - John is easy to please.

Smb. pleases John - - John is easy to please.

![]() 2) John is eager - -

2) John is eager - -

![]() John is eager to please.

John is eager to please.

John pleases smb. - -

(d) The componential analysis belongs to the sphere of traditional grammar and essentially consists of ‘parsing’, i.e. sentence-member analysis that is often based on the distributional qualities of different parts of speech, which sometimes leads to confusion.

E.g. My friend received a letter yesterday. (A+S+P+O+AM)

His task is to watch. (A+S+V(+?)

His task is to settle all matters. (A+S+V+?+A+O)

Theme 2. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STRUCTURE

OF MODERN ENGLISH.

Point 1. The correlation of analysis and synthesis in the structure of English.

Languages may be synthetical and analytical according to their grammatical structure.

In synthetical languages, such as, for instance, Ukrainian, the grammatical relations between words are expressed by means of inflexions: e.g. äîëîíü ðóêè.

In analytical languages, such as English, the grammatical relations between words are expressed by means of form-words and word order: e.g. the palm of the hand.

Analytical forms are mostly proper to verbs. An analytical verb-form consists of one or more form-words, which have no lexical meaning and only express one or more of the grammatical categories of person, number, tense, aspect, voice, mood, and one notional word, generally an infinitive or a participle: e.g. He has come. I am reading.

However, the structure of a language is never purely synthetic or purely analytical. Accordingly in the English language there are:

1. Endings (speaks, tables, brother’s, smoked).

2. Inner flexions (man – men, speak – spoke).

3. The synthetic forms of the Subjunctive Mood: were, be, have, etc.

Owing to the scarcity of synthetic forms the order of words, which is fixed in English, acquires extreme importance: The fisherman caught a fish.

A deviation from the general principle of word order is possible only in special cases.

Point 2. Peculiarities of the structure of English in the field of accidence (word-building and word-changing).

Affixes, i.e. prefixes and suffixes, in the English language have a dual designation – some are used in word-building, others – in word-changing. Word-building is derivation of new words from basic forms of some part of speech. Word-changing is derivation of different forms of the same word. Word-building and word-changing have their own sets of affixes: their coincidence may only be pure accidental homonymy (cf.=confer –er in agentive nouns – writer, and –er in the comparative degree of adjectives – longer). There may be occasional cases of a word-changing suffix transformation into a word-building one: I am in a strong position to know of her doings.

English prefixes perform only word-building functions, and are not supposed to be considered in this course. As for suffixes, they are divided into word-building and word-changing ones; the latter are directly related to the grammatical structure.

Point 3. Peculiarities of the English language in the field of syntax.

English syntax is characterized by the following main features:

1) A fixed word order in the sentence;

2) A great variety of word-combinations;

3) An extensive use of substitutes which save the repetition of a word in certain conditions (one, that, do);

4) Availability of numerous form-words to express the grammatical relations between words in the sentence or within the word-combination;

5) Plentiful grammatical constructions.

Point 4. Functional and semantic connection of lexicon and grammar.

The functional criterion of word division into parts of speech presupposes revealing their syntactic properties in the sentence. For notional words, it is primarily their position-and-member characteristics, i.e. their ability to perform the function of independent members of the sentence: subject, verbal predicate, predicative, object, attribute, adverbial modifier. In defining the subclass appurtenance of words, which is the second stage of classification, an important place is occupied by finding out their combinability characteristics (cf., for example, the division of verbs into valency subclasses). This is the level of analysis where a possible contradiction between substantive and lexical, and between categorial and grammatical, semantics of the word, is settled. Thus, in its basic substantive semantics the word ‘stone’ is a noun, but in the sentence ‘Aunt Emma was stoning cherries for preserves’ the said substantive base comes forward as a productive one in the verb. However, the situational semantics of the sentence reflects the stable substantive orientation of the lexeme, retained in the causative character of its content (here, ‘to take out stones’). The categorial characteristics of such lexemes might be called ‘combined objective and processional’ one. Unlike this one, the categorial characteristics of the lexeme ‘go’ in the utterance ‘That’s a go’ will be defined as ‘combined processional and objective’. Still, the combined character of semantics on the derivational and situational, and on the sensical level, does not deprive the lexeme of its unambiguous functional and semantic characterization by class appurtenance.

Point 5. Functional and semantic (lexico-grammatical) fields.

The idea of field structure in the distribution of relevant properties of objects is applied in the notion of the part of speech: within the framework of a certain part of speech a central group of words is distinguished, which costitutes the class in strict conformity with its established features, and a peripheral group of words is set off, with the corresponding gradation of features. On the functional level, one and the same part of speech may perform different functions.

Theme 3. ACCIDENCE.

Point 1. The main notions of accidence.

Accidence is the section of grammar that studies the word form. In this study it deals with such basic notions as ‘the word’, ‘the morpheme’, ‘the morph’, ‘the allomorph’, ‘the grammatical form and category of the word’, as well as its ‘grammatical meaning’, and also ‘the paradigm’, ‘the oppositional relations and the functional relations of grammatical forms’.

Point 2. The notion of the morpheme. Types of morphemes. Morphs and

allomorphs

(a) One of the most widely used definitions of the morpheme is like this: ‘The morpheme is the smallest linear meaningful unit having a sound expression’. However, there are other definitions:

- L.Bloomfield: The morpheme is ‘a linguistic form which bears no partial resemblance to any other form’.

- B. De Courtenay: The morpheme is a generalized name for linear components of the word, i.e. the root and affixes.

- Prof. A.I.Smirnitsky: The morpheme is the smallest language unit possessing essential features of language, i.e. having both external (sound) and internal (notional) aspects.

(b) Morphemes, as it has been mentioned above, may include roots and affixes. Hence, the main types of morphemes are the root morpheme and the affix morpheme. There also exists the concept of the zero morpheme for the word-forms that have no ending but are capable of taking one in the other forms of the same category, which is not quite true for English.

As for the affix morpheme, it may include either a prefix or a suffix, or both. Since prefixes and many suffixes in English are used for word-building, they are not considered in theoretical grammar. It deals only with word-changing morphemes, sometimes called auxiliary or functional morphemes.

(c) An allomorph is a variant of a morpheme which occurs in certain environments. Thus a morpheme is a group of one or more allomorphs, or morphs.

The allomorphs of a certain morpheme may coincide absolutely in sound form, e.g. the root morpheme in ‘fresh’, ‘refreshment’, ‘freshen’, the suffixes in ‘speaker’, ‘actor’, the adverbial suffix in ‘greatly’, ‘early’. However, very often allomorphs are not absolutely identical, e.g. the root morpheme in ‘come-came’, ‘man-men’, the suffixes in ‘walked’, ‘dreamed’, ‘loaded’.

Point 3. The grammatical form of the word. Synthetical and analytical forms.

(a) The grammatical form of the word is determined by its formal features conveying some grammatical meaning. The formal feature (flexion, function word, etc.) is the ‘exponent’ of the form, or the grammatical ‘formant’, the grammatical form proper being materialized by the unification of the stem with the formant in the composition of a certain paradigmatic row. Therefore, the grammatical form unites a whole class of words, each expressing a corresponding general meaning in the framework of its own concrete meaning. (E.g. the plural form of nouns: books-dogs-cases-men-oxen-data-radii, etc.) Thus the grammatical form of the word reflects its division according to the expression of a certain grammatical meaning.

(b) Synthetic forms are those which materialize the grammatical meaning through the inner morphemic composition of the word. Analytical forms, as opposed to synthetic ones, are defined as those which materialize the grammatical meaning by combining the ‘substance’ word with the ‘function’ word.

Theme 3. ACCIDENCE (continued).

Point 4. The grammatical category.

The grammatical category is a combination of two or more grammatical forms opposed or correlated by their grammatical meaning. A certain grammatical meaning is fixed in a certain set of forms. No grammatical category can exist without permanent formal features. Any grammatical category must include as many as two contrasted forms, but their number may be greater. For instance, thre are three tense forms – Present, Past and Future, four aspect forms – Indefinite, Perfect, Continuous, Perfect Continuous, but there are only two number forms of nouns, two voices, etc.

Point 5. The grammatical meaning. Categorial and non-categorial meanings in grammar.

(a) The grammatical meaning is a generalized and rather abstract meaning uniting large groups of words, being expressed through its inherent formal features or, in an opposition, through the absence of such. Its very important property is that the grammatical meaning is not named in the word, e.g. countables-uncountables in nouns, verbs of instant actions in Continuous (was jumping, was winking), etc.

The grammatical meaning in morphology is conveyed by means of:

1. Flexion, i.e. a word-changing formant which may be outer (streets, approached) or inner (foot-feet, find-found).

2. Suppletive word forms (to be-am-was, good-better-best).

3. Analytical forms (is coming, has asked).

(b) The most general meanings conveyed by language and finding expression in the systemic, regular correlation of forms, are thought of as categorial grammatical meanings. Therefore, we may speak of the categorial grammatical meanings of number and case in nouns; person, number, tense, aspect, voice and mood in verbs, etc. Non-categorial grammatical meanings are those which do not occur in oppositions,e.g. the grammatical meanings of collectiveness in nouns, qualitativeness in adjectives, or transitiveness in verbs, etc.

Point 6. The notion of the paradigm in morphology.

An orderly combination of grammatical forms expressing a certain categorial function (or meaning) constitutes a grammatical paradigm. Consequently, a grammatical category is built up as a combination of respective paradigms (e.g. the category of number in nouns, the category of tense in verbs, etc.).

Point 7. Oppositional relations of grammatical forms.

The basic method of the use of oppositions was elaborated by the Prague School linguists. In fact, the term ‘opposition’ should imply two contrasted elements, or forms, i.e. the opposition should be binary. The principle of binary oppositions is especially suitable for describing morphological categories where this kind of relations is more evident.

For example, the tense-forms of the English verb may be divided into two halves: the forms of the present plane and those of the past. The former comprises the Present, Present Perfect, Present Continuous, Present Perfect Continuous, and the Future; the latter includes the Past, Past Perfect, Past Continuous, Past Perfect Continuous, and the Future-in-the-Past. The second half is characterized by specific formal features – either the suffix –ed (or its equivalents) appear, or a phonemic modification of the root. The past is thus a marked member of the opposition ‘present::past’ as against the present sub-system, which is the unmarked member. The same may be applied to perfect and non-perfect forms, active and passive forms, singular and plural forms in class nouns, etc.

Point 8. Functional transpositions of grammatical (morphological) forms.

In context functioning of grammatical forms under real circumstances of communicating, their oppositional categorial features interact so that a member of the categorial opposition may be used in a position typical of the other contrasted member. This phenomenon is referred to as the functional transposition. One must bear in mind that there are two kinds of functional transpositions: the one with a partial loss of the functional property, and the one with a complete loss of the functional property. The former may also be defined as the functional transposition proper where the substituting member performs the two functions simultaneously. E.g. the unusual usage of the plural form of a ‘unique’ object (cf.: …’that skin so prized by Southern women and so carefully guarded with bonnets, veils and mittens against hot Georgian suns’. (M.Mitchel)

Point 9. Neutralization of the opposition.

The second kind of functional transposition where the substituting member completely loses its functional property, is the actual neutralization of the opposition. Such neutralization itself does not possess any expressive meaning but is generally related to the variations of particular meanings (cf.: A man can die but once.(proverb) The lion is not so fierce as he is painted.(proverb)

Point 10. Polysemy, synonymy and homonymy in morphology.

Morphological polysemy implies representations of a word as different parts of speech, e.g. the word ‘but’ may function as a conjunction (last, but not least), a preposition (there was nothing but firelight), a restrictive adverb (those words were but excuses), a relative pronoun (there are none but do much the same), a noun in the singular and plural (that was a large but; his repeated buts are really trying).

Morphological synonymy reflects a variety of representations by different parts of speech for the same meaning, e.g. due to (adjective), thanks to (noun), because of (preposition), etc.

Morphological homonymy may be described as phonetic equivalents with different grammatical functions, e.g. He looks – her looks; they wanted – the job wanted; smoking is harmful – a smoking man; you read – we saw you, etc.

Point 11. The main problems of functional morphology.

The problems of functional morphology are many, the main and most disputed being:

(a) the functions of ‘formal’ morphemes (affixes) and allomorphs;

(b) the functional correlation, i.e. connection of phenomena differing in certain features but united through others (import-to import, must-should);

(c) the functional classification of words as parts of speech.

Theme 4. THE PARTS OF SPEECH.

Point 1. The problems of the parts of speech.

The whole lexicon of the English language, like the one of all Indo-European languages, is divided into certain lexico-grammatical classes traditionally called ‘parts of speech’. The existence of such classes is not doubted by any linguists though they might have different points of view as to their interpretation. Classification of the parts of speech is still a matter of dispute; linguists’ opinions differ concerning the number and the names of the parts of speech.

Point 2. The principles of division into the parts of speech. Issues of discussion in the classification of words into the parts of speech. Notional and functional parts of speech. Conversion of the parts of speech.

(a) The main principles of word division into certain groups, that had long existed, were formulated by L.V.Shcherba quite explicitly. They are lexical meaning, morphological form and syntactic functioning. Still, some classifications are based on some of the three features, for any of them may coincide neglecting the strict logical rules.

(b) In linguistics there have been a number of attempts to build up such a classification of the parts of speech (lexico-grammatical classes) that would meet the main requirement of a logical classification, i.e. would be based on a single principle. Those attempts have failed.

H.Sweet, the author of the first scientific grammar of the English language, divides the parts of speech into two main groups – the declinables and the indeclinables. That means that he considers morphological properties to be the main principle of classification. Inside the group of the declinables he kept to the traditional division into nouns, adjectives and verbs. Adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections are united into the group of the indeclinables. However, alongside of this classification, Sweet proposes grouping based on the syntactic functioning of certain classes of words. This leads to including nouns, pronouns, infinitives, gerunds and some other parts of speech into the same class, which is incorrect.

The Danish linguist O.Jespersen suggested the so-called theory of three ranks (primary, secondary and tertiary words), e.g. ‘furiously barking dog’ where ‘dog’ is a primary word, ‘barking’ – secondary, and ‘furiously’ – tertiary.

Another attempt to find a single principle of classification was made by Ch.Fries in his book ‘The Structure of English’. He rejects the traditional classification and tries to draw up a class system based on the word’s position in the sentence; his four classes correspond to what is traditionally called nouns (class 1), verbs (class 2), adjectives (class 3) and adverbs (class 4). Besides the four classes he set off 15 groups. And yet, his attempt turned out to be a failure, too, for the classes and groups overlap one another.

(c) Words on the semantic (meaningful) level of classification are divided into notional and functional.

To the notional parts of speech of the English language belong the noun, the adjective, the numeral, the pronoun, the verb and the adverb.

Contrasted against the notional parts of speech are words of incomplete nominative meaning and non-self-dependent, mediatory functions in the sentence. These are functional parts of speech. To the basic functional series of words in English belong the article, the preposition, the conjunction, the particle, the modal word, the interjection.

(d) From the point of view of their functional characteristics lexical units may belong to different lexico-grammatical classes. This kind of syntactic transition is called conversion and represents a widespread phenomenon as one of the most productive and economical means of syntactic transpositions. E.g. She used to comb her hair lovingly. – Here is your comb. They lived up north a few years ago. – You must be ready to take all these ups and downs easy.

Theme 4. THE PARTS OF SPEECH (continued).

Point 3. The parts of speech in the onomasiologic light.

Comparing the class division of the lexicon at the angle of functional designation of words, we first of all note a sharp contrast in language of two polar types of lexemes, the notional type and the functional one. Being evaluated from the informative-functional point of view, the polar distribution of words into completely meaningful and incompletely meaningful domains appears quite clear and fundamental; the overt character of the notional lexical system and the covert one of the functional lexical system (with the field of transition from the former to the latter being available) acquire the status of the most important general feature of the form.

The notional domain of lexicon is divided into four generalizing classes, not a single more or less. The four notional parts of speech defined as the words with a self-dependent denotational-naming function, are the noun (substantially represented denotations), the verb (processually represented denotations), the adjective (feature-represented denotations of the substantial appurtenance) and the adverb (feature-represented denotations of the non-substantial appurtenance).

However, the typical functional positions of these classes may be occupied by representatives of the functional classes by virtue of substitution, that is why some scholars speak of additional notional subclasses.

Point 4. The field nature of the parts of speech.

The intricate correlations of units within each part of speech are reflected in the theory of the morphological fields which states the following: every part of speech comprises units fully possessing all features of the given part of speech; these are its nucleus. Yet, there are units which do not possess all features of the given part of speech though they belong to it. Therefore, the field includes both central and peripheral elements; it is not homogeneous in composition (cf.: ‘gives’ – the lexical meaning of a process, the functional position of a predicate, the word-changing paradigm; and ‘must’ – a feeble lexical meaning, the functional position of a predicative, absence of word-changing paradigm).

Theme 5. THE NOTIONAL PARTS OF SPEECH.

Point 1. The noun. The grammatical meaning of the noun. Semantic and grammatical subclasses of nouns. Grammatical categories of the noun. The category of number. The correlation of the singular and the plural forms. The category of case. The varying semantics of the noun in the possessive case. Syntactic functions of nouns. The field structure of the noun.

(a) The noun is a notional part of speech possessing the meaning of substantivity.

(b) Substantivity is the grammatical meaning due to which word units, both the names of objects proper and non-objects, such as abstract notions, actions, properties, etc., function in language like the names of objects proper.

(c) From the point of view of semantic and grammatical properties all English nouns fall under two classes: proper nouns and common nouns.

Proper nouns are individual names given to separate persons or things. As regards their meaning proper nouns may be personal names (Mary, Peter, Shakespeare), geographical names (London, The Crimea), the names of the months and the days of the week, names of ships, hotels, clubs, etc. A large number of nouns now proper were originally common nouns (Brown, Smith, Mason). Proper nouns may change their meaning and become common nouns (sandwich, champagne).

Common nouns are names that can be applied to any individual of a class of persons or things (man, dog, book), collections of similar individuals or things regarded as a single unit (peasantry, family), materials (snow, iron,cotton) or abstract notions (kindness, development).

Thus there are different groups of common nouns: class nouns, collective nouns, nouns of material and abstract nouns.

Nouns may also be classified from another point of view: nouns denoting things (the word ‘thing’ is used in a broad sense) that can be counted are called countable nouns; nouns denoting things that cannot be counted are called uncountable nouns.

(d) We may speak of three grammatical categories of the noun.

Ïîõîæèå ðàáîòû

... clear and lucid language. There are some problems which are debated up to now, for example, «the reality of the perfective progressive». 1.3 The analysis of the stylistic potential of tense-aspect verbal forms in modern English by home linguists N.N. Rayevska [3; 30] is a well-known Ukrainian (Kiev) scholar who specialized in the study of English language and wrote two monographs: 1. The ...

... complications can be combined: Moira seemed not to be able to move. (D. Lessing) The first words may be more difficult to memorise than later ones. (K. L. Pike) C H A P T E R II The ways and problems of translating predicate from English into Uzbek. 1.2 The link-verbs in English and their translation into Uzbek and Russian In shaping the predicate the differences of language systems ...

... "compound" sentence, the combination of two or more syntactically independent, though semantically connected sentences, was analysed as a single sentence. The new terms, which were probably intended to improve the theory, became very popular in prescriptive grammar and, as we shall see, influenced some scientific grammars. Classical Scientific English Grammar in the Modern Period. The founders of ...

... of this language and changes in its synonymic groups. It has been mentioned that when borrowed words were identical in meaning with those already in English the adopted word very often displaced the native word. In most cases, however, the borrowed words and synonymous native words (or words borrowed earlier) remained in the language, becoming more or less differentiated in meaning and use. As a ...

0 êîììåíòàðèåâ