Навигация

Lexico-semantic characteristics of business letter correspondence

Курсовая работа

Сдала студентка гр. РП -41 Юрченко М. В.

ANNOTATION

The subject matter of the course paper is the role of lexics and semantics in the case of business letter correspondence. The question of the history of official communication, the main stages of business transactions, the role of person’s feeling for the proper use of phrases as well as his knowledge of grammar are highlighted. Moreover, those phrases which are more often used in business letters are examined from the point of view of their appropriateness in different situations. The practical part contains several examples of business letters; the occasions on which they were written and some of their characteristics are observed.

INTRODUCTION

Letter writing - is an essential part of communication, an intimate part of experience. Each letter-writer has a characteristic way of writing, his style of writing, his way of expressing thoughts, facts, etc. but it must be emphasised that the routine of the official or semi-official business letters requires certain accepted idioms, phrases, patterns, and grammar which are found in general use today. Therefore certain skills must be acquired by practice, and details of writing must be carefully and thoroughly learnt.

A cheque, a contract or any other business paper sent by mail should always be accompanied by a letter. The letter says what is being sent so that the recipient should know exactly what you intended to send. It is a typical business letter which some people call "routine". The letter may be short or long, it may contain some very important and much less important information - every letter requires careful planning and thoughtful writing.

In recent years English has become a universal business language. As such, it is potentially an instrument of order and clarity. But words and phrases have unexpected ways of creating binding commitments.

Letter-writing, certainly, is not the same as casual conversation, it bears only the same power of thoughts, reflections, and observations as in conversational talk, but the form may be quite different. What makes the letter so attractive and pleasing is not always the massage of the letter, it is often the manner and style in which the massage is written.

E.g.: "I wish to express to you my sincere appreciation for your note of congratulation."

or

"I am sincerely happy that you were elected President of Biological Society."

As you see such formulations show the attitude of the writer, his respect and sincerity.

The language of business, professional and semi-official letters is formal, courteous, tactful, concise, expressive, and to the point. A neatly arranged letter will certainly make a better impression on the reader, thus good letters make good business partners.

In the case of "scientific correspondence" the majority of letters bear mostly a semi-official character and are concerned with different situations associated with scientific activities concentrated around the organisation of scientific meetings (congresses, symposia, workshops, etc.), the arrangement of visit, invitation, publication, the exchange of scientific literature, information, etc. Letters of this kind have a tone of friendliness, naturalism. Modern English letters should not be exaggerated, overburdened, outmoded with time-worn expressions. The key note is simplicity. Modern letters tend towards using the language of conversational style.

Writing is not only a means of communication and contract, but also a record of affairs, information, events, etc. So it is necessary to feel the spirit and trend of the style in order to write a perfect letter.

Business-letter or contract law is a complex and vastly documented subject, only a lawyer can deal with it on a serious level. A number of basic principles, however, can be outlined sufficiently to mark of encounters that require the use of specialised English.

Doing business means working out agreements with other people, sometimes through elaborate contracts and sometimes through nothing but little standard forms, through exchanges of letters and conversations at lunch.

Nowadays more and more agreements are made in English, for English is the nearest thing we have to a universal business language. Joint ventures, bank loans, and trademark licenses frequently are spelled out in this language even though it is not native to at least one of the contracting parties.

As a beginning I am going to look at the subject of writing of business letters generally. In the main there are three stages transactions involving business contracts: first, negotiation of terms, second, drafting documents reflecting these terms, and third, litigation to enforce or to avoid executing of these terms. To my mind, a fourth might be added, the administration of contracts.

I am going to look through the first two since the third and the fourth are related only to the field of law. A typical first stage of contract is two or more people having drink and talking about future dealing. A second phase might be letters written in order to work out an agreement.

In these two early stages it will be helpful to know something about rules of contract. But what rules? Different nations borrow or create different legal systems, and even within a single country the rules may vary according to region or the kind of transaction involved.

It is worth knowing that the distinctions in legal system of England are mainly historical.

The history of writing business letters is undoubtedly connected with the history of development of legal language. English is in fact a latecomer as a legal language. Even after the Norman Conquest court pleadings in England were in French, and before that lawyers used Latin. Perhaps, some of our difficulties arise due to the fact that English was unacceptable in its childhood.

Contract in English suggest Anglo-American contract rules. The main point is always to be aware that there are differences: the way they may be resolved usually is a problem for lawyers. With contracts the applicable law may be the law of the place where the contract is made; in other cases it may be the law of the place where the contract is to be performed. It is specified in preliminary negotiations which system of law is to apply.

Diversity is characteristic feature of English; here is a wide range of alternatives to choose from in saying things, although the conciseness is sometimes lacking. Consequently, the use of English is a creative challenge. Almost too many riches are available for selection, that leads occasionally to masterpieces but more frequently to mistakes. English is less refined in its distinctions than French, for example, and this makes it harder to be clear.

That does not mean that English is imprecise for all things are relative. If we compare English with Japanese, we will see that the latter possesses enormous degree of politeness to reflect the respectiveness of speaker and listener as well as of addresser and addressee.

Here I cannot help mentioning the fact that as contracts are so unclear in what every side intends to do, a contract can sometimes put a company out of business.

Thus everybody who is involved in any kind of business should study thoroughly the complex science of writing business letters and contracts.

Business letters throught lexics

From the lexicological point of view isolated words and phrases mean very little. In context they mean a great deal, and in the special context of contractual undertakings they mean everything. Contract English is a prose organised according to plan.

And it includes, without limitation, the right but not the obligation to select words from a wide variety of verbal implements and write clearly, accurately, and/or with style.

Two phases of writing contracts exist: in the first, we react to proposed contracts drafted by somebody else, and in the second, which presents greater challenge, we compose our own.

A good contract reads like a classic story. It narrates, in orderly sequence, that one part should do this and another should do that, and perhaps if certain events occur, the outcome will be changed. All of the rate cards charts, and other reference material ought to be ticked off one after another according to the sense of it. Tables and figures, code words and mystical references are almost insulting unless organised and defined. Without organisation they baffle, without definition they entrap.

In strong stance one can send back the offending document and request a substitute document in comprehensible English. Otherwise a series of questions may be put by letter, and the replies often will have contractual force if the document is later contested.

A sampling of contract phrases

My observations about English so far have been general in nature. Now it appears logical to examine the examples of favourite contract phrases, which will help ease the way to fuller examination of entire negotiations and contracts. a full glossary is beyond reach but in what follows there is a listing of words and phrases that turn up in great many documents, with comments on each one. The words and phrases are presented in plausible contract sequence, not alphabetically.

"Whereas" Everyman's idea of how a contract begins. Some lawyers dislike "Whereas" and use recitation clauses so marked to distinguish them from the text in the contract. There the real issue lies; one must be careful about mixing up recitals of history with what is actually being agreed on. For example, it would be folly to write: "Whereas A admits owing B $10,000..." because the admission may later haunt one, especially if drafts are never signed and the debt be disputed. Rather less damaging would be:

"Whereas the parties have engaged in a series of transactions resulting in dispute over accounting between them..."

On the whole "Whereas" is acceptable, but what follows it needs particular care.

"It is understood and agreed" On the one hand, it usually adds nothing, because every clause in the contract is "understood and agreed" or it would not be written into it. On the other hand, what it adds is an implication that other clauses are not backed up by this phrase: by including the one you exclude the other. «It is understood and agreed» ought to be banished.

"Hereinafter" A decent enough little word doing the job of six ("Referred to later in this document"). "Hereinafter" frequently sets up abbreviated names for the contract parties.

For example:

"Knightsbridge International Drapes and Fishmonger, Ltd (hereinafter "Knightsbridge").

"Including Without Limitation" It is useful and at times essential phrase. Earlier I've noted that mentioning certain things may exclude others by implication. Thus,

"You may assign your exclusive British and Commonwealth rights"

suggests that you may not assign other rights assuming you have any. Such pitfalls may be avoided by phrasing such as:

"You may assign any and all your rights including without limitation your exclusive British and Commonwealth rights".

But why specify any rights if all of them are included? Psychology is the main reason; people want specific things underscored in the contracts, and "Including Without Limitation" indulges this prediction.

"Assignees and Licensees" These are important words which acceptability depends on one's point of view

"Knightsbridge, its assignees and licensees..."

suggests that Knightsbridge may hand you over to somebody else after contracts are signed. If you yourself happen to be Knightsbridge, you will want that particular right and should use the phrase.

"Without Prejudice" It is a classic. The British use this phrase all by itself, leaving the reader intrigued. "Without Prejudice" to what exactly? Americans spell it out more elaborately, but if you stick to American way, remember "Including Without Limitation", or you may accidentally exclude something by implication. Legal rights, for example, are not the same thing as remedies the law offers to enforce them. Thus the American might write:

"Without prejudice to any of my existing or future rights or remedies..."

And this leads to another phrase.

"And/or" It is an essential barbarism. In the preceding example I've used the disjunctive "rights or remedies". This is not always good enough, and one may run into trouble with

"Knightsbridge or Tefal or either of them shall..."

What about both together? "Knightsbridge and Tefal", perhaps, followed by "or either". Occasionally the alternatives become overwhelming, thus and/or is convenient and generally accepted, although more detail is better.

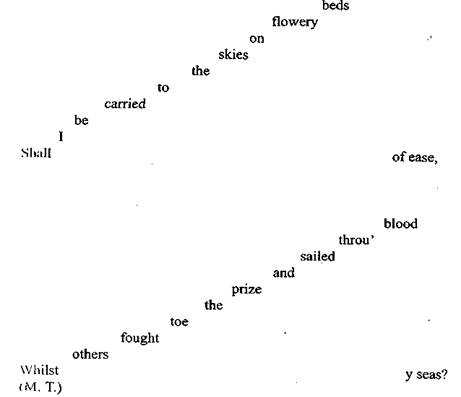

"Shall" If one says "Knightsbridge and/or Tefal shall have..." or "will have...", legally it should make no difference in the case you are consent in using one or the other. "Shall", however, is stronger than "will". Going from one to another might suggest that one obligation is stronger somehow than another. Perhaps, one's position may determine the choice. "You shall", however is bad form.

"Understanding" It is a dangerous word. If you mean agreement you ought to say so. If you view of affairs that there is no agreement, "understanding" as a noun suggests the opposite or comes close to it. .it stands, in fact, as a monument to unsatisfactory compromise. The softness of the word conjures up pleasing images. "In accordance with our understanding..." can be interpreted in a number of ways.

"Effect" Here is a little word which uses are insufficiently praised. Such a phrase as "We will produce..." is inaccurate, because the work will be subcontracted and the promise-maker technically defaults. Somebody else does the producing. Why not say "We will produce or cause to be produced..."? This is in fact often said, but it jars the ear. Accordingly "We will effect production..." highlights the point with greater skill.

"Idea" This word is bad for your own side but helpful against others. Ideas as such are not generally protected by law. If you submit something to a company with any hope of reward you must find better phrasing than "my idea". Perhaps, "my format" or possibly "my property" is more appropriate. Naturally, if you can develop an idea into a format or protectable property, the more ambitious phrasing will be better justified.

"As between us" It is useful, because people are always forgetting or neglecting to mention that a great many interests may be involved in what appears to be simple dialogue. "I reserve control over..." and "You have the final power of decision over..." sound like division of something into spheres, but frequently "I" am in turn controlled by my investors and "You" - by a foreign parent company, making the language of division inaccurate. Neither of us really controls anything, at least ultimately.

Thus it will be useful to say, "As between us, I control..." and so on.

"Spanning" Time periods are awkward things: "...for a period commencing August,1 and expiring November,15..." is clumsy; "...from August,1 to November,15..." is skeletal when informing how long a contract obligation endures.

But during particular time periods one may be reporting for work, for example, three days out of every five, or doing something else that is within but not completely parallel to the entire time period involved.

A happy solution is the word "Spanning". It goes this way:

"Throughout the period spanning August,1 - November,15 inclusive you will render services as a consultant three days out of every five."

It will be useful to put "inclusive" at the end for without it you may lose the date, concluding the period being spanned.

"Negotiate in Good Faith" The negotiators have worked until late at night, all points but one have been worked out, the contract will never be signed without resolution of some particular impasse. What is there to do?

Agree to "Negotiate in Good Faith" on the disputed point at later time. This is done frequently, but make no mistake about the outcome. The open point remains open. If it happens to be vital you may have no contract at all. "Negotiate in Good Faith" is one of those evasions that must be used sparingly. At the right time it prevents collapse, at the wrong time it promotes it.

"Confirm" It suggests, of course, that something has been agreed upon before. You are writing now only to make a record of it. "I write to confirm that you admit substantial default in delivery" Frequently we encounter it in ordinary correspondence: "Confirming your order", "Confirming the main points of our agreement", and so on.

"Furnish" It is a handy word which usefulness lies in the avoidance of worse alternatives. Suppose you transact to deliver a variety of elements as a package.

"Deliver" leaves out, even though it may well be implied, the preliminary purchase or engagement of these elements, and at the other end it goes very far in suggesting responsibility for getting the package unscathed to where it belongs.

Alternatives also may go wrong, slightly, each with its own implications.

"Assign" involves legal title; "give" is lame and probably untrue; "transmit" means send.

Thus each word misses some important - detail or implies unnecessary things.

"Furnish" is sometimes useful when more popular words fall short or go too far. It has a good professional ring to it as well:

"I agree to furnish all of the elements listed on Exhibit A annexed hereto and made part hereof by incorporation."

Who is responsible for non-delivery and related questions can be dealt with in separate clauses.

"Furnish" avoids jumping the gun. It keeps away from what ought to be treated independently but fills up enough space to stand firm.

The word is good value.

"Right but Not Obligation" One of the most splendid phrases available. Sometimes the grant of particular rights carries with it by implication a duty to exploit them. Authors, for example, often feel betrayed by their publishes, who have various rights "but do nothing about them." Royalties decrease as a result; and this situation, whether or not it reflects real criminality, is repeated in variety of industries and court cases. Accordingly it well suits the grantee of rights to make clear at the very beginning that he may abandon them. This possibility is more appropriately dealt with in separate clauses reciting the consequences. Still, contracts have been known to contain inconsistent provisions, and preliminary correspondence may not even reach the subject of rights. A quick phrase helps keep you out of trouble: "The Right but Not Obligation". Thus,

"We shall have the Right but Not Obligation to grant sublicenses in Austria"("But if we fail, we fail").

Even this magic phrase has its limitations because good faith may require having a real go to exploiting the rights in question. Nevertheless "Right but Not Obligation" is useful, so much so as to become incantation and be said whenever circumstances allow it. I the other side challenges these words, it will be better to know this at once and work out alternatives or finish up the negotiations completely.

"Exclusive" It’s importance in contract English is vast, and its omission creates difficulties in good many informal drafts. Exclusivity as a contract term means that somebody is -barred from dealing with others in a specified area. Typically an employment may be exclusive in that the employee may not work for any one else, or a license may be exclusive in the sense that no competing licenses will be issued.

Antitrust problems cluster around exclusive arrangements but they are not all automatically outlawed.

It follows that one ought to specify whether or not exclusivity is part of many transactions. If not, the phrase "nonexclusive" does well enough. On the other hand, if a consultant is to be engaged solely by one company, or a distributorship awarded to nobody else except X, then "exclusive" is a word that deserves recitation. "Exclusive Right but Not Obligation" is an example that combines two phrases discussed here.

The linking of concepts is a step in building a vocabulary of contract English.

"Solely on condition that" One of the few phrases that can be considered better than its short counterparts. Why not just "if"? Because "if" by itself leaves open the possibility of open contingencies:

"If Baker delivers 1,000 barrels I will buy them" is unclear if you will buy them only from Baker. Therefore what about "only if"? Sometimes this works out, but not always.

"I will buy 1,000 barrels only if Baker delivers them" is an example of "only if" going fuzzy. One possible meaning is "not more than 1,000 barrels" with "only" assimilated with the wrong word. Here then a more elaborate phrase is justified.

"I will buy 1,000 barrels solely on condition that Baker delivers them" makes everything clear.

"Subject to" Few contracts can do without this phrase. Many promises can be made good only if certain things occur. The right procedure is to spell out these plausible impediments to the degree that you can reasonably foresee them.

"We will deliver these subject to our receiving adequate supplies";

"Our agreement is subject to the laws of Connecticut";

"Subject to circumstances beyond our control ".

Foreign esoteric words

Every now and then a scholarly phrase becomes accepted in business usage. "Pro rate" and "pari passu" are Latin expressions but concern money. "Pro rata" proves helpful when payments are to be in a proportion reflecting earlier formulas in a contract. "Pari passu" is used when several people are paid at the same level or time out of a common fund. Latin, however, is not the only source of foreign phrases in business letters.

"Force majeure" is a French phrase meaning circumstances beyond one's control.

English itself has plenty of rare words. One example is "eschew"; how many times we see people struggling with negatives such as "and we agree not to produce (whatever it is) for a period of X". The more appropriate phrase would be

"we will eschew production".

But here it should be mentioned that not everyone can understand such phrases. Therefore rare words should be used only once in a long while. Those who uses them sparingly appears to be reliable.

Some words against passive

Until now the study of writing business letters has consisted largely of contract phrases accompanied by brief essays evaluating their usefulness. The words are only samplings and are presented mainly to conduce writing business letters in a proper way. It will be wrong, however, to bring this list to an end without mention of a more general problem that arises in connection with no fixed word pattern at all. It arises, rather from using too many passives. Such phrases as "The material will be delivered";

"The start date is to be decided";

"The figures must be approved" are obscure ones leaving unsettled who it is that delivers, who decides, and who does the approving. Which side it is to be? Lawsuits are the plausible outcome of leaving it all unsettled. Passives used in contracts can destroy the whole negotiations. "You will deliver" is better for it identifies the one who will do delivering. Certainly, "must be approved by us" violates other canons. "We shall have the right but not the obligation to approve" is less unfortunate. There is no doubt that passives do not suit business letters, and if they go all the way through without adding something like "by you" or "by us" they are intolerable. Once in a long while one may find passives used purposely to leave something unresolved. In those circumstances they will be in class with "negotiate in good faith", which I've examined earlier.

Examining english business letters

Now let's turn to the practical point of writing business letters. They may be divided into official and semi-official. The first kind of letters is characteristic of those people working in business: an executive, a department manager, a salesman, a secretary or a specialist in business and technology. But also many people may want to buy something, to accept an invitation or to congratulate somebody - this is a kind of semi-official letters. The first kind of letters may in turn be subdivided into such groups as: inquiries, offers, orders, and so on. I am going to examine this group more carefully looking at the correspondence of Chicago businessmen and English manufactures.

.

Example 1.

MATTHEWS & WILSON

Ladies' Clothing

Похожие работы

... the rules may vary according to region or the kind of transaction involved. It is worth knowing that the distinctions in legal system of England are mainly historical. The history of writing business letters is undoubtedly connected with the history of development of legal language. English is in fact a latecomer as a legal language. Even after the Norman Conquest court pleadings in England ...

... , Conclusion and Appendix. Kazakh State University of International Relations and World Languages named after Abylay Khan Chair of LexicologyE. Gadyukova Group 406 English Teaching DepartmentThe Linguistic Background of Business Correspondence(Diploma Paper)Scientific Supervisor Associated Professor Bulatova S. M.Almaty, 2001 Part I The Basic Forms Of Communication As David Glass is well aware, ...

of promoting a morpheme is its repetition. Both root and affixational morphemes can be emphasized through repetition. Especially vividly it is observed in the repetition of affixational morphemes which normally carry the main weight of the structural and not of the denotational significance. When repeated, they come into the focus of attention and stress either their logical meaning (e.g. that of ...

... compound-shortened word formed from a word combination where one of the components was shortened, e.g. «busnapper» was formed from « bus kidnapper», «minijet» from «miniature jet». In the English language of the second half of the twentieth century there developed so called block compounds, that is compound words which have a uniting stress but a split spelling, such as «chat show», «pinguin ...

0 комментариев