Навигация

The post-climax of the comedy

6.1.2 The post-climax of the comedy

All loose ends of the plot have already been tied; what happens in the scene we already know, save for the selection of the workmen’s play, which is not surprising. The play is a celebration of marriage:

· the “tragical mirth” of Pyramus and Thisbe in its original story points to the dangers of passionate love, from which our lovers have been delivered;

· in its dialogue and performance, it shows that creating dramatic narrative is not for amateurs;

· but in its well-meaning presentation to the newly-weds it proves Theseus right in his claim that “…never any thing can be amiss/When simpleness and duty tender it”.

The presence of the mechanicals at the wedding feast reflects the connected or organic nature of hierarchical society, and identifies the good ruler with his loyal subjects. A far more serious celebration follows: the fairies, led by their king and queen and the inevitable Puck, bring to the bedchambers the fertility, and to the children, in due course, the good health which all those in the audience would wish to enjoy. This is remarkably simple, but is formally arranged:

· the discussion of the lovers’ “dreams” at the start of the scene mirrors Puck’s description of the audience’s slumbering “while these visions did appear”;

· the hilarious and good-natured entertainment at the wedding-feast gives way to a more serious, but equally joyful, blessing by the fairies;

· reversing the order in 4.1, Theseus’ exit is followed moments later by the entrance of the fairy king: day gives way to Night’s, earthly rule to that of the good spirits, as Theseus understands in urging retirement to bed, not because he is impatient, or overwhelmed with desire, but because: “’T is almost fairy time”.[7]

The opening of the scene is quite intimate: Theseus speaks seriously to Hippolyta (he is not inhibited by the presence of so trusted a servant as Philostrate; a ruler of his standing would rarely be alone with another person). The episode is fairly static to allow the debate to be heard, but the arrival of the four young newly-weds brings Theseus to a consideration of the short-listed entertainments for his wedding-feast. He is given a written list of these, which he reads, evidently for the first-time, half aloud, half to himself. His interest in Pyramus and Thisbe alarms Philostrate, who tries to dissuade him. When this “play” is performed, we see exaggerated histrionic gestures, and such redundant devices as actors playing the wall, moonshine and the lion. These three introduce themselves and explain what they are doing (the wall also explains his exit from the stage). Bottom and Starveling both step out of character to address their audience directly. For other clues to the nature of the action we must look to the remarks of Theseus and his guests. After the bergomask dance, and the departure of the nobles, we see the far more skilful dancing of the fairies, by means of which they enact their magic. At last, the actor playing Puck steps half out of character to address the audience; to do this he will come to the front of the stage, and end by calling for applause. The set-piece discussion of imagination, especially of “the lunatic, the lover, and the poet” is the last in series of commentaries on reason and love which runs through the whole drama. The long speeches, in tetrameter couplets, of Oberon, Titania and Puck, perfectly fit their r”le here of beneficent and magical spirits. Throughout this play, Shakespeare has used enomous variety of verse forms and prose: almost always these perfectly fit their dramatic context, whether for carrying narrative, expressing argument, meditation on an idea, describing what we cannot see or casting a spell. We often laugh at characters, but we never laugh at the dramatist’s control of his medium. Lest we take this for granted, Pyramus and Thisbe serves as a corrective. We see here what happens when rhetorical devices and rhyme are used mechanically and without sensitivity. Quince’s garbling of the punctuation makes the Prologue less intelligibl;e but no less pompous and windy. We find weak rhymes (“Thisbe/secretly”; “sinister/whisper”), excessive use of “O” (167 ff., but we have caught the lovers doing this before, if to a less degree), crude stichomythia (191-200) and tongue-tying alliteration (“Quail, crush, conclude and quell” or “Come blade my breast imbrue”).Shakespeare shows clearly in the rest of the play how to avoid lines which the actor cannot speak, unless the character is knowingly playing with sound effects) and simple inaccuracy, especially where terms have been mixed up (“I see a voice”; “Sweet Moon, I thank thee for thy sunny beams”; “These lily lips,/This cherry nose,/These yellow cowslip cheeks”). The play is not so bad that the workmen cannot plausibly take pride in it. But the educated nobles can see its faults readily. Of course, we can see skill in its composition: Shakespeare has contrived the verse form, so that errors and crudities are pointed by the rhymes, and the whole has a rollicking metrical energy which exactly matches the gusto of the inexpert but enthusiastic actors. The male and female leads have lines which are meant to give scope for the actors’ great talent: there are fairly long speeches, with overwrought climaxes. We suppose that while Bottom is cast as Pyramus because his exaggerated delivery commands respect among the workmen, Flute is cast as Thisbe because he is the youngest man (his beard is only now beginning to grow).

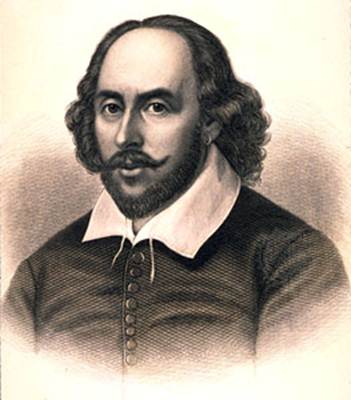

Chapter 2. The brilliant majesty of Shakespearean language one the example of the comedy “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

Похожие работы

... the guises provided by their respective archetypes. The “Daughter”/“Niece” Binary in As You Like It The “daughter” and “niece” archetypes, of course, are not universally applicable to all women in Shakespeare’s comedies. In As You Like It, there are other female characters which defy such classification. Phoebe, for example, exhibits traits of both “niece” (in her willful pursuit of the ...

... property in the town. John Shakespeare married Mary Arden, the daughter of Robert Arden. John and Mary set up home in Henley Street, Stratford, in the house now known as Shakespeare’s Birthplace . John and Mary lost two children before William was born. They had five more children, another of whom died young. As the son of a leading townsman, William almost certainly attended Stratford’s ‘petty’ ...

... marked. Thus Romeo and Juliet differs but little from most of Shakespeare's comedies in its ingredients and treatment-it is simply the direction of the whole that gives it the stamp of tragedy. Romeo and Juliet is a picture of love and its pitiable fate in a world whose atmosphere is too sharp for this, the tenderest blossom of human life. Two beings created for each other feel mutual love at the ...

... texts were available. Subsequently Henry V (1600) was pirated, and Much Ado About Nothing was printed from "foul papers"; As You Like It did not appear in print until it was included in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories & Tragedies, published in folio (the reference is to the size of page) by a syndicate in 1623 (later editions appearing in 1632 and 1663). The only precedent for ...

0 комментариев