Навигация

Divide the class into pairs. Ask the pairs to draw up a list of English-speaking

1. Divide the class into pairs. Ask the pairs to draw up a list of English-speaking

speaking countries, that is to say, countries where English is an official language

or is widely spoken. Be available to help supply the names of countries in English.

2. On the board draw five columns and head them with the names of the main continents. Ask your students for the names of the countries they wrote down in Step 1 and write them in the appropriate column. When you have exhausted their lists, add any others you feel they should know. The main countries are:

Europe: Cyprus, Gibraltar, Ireland, Malta, The United Kingdom

Africa: Botswana, The Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Namibia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe

Asia: Bangladesh, Brunei, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka

Australia and the Pacific: Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, Tonga

The Americas: Canada, The United States, Belize, many of the Caribbean islands, including The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St Lucia, St Vincent, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, the Falkland Islands

3. Explain to the class that you want them to do a project on one of these countries but not on England or the United States. Tell the class to form groups of three or four. Let your students choose their partners, while making sure no individuals get left out. Ask each group to choose a country. Allow more than one group to work on the same country – they often use quite different approaches and present interestingly different work – but you may decide you want your students to do different work on as broad a range of countries as possible, in which case they should all choose different countries.

4. When your students have chosen their countries, ask each group, for your reference, to give you a piece of paper with the names of the members in their group and which country they are going to work on.

5. Establish with the class the following:

a) how much you want each student to contribute to the project;

b) the content - set an upper limit of one third dedicated to the general background (geography and history, currency, industries, etc.) and insist that the greater part should be dedicated to the use of the English language, e.g. the role of English, how it differs from standard British/American English, periodicals published in English, literature, etc. The possible areas of focus here vary considerably from country to country and you may need to discuss with each group those areas that would offer the most potential, e.g. the question of language variety is more appropriate where most or all of the population is English-speaking, the periodicals published in English are more relevant where English is one of the many languages used in the country;

c) the deadline by which the project must be handed in.

6. Discuss with your students what sources of information they are going to use. Students work mostly from five sources:

a) encyclopedia entries;

b) books;

c) newspaper and magazine articles;

d) computer programs;

e) information from embassies, high commissions and tourist offices.

You may be able to provide support from material you yourself possess - this is where it is useful to have a list of groups and their countries, so that you know who to give it to.

CONCLUSIONS

The objectives of the paper were to highlight the importance of the project work in teaching English, to discover how it influences the students during the educational process and if this type of work in the classroom helps to learn the language.

On the basis of the literary sources studied we can come to the following conclusions that project work has advantages like the increased motivation when learners become personally involved in the project; all four skills, reading, writing, listening and speaking, are integrated; autonomous learning is promoted as learners become more responsible for their own learning; there are learning outcomes -learners have an end product; authentic tasks and therefore the language input are more authentic; interpersonal relations are developed through working as a group; content and methodology can be decided between the learners and the teacher and within the group themselves so it is more learner-centred; learners often get help from parents for project work thus involving the parent more in the child's learning; if the project is also displayed parents can see it at open days or when they pick the child up from the school; a break from routine and the chance to do something different.

The disadvantages of project work are the noise which is made during the class, also projects are time-consuming and the students use their mother tongue too much, the weaker students are lost and not able to cope with the task and the assessment of projects is very difficult. However, every type of project can be held without any difficulties and so with every advantage possible.

The types of projects are information and research projects, survey projects, production projects and performance and organizational projects which can be performed differently as in reports, displays, wall newspapers, parties, plays, etc.

Though project work may not be the easiest instructional approach to implement, the potential pay-offs are many. At the very least, with the project approach, teachers can break with routine by spending a week or more doing something besides grammar drills and technical reading.

The organization of project work may seem difficult but if we do it step by step it should be easy. We should define a theme, determine the final outcome, structure the project, identify language skills and strategies, gather information, compile and analyse the information, present the final product and finally evaluate the project. Project work demands a lot of hard work from the teacher and the students, nevertheless, the final outcome is worth the effort.

Throughout the course paper we can see that project work has more positive sides than negative and is effective during the educational process. Students are likely to learn the language with the help of projects and have more fun.

To conclude, project work is effective, interesting, entertaining and should be used at the lesson.

LIST OF REFERENCES

1. Haines S. Projects for the EFL Classroom: Resource materials for teachers. – Walton-on-Thames: Nelson, 1991. – 108p.

2. Phillips D., Burwood S., Dunford H. Projects with Young Learners. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. – 160p.

3. Brumfit C. Communicative Methodology in Language Teaching. The Roles of Fluency and Accuracy. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. – 500p.

4. Fried-Booth D. Project Work. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990. – 89p.

5. Hutchinson T. Introduction to Project Work. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. – 400p.

6. Legutke M., Thomas H. Process and Experience in the Language Classroom. – Harlow: Longman, 1991. – 200p.

7. Phillips D., Burwood S., Dunford H. Projects with Young Learners. Resource Books for Teachers – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. – 153p.

8. Ormrod J. F. Education Psychology: Developing Learners. – Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000. – 627 p.

9. Emmer E. T., Evertson C. M., Worsham M. E. Classroom Management for Successful Teachers (4th edition). – Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1997. – 288 p.

10. Brown H.D. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching (4th edition). – Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000. – 320-355 p.

11. Finegan E. Language: Its Structure and Use (3rd edition). – Oxford: Heinemmann, 1999. – 158 p.

12. Estaire S., Zanon J. Planning Classwork. A task-based approach. – Oxford: Heinemmann, 1994. – 93p.

13. Lavery C. Focus on Britain Today. Cultural Studies for the Language Classroom. – London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd, 1993. – 122p.

14. Ribe R., Vidal N. Project Work. Step by Step. – Oxford: Heinmann, 1993. – 94p.

15. Wicks M. Imaginative Projects. A resource book of project work for young students. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. – 128p.

16. Зимняя И. А., Сахарова Т. Е. Проектная методика обучения английскому языку // Иностранные языки в школе., 1991. – №3 – С.9-15.

17. Полат Е. С. Метод проектов на уроках иностранного языка // Иностранные языки в школе., 2000. – №2 – С.3-10 - №3 – С.3-9.

18. Gray S. Communication through Projects. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994. – 350p.

19. Morris P. The Management of Projects. – London: Thomas Telford Services Ltd., 1994. – 450p.

20. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project Work

Похожие работы

... learners. Chapter 2 describes importance of using pair work and group work at project lessons. Chapter 3 shows how to use project work for developing all language skills. Chapter 4 analyses the results of the questionnaire and implementation of the project work “My Body” in form 4. 1. Aspects of Intellectual Development in Middle Childhood Changes in mental abilities – such as learning, memory, ...

... Intelligences, The American Prospect no.29 (November- December 1996): p. 69-75 68.Hoerr, Thomas R. How our school Applied Multiple Intelligences Theory. Educational Leadership, October, 1992, 67-768. 69.Smagorinsky, Peter. Expressions:Multiple Intelligences in the English Class. - Urbana. IL:National Council of teachers of English,1991. – 240 p. 70.Wahl, Mark. ...

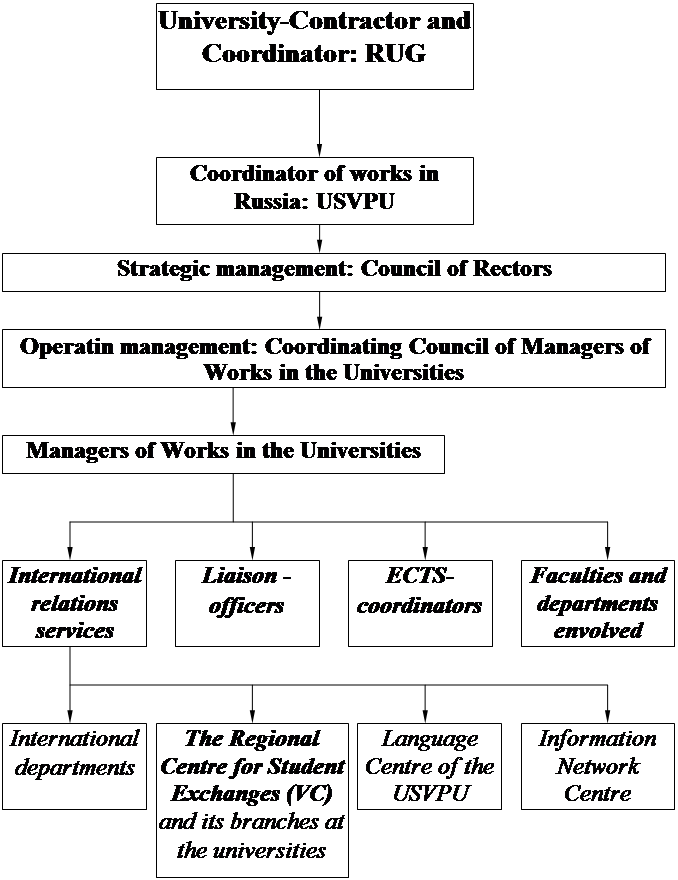

... allow to operate and to realize these programs successfully. Mrs. Lieve Bracke has been acting as the coordinator of student exchange programs between the Santander group universities ICP-94-NL-2020/17, joint European projects on student exchanges with Hungary (in several specialities) and pre-project Pre-JEP 00304-93 with Kiev University (Ukraine), in which university of Leeds (Great Britain) ...

... development and self-development, ability to make a creative decision in the course of a dialogue. Therefore it is necessary to give special attention to development not only intellectual, but also creative abilities of trainees. creative game english independence student Practice has shown that positive transformations of a society cannot be reached within the limits of traditional model of ...

0 комментариев