Навигация

Choose Your Words Carefully

7. Choose Your Words Carefully

Linguists estimate that the English language includes over one million words, thus providing English speakers with the largest lexicon in the world. From this vast lexicon, writers may choose the precise words to meet their needs. The list below describes some of the factors you might consider in choosing, from among a number of synonyms or near synonyms, the word or phrase most appropriate to your purpose. Notice that the distinctions between these factors are not always sharp; some might properly be considered subsets of others. For example, tone, formality, and intensity might be considered subsets of connotation.

a. Connotation: While the literal or explicit meaning of a word or phrase is its denotation, the suggestive or associative implication of a word or phrase is its connotation. Words often have similar denotations but quite different connotations (due to etymology, common usage, suggestion created by similar-sounding words, etc.); hence, you might choose or avoid a word because of its connotation. For example, although one denotation of rugged is "strongly built or constituted," the connotation is generally masculine; hence, you might choose to describe an athletic woman as athletic rather than rugged. Likewise, although one denotation of pretty is "having conventionally accepted elements of beauty," the connotation is generally feminine; thus, most men would probably prefer being referred to as handsome.

b. Tone: While the denotation of a word expresses something about the person or thing you are discussing, the tone of a word expresses something about your attitude toward the person or thing you are discussing. For example, the following two sentences have similar denotations, but very different tones:

The senator showed himself to be incompetent.

The senator showed himself to be a fool.

c. Level of Formality: Some dictionaries indicate whether a word is formal, informal, vulgar, or obscene; most often, however, your own sensitivity to the language should be sufficient to guide you in making the appropriate choice for a given context. In writing a report about the symptoms of radiation sickness, for example, you would probably want to talk about "nausea and vomiting" rather than "nausea and puking."

Be aware, however, that achieving an appropriate level of formality is as much a question of choosing less formal as it is of choosing more formal words. As Strunk and White point out, "Avoid the elaborate, the pretentious, the coy, and the cute. Do not be tempted by a twenty-dollar word when there is a ten-center handy, ready, and able." And Joseph Williams adds, "When we pick the ordinary word over the one that sounds more impressive, we rarely lose anything important, and we gain the simplicity and directness that most effective writing demands" (Style, 1st ed.).

You might, for example, replace initiate with begin, cognizant with aware, and enumerate with count. Williams offers the following example and translation of inflated prose:

Pursuant to the recent memorandum issued August 9, 1979, because of petroleum exigencies, it is incumbent upon us all to endeavor to make maximal utilization of telephonic communication in lieu of personal visitation.

As the memo of August 9 said, because of the gas shortage, try to use the telephone as much as you can instead of making personal visits.

Remember, as Abraham Lincoln said, "You can fool all of the people some of the time, and you can even fool some of the people all of the time, but you can't fool all of the people all of the time." The more sophisticated your audience, the more likely they are to be put off, rather than impressed, by inflated prose.

d. Intensity: Intensity is the degree of emotional content of a word—from objective to subjective, mild to strong, euphemistic to inflammatory. It is common, for example, for wildlife managers to talk about harvesting deer rather than killing them. Choosing a less intense word or phrase can avoid unnecessarily offending or inciting your readers; however, it can also be a means of avoiding responsibility or masking the unsavory nature of the situation. As George Orwell says in "Politics and the English Language": "In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. . .. Thus, political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question begging, and sheer cloudy vagueness."

Achieving the appropriate level of intensity is as often a question of choosing the more intense as it is of choosing the less intense word. Ultimately, you must rely upon your own sensitivity to the language, to your topic, and to your audience to guide you in making the appropriate choices for a given context.

e. Level of Abstraction: According to Strunk and White,

If those who have studied the art of writing are in accord on anyone point, it is on this: the surest way to arouse and hold the attention of the reader is by being specific, definite, and concrete. The greatest writers. . .are effective largely because they deal in particulars and report the details that matter. Their words call up pictures.

For example, if we move down in the hierarchy of abstraction from thing to plant to tree to birch to gray birch, we can see that each step offers the reader a clearer picture of what's being discussed.

The general and the abstract do have their place. There are times, for example, when we want to talk about "humankind" or "life on Earth," but it's often wise to support the general with the specific, the abstract with the concrete: "Carl Sagan's research suggests that a nuclear winter would destroy all life on Earth—every tree, every flower, every child."

f. Sound: All other things being equal, you may want to choose one word rather than another simply because you like its sound. Although what you're writing may never be read aloud, most readers do "hear" what they read via an inner voice. Hence, the "sound" of your writing can add to or detract from its flow and, thus, influence the reader's impression of what you've written.

g. Rhythm: Although rhythm is quantifiable, most writers rely on their ear for language to judge this aspect of their sentences. Like sound, rhythm in prose is often an "all-other-things-being-equal" consideration. That is, you wouldn't want to choose the wrong word simply to improve the rhythm of your sentence. However, rhythm can contribute to the flow of your writing, and a sudden break in rhythm can create emphasis. Hence, you may choose one synonym over another simply because it has more or fewer syllables and, thus, contributes to the rhythm of your sentence. Even an occasional bit of deadwood may be justified if it contributes to the rhythm of your sentence.

Finally, note that rhythm is especially important in parallel structures and is often a factor in sentence-to-sentence flow; that is, you must read a sequence of sentences in context to judge their rhythm.

h. Repetition: Using the same word to refer to the same thing or idea is desirable when it contributes to transition and coherence. For example, substituting commands for translators in the second pair of sentences below provides a smoother transition:

This section describes the commands used for translating programs written in the four languages mentioned above. These translators create object-code files with a filetype of TEXT from programs written by the user.

This section describes the commands used for translating programs written in the four languages mentioned above. These commands create object-code files with a filetype of TEXT from programs written by the user.

Sometimes, however, repeating the same word can become awkward, tedious, or confusing. Alternating between a pronoun and its antecedent is one obvious way of avoiding the tedious repetition of the same word to refer to the same thing. You can usually help to avoid confusing your readers by not using the same word (or variations of the same word) to mean two different things in one sentence or in two closely related sentences:

no: Output from VM is displayed in the output display area.

yes: Output from VM appears in the output display area.

Похожие работы

... as in his defective stories, or terror, as is the case of “The Cask Of Amontillado”. Poe’s tales of terror are perhaps, more widely known to the general reader than his defective stories. Poe’s short narrative prose style as found in the two categories characteristic of his fiction has widely influenced the form and purpose of the short story, not only in the United States, but also around the ...

of promoting a morpheme is its repetition. Both root and affixational morphemes can be emphasized through repetition. Especially vividly it is observed in the repetition of affixational morphemes which normally carry the main weight of the structural and not of the denotational significance. When repeated, they come into the focus of attention and stress either their logical meaning (e.g. that of ...

... materials based on electric devices manuals are studied. In the next chapter lexical and grammatical peculiarities have been reviewed. 2. Lexical and grammatical peculiarities of scientific-technical texts In any scientific and technical text, irrespective of its contents and character, can be completely precisely translated from one language to other, even if in an artwork such branch of ...

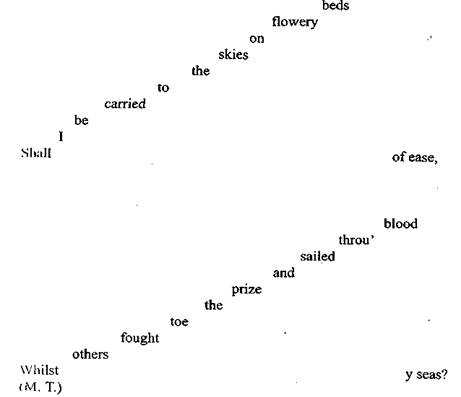

ams, elegies, songs, satires and sermons. His poetry is noted for its vibrancy of language and inventiveness of metaphor, especially as compared to that of his contemporaries. John Donne's masculine, ingenious style is characterized by abrupt openings, paradoxes, dislocations, argumentative structure, and "conceits"--images which yoke things seemingly unlike. These features in combination with ...

0 комментариев