Навигация

Use Metaphor to Illustrate

12. Use Metaphor to Illustrate

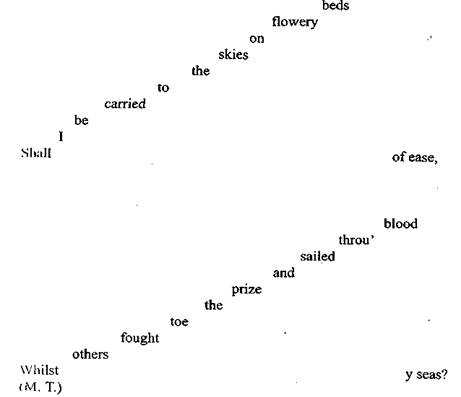

Metaphor may be broadly defined as an imaginative comparison, expressed or implied, between two generally unlike things, for the purpose of illustration. By this definition, similes (expressed comparisons) are a subset of metaphor. In prose (as opposed to poetry), metaphors are most often used to illustrate, and thus make clear, abstract ideas: "When two atoms approach each other at great speeds they go through one another, while at moderate speeds they bound off each other like two billiard balls" (Sir William Bragg).

Whenever you use figurative language, be careful to avoid cliches—trite, overworn words or phrases that have lost their power to enliven your writing. If you can't think of a fresh, imaginative way to express an idea, it's better to express it in literal terms than to resort to a cliche. Hence,

Solving the problem was as easy as pie.

becomes

Solving the problem was easy.

Note that even solitary nouns, verbs, and modifiers can be cliched. For example,

He's such a clown.

I've got to fly.

The competition was stiff.

Often such cliches are what George Orwell calls "dying metaphors"—words and phrases that were once used figuratively, but that now border on the literal. That is, we've used these terms so often that we now scarcely consider their figurative implications.

As with tone, rhythm, and many of the other stylistic considerations discussed here, you must ultimately rely upon your own sensitivity to the language to guide you in determining when a word or phrase is cliched.

Finally, according to Collett Dilworth and Robert Reising, the golden rule of writing is "to write to be read fluently by another human being . . . the most moral reason for observing any specific writing convention is that it will shape and facilitate a reader's understanding, not simply that it will be used 'correctly'." So as George Orwell says in "Politics and the English Language": "Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous."

BASIC PUNCTUATION AND MECHANICS

1. Commas

1.1 (a) Use a comma before a coordinating conjunction (and, but, or, for, nor, yet, so) that joins two independent clauses (compare 2.1). (An independent or main clause is a clause that can stand by itself as a separate sentence.):

The children escaped the fire without harm, but their mother was not so lucky.

(b) If the clauses are short and closely related, a comma is not required:

Frank typed and Matt watched.

(c) If the coordinate clauses are long or themselves contain commas, you can often avoid confusion by separating them with semicolons:

Paul went to his car, got a gun, and returned to the lake; but Bill, unfortunately, refused to be intimidated.

1.2 Use a comma to separate an introductory element (clause, phrase, conjunctive adverb, or mild interjection) from the rest of the sentence:

If you refuse to leave, I'll call the police. (clause)

To prepare for her exam, Lynn reread all of her notes. (phrase)

Nevertheless, much work still remains to be done. (conjunctive adverb)

Well, I was surprised to achieve these results. (interjection)

1.3 (a) Use commas to set off parenthetical elements or interrupters (including transitional adverbs):

The report, which was well documented, was discussed with considerable emotion. (nonrestrictive clause)

They were, however, still able to meet their deadline.(transitional adverb)

An important distinction must be made here between restrictive and nonrestrictive modifiers. Restrictive modifiers are essential to the meaning of the sentence in that they restrict that meaning to a particular case. Hence, restrictive modifiers are not parenthetical and cannot be removed without seriously damaging the meaning. Since they are necessary to the meaning, restrictive modifiers are not set off by commas:

All soldiers who are overweight will be forced to resign.

Nonrestrictive modifiers are parenthetical. That is, they digress, amplify, or explain, but are not essential to the meaning of the sentence. These modifiers simply provide additional information for the reader—information which, although it may be interesting, does not restrict the meaning of the sentence and can be removed without changing the sentence's essential meaning:

Sgt. Price, who is overweight, will be forced to resign.

(b) Use commas to set off parenthetical elements that retain a close logical relationship to the rest of the sentence. Use dashes or parentheses to set off parenthetical elements whose logical relationship to the rest of the sentence is more remote (compare 4.2 and 5.1).

1.4 Use commas to join items in a series. Except in journalism, this includes a comma before the conjunction that links the last item to the rest of the series:

Before making a decision, he studied the proposition, interviewed many of the people concerned, and tried to determine if there were any historical precedents.

1.5 Although not called for by any of the above principles, commas are sometimes required to avoid the confusion of mistaken junction:

She recognized the man who entered the room, and gasped.

2. Semicolons

2.1 Use a semicolon to join two independent clauses that are closely related in meaning and are not joined by a coordinating conjunction (compare 1.1):

A filemode digit of 3 identifies a temporary file; temporary files are deleted automatically after being read.

2.2 Use a semicolon to join two independent clauses when the second one begins with or includes a conjunctive adverb (nevertheless, therefore, however, otherwise, as a result, etc.) (compare 1.3):

If CMS is waiting, the entry will be processed immediately; otherwise, it will be queued until requested.

2.3 To avoid confusion, use semicolons to separate items in a series when one or more of the items includes commas (see also 1.1c):

This manual also summarizes the Graduate School's mechanical requirements for theses; discusses the special requirements of students who are submitting computer programs as theses; reviews basic principles of punctuation, mechanics, and style; and refers student s to standard references on punctuation, mechanics, style, and usage.

3. Colons

3.1 Use a colon to introduce a list, an example, an amplification, or an explanation directly related to something just mentioned (compare 4.1) and 4.4):

The user may work from one of three modes when typing data into the file area: edit mode, input mode, or power typing. He eventually found that there was only one way to get the quality he expected from the people who worked for him: treat them with respect.

3.2 Use a colon to introduce a formal statement or quotation (usually of more than one line):

Writers who care about the quality of their work would do well to heed Samuel Johnson's advice: What is written without effort is in general read without pleasure.

4. Dashes

If your word-processor doesn't have an em-dash (a dash that is the width of a capital M) in its special character set, use two hyphens (--) to make a dash. Whichever one you use, except in journalism, you should leave no space between or on either side of the dash itself. Dashes are more widely accepted today than they were in the past; however, many writers and editors still consider them to be somewhat less formal marks of punctuation—use them sparingly.

4.1 Use a dash to introduce a summarizing word, phrase, or clause, such as an appositive (a noun set beside another noun and identifying or explaining it) (compare 3.1):

The strikers included plumbers, electricians, carpenters, truck drivers—all kinds of workers.

4.2 Use dashes to mark off a parenthetical element that represents an abrupt break in thought. Dashes give more emphasis to the enclosed element than do either commas or parentheses (compare 5.1):

Reagan's sweep of the South—he won every state but Georgia—was the most humiliating defeat for Carter.

4.3 To avoid confusion, use dashes to mark off parenthetical elements that contain internal commas:

Seven of our first twelve presidents—Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Harrison, Tyler, and Taylor—were from Virginia.

4.4 Dashes can be used as a less formal alternative to the colon to introduce an example, explanation, or amplification (see 3.1).

For more on the use of dashes in journalism, see the entry on dashes in the Guide to Punctuation in the Associated Press Stylebook.

5. Parentheses

5.1 (a) Use parentheses to enclose parenthetical elements (words, phrases, or complete sentences that digress, amplify, or explain) (compare 1.3b) and 4.2).

When APL is on (indicated by the letters APL appearing at the bottom of the screen), no lower-case characters are available.

(b) A parenthesized sentence that appears within another sentence need not begin with a capital or end with a period.

(c) A comma may follow the closing parenthesis (if needed), but one should not precede the opening parenthesis.

5.2 Except in journalism, use square brackets [ ] to enclose a parenthetical element within a parenthetical element.

6. Ellipsis Dots

6.1 Use three dots

(a) to signal the omission of a word or words from the middle of a quoted sentence:

A senior White House official again asserted the administration's position: "We will not negotiate any treaty with the Soviets . . .unless it is verifiable."

(b) to signal hesitation or halting speech in dialogue:

"I . . . don't know what to say," he whispered.

6.2 Use four dots

(a) to signal the omission of the end of a quoted sentence:

"Of all our maladies, the most barbarous is to despise our being. . . . For my part, I love life and cultivate it."

— Montaigne

(b) to signal the omission of one or more whole sentences.

Except in journalism, ellipses dots should be spaced ( . . . vs. …).

7. Hyphens

7.1 To express the idea of a unit and to avoid ambiguity, hyphenate compound nouns and compound modifiers that precede a noun:

She was a scholar-athlete.

All-night terminal sessions are counterproductive.

The IBM 4250 printer has all-points-addressable graphics capabilities.

7.2 Use a hyphen between the components of any number (including fractions) below one hundred that is written as two words: thirty-five two-thirds

8. Apostrophes

8.1 Use apostrophe, s ('s) to indicate singular possessive:

Users keep turning on to IBM's VM operating system.

8.2 Use s, apostrophe (s') to indicate plural possessive:

We found the missing tools in the boys' clubhouse.

8.3 Use apostrophe, s ('s) to form the plural of abbreviations with periods, lowercase letters used as nouns, and capital letters that would be confusing if s alone were added:

M.A.'s and Ph.D.'s x's and y's S's, A's, I's SOS's

8.4 When you can do it without creating confusion, use s alone to form the plural of letters, figures, words treated as words, and hyphenated coinages used as nouns:

three Rs four 8sthey came in twos the 1980s a dozen ifs

9. Italics

9.1 Use italics (sparingly) to emphasize a word or phrase:

The GET command inserts data from the current line forward, so the user must be sure to make the appropriate line the current line before entering this command.

9.2 Use italics to identify a letter treated as a letter or a word treated as a word:

The word eyes appears twice in the first line of the poem.

9.3 Use italics to identify foreign words or phrases not yet absorbed into English.

10. Titles

10.1 Italicize (or underline) the titles of books, magazines, journals, newspapers, plays, operas, films, television shows, radio programs, and long poems.

10.2 Enclose in quotation marks the titles of short poems, essays, magazine articles, newspaper columns, short stories, songs, speeches, and chapters of books.

In journalism, see the following entries in the Associated Press Stylebook: "composition titles," "magazine names," "newspaper names." In summary, these entries indicate that most composition titles (books, plays, songs, television shows, etc.) should be enclosed in quotation marks but not in italics. Newspaper and magazine titles, however, should neither be italicized nor enclosed in quotation marks.

11. Numbers

11.1 Spell out a number when it begins a sentence.

11.2 Spell out a number that can be written in one or two words (except as noted in 11.3) and 11.5):

three twenty-two five thousand one million

11.3 If numbers that can be written as one or two words cluster closely together in the sentence, use numerals instead:

The ages of the members of the city council are 69, 64, 58, 54,47, 45, and 35.

11.4 Use numerals if spelling out a number would require more than two words:

3507,1254,978,2655.78

11.5 Use numerals for addresses, dates, exact times of day, exact sums of money, exact measurements (including miles per hour), game scores, mathematical ratios, and page numbers:

55 mph ratio of 4-to-1 $6.75 p. 37

In journalism, see the numerals entry in the Associated Press Stylebook.

12. Quotation Marks

12.1 Use double quotation marks to create irony by setting off words you don't take at face value:

The "debate" resulted in three cracked heads and two broken noses.

12.2 Do not use quotation marks to create emphasis (see 9.1).

12.3 Use single quotation marks to enclose a quotation within a quotation:

At the beginning of the class, the professor asked, "What does Kuhn mean by 'paradigm shifts,' and what is their relationship to normal science?"

12.4 If the quotation will take more than four lines on the page, use indentation instead of quotation marks to indicate that the passage is a quotation. Introduce the quotation with a colon, set it off from the rest of the text by triple-spacing (assuming the rest of the text is double-spaced), indent ten spaces from the left margin, and single-space the quoted passage. To indicate a new paragraph within the quoted material, indent an additional three spaces.

12.5 Do not use quotation marks with indirect discourse, or with rhetorical, unspoken, or imaginary questions:

Frank said he was sorry he couldn't be here.

Why am I doing this? she wondered.

13. Punctuating Quotations

13.1 Do not use a comma to mark the end of a quoted sentence that is followed by an identifying tag if the quoted sentence ends in a question mark or an exclamation point:

"Get out!" he screamed.

13.2 Commas and periods go inside closing quotation marks; semicolons and colons go outside the closing quotation marks:

Peter's response was "Money is no object," but the lawyer was still unwilling to accept his case.

The senator announced, "I will not seek reelection"; then he left the room.

13.3 Place a question mark or an exclamation point inside the closing quotation marks only if it belongs to the quotation rather than to the larger sentence:

Lenin's question was "What is to be done?" Should the U.S. support governments that it considers "moderately repressive"?

Wherever you use the question mark or exclamation point, do not use a period with it (see 18.1).

13.4 Use square brackets to enclose interpolations, corrections, or comments in a quoted passage. In journalism, use parentheses ( ) for this purpose.

14. Introducing Indented Quotations, Vertical Lists, and Formulas

The punctuation immediately following the introduction to an indented quotation, vertical list, or formula is determined by the grammatical structure of the introduction. Essentially, you should follow the same rules described in section 3 and section 1.2 even though the material you're introducing is set off from the rest of the sentence.

14.1 If the introduction is a main clause (a clause that could stand by itself as a complete sentence), follow it with a colon:

Each member of the expedition was asked to supply the following equipment:

· a sleeping bag

· a mess kit

· a propane stove

· a backpack

14.2 If the introductory element is not a main clause, follow it with a comma if one is required by the rule given in section 1.2:

According to Gene Fowler, "Writing is easy: all you do is sit staring at a blank sheet of paper until the drops of blood form on your forehead."

14.3 If the introduction is not a main clause and a comma is not required by the rule given in section 1.2, follow it with no punctuation at all:

In Philosophy and Physics, Werner Heisenberg points out that "The change in the concept of reality manifesting itself in quantum theory is not simply a continuation of the past; it seems to be a real break in the structure of modern science."

14.4 If you're uncomfortable with an unpunctuated introduction, try converting it into a main clause and using a colon:

In Philosophy and Physics, Werner Heisenberg makes the following observation about the effect of quantum theory on modern science:

15. Punctuating Vertical Lists

15.1 The items in an vertical list may be preceded by sequential numbers or bullets (usually dots or asterisks), or they may stand alone. Depending on their grammatical structure, the items are followed by periods, semicolons, commas, or no punctuation at all. The Chicago Manual of Style offers the following simple rules: "Omit periods after items in a vertical list unless one or more of the items are complete sentences. If the vertical list completes a sentence begun in an introductory element, the final period is also omitted unless the items in the list are separated by commas or semi-colons."

The following minerals are included in this daily supplement:

niacin

iron

potassium

calcium

phosphorus

After six months of deliberation, the committee decided

1. that the proposed research did not pose a serious health hazard to the surrounding community;

2. that the potential benefits of the research significantly outweighed the potential risks; and

3. that the research should be allowed to proceed without further delay.

16. Question Marks

16.1 Use a question mark at the end of an interrogative element within (as well as at the end of) a sentence:

He asked himself, "How am I going to pay for all of this?" and looked hopefully at his father.

17. Exclamation Points

17.1 Use exclamation points sparingly; too many of them will dull your effect (compare 9.1).

18. Multiple Punctuation

18.1 In most cases, when two marks of punctuation are called for at the same location in a sentence, only the stronger mark is used (see, for example, 13.3). An abbreviating period, however, is never omitted unless the abbreviation is immediately followed by a terminating period. Other exceptions include 5.1c.

CONCLUSION

Brief outline of the most characteristic features of the five language styles and their variants will show that out of the member of features which are easily discernible in each of the styles, some should be considered primary and others secondary, some obligatory, others optional, some constant, others transitory. One of the five language styles is A PROSE style.

In this Course paper we have investigated:

1. The stylistic features of functional styles

2. The linguistic features of functional styles.

3. Language peculiarities of English PROSE style.

4. Language peculiarities of a substyle of PROSE style- otatorical one.

Functional style is thus to be regarded as the product of a certain concrete task set by the sender of the message. Functional styles appear mainly in the literary standard of a language. Each functional style may be characterized by a number of distinctive features leading or subordinate, constant or changing, obligatory pr optional. Each functional style subdivided into a number of substyles. Each variety has basic features common to all the varieties of the given function style and peculiar features typical of this variety alone. Still a substyle can, in some cases, deviate so far from the invariant that in its extreme it may even break away.

The oratorical s ty l e of language is the oral subdivision of the publicistic style. It has already been pointed out that persuasion is the most obvious purpose of oratory.

Direct contact with the listeners permits a combination of the syntactical, lexical and phonetic peculiarities of both the written and spoken varieties of language. In its leading features, however, oratorical style belongs to the written variety of language, though it is modified by the oral form of the utterance and the use of gestures. Certain typical features of the spoken variety of speech present in this style are: direct address to the audience (ladies and gentlemen, honourable member(s), the use of the 2nd person pronoun you, etc.), sometimes contractions I’ll, won't, haven't, isn't and,others) and the use of colloquial words.

This style is evident in speeches on political and social problems of the day, in orations and addresses on solemn occasions, as public weddings, funerals and jubilees, in sermons and debates and also in the speeches'of counsel and judges in courts of law.

THE LIST OF THE USED LITERATURE

1. Linda Jorgensen. Real-World Newsletters (1999)

2. Mark Levin. The Reporter's Notebook : Writing Tools for Student Journalists (2000)

3. Allan M. Siegal and William G. Connolly. The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage: The Official Style Guide Used by the Writers and Editors of the World's Most Authoritative Newspaper, (2002)

4. M. L. Stein, Susan Paterno, and R. Christopher Burnett, The Newswriter's Handbook Introduction to Journalism (2006)

5. Steve Peha and Margot Carmichael Lester, Be a Writer: Your Guide to the Writing Life (2006)

6. Andrea Sutcliffe. New York Public Library Writer's Guide to Style and Usage, (1994)

7. Crystal D. Investigating English Style. Longman’s 1969.

8. Galperin I.R. “Stylistics” M., 1977

9. Kukharenko V.A. “A book of practice in stylistics” M., 1986

10. “Essays on Style and language” Ed. by R. Towler. L., 1967

11. “Essays in Modern Stylistics” Ed. by D.C. Freeman. L – N.Y. 1981

[1] Linda Jorgensen. Real-World Newsletters (1999)

[2] Allan M. Siegal and William G. Connolly. The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage: The Official Style Guide Used by the Writers and Editors of the World's Most Authoritative Newspaper, (2002)

[3] Stilstudien, 1928, and Romanische Stil- und Literaturstudien, 1931

[4] www.stylistics.com

[5] Le Style des Pléiades de Gobineau (1957), "Criteria for Style Analysis" (1959) "Stylistic Context" (1960)

[6] Ferdinand de Saussure, Roman Jakobson

[7] Noam Chomsky Syntactic Structures, 1957

Похожие работы

... as in his defective stories, or terror, as is the case of “The Cask Of Amontillado”. Poe’s tales of terror are perhaps, more widely known to the general reader than his defective stories. Poe’s short narrative prose style as found in the two categories characteristic of his fiction has widely influenced the form and purpose of the short story, not only in the United States, but also around the ...

of promoting a morpheme is its repetition. Both root and affixational morphemes can be emphasized through repetition. Especially vividly it is observed in the repetition of affixational morphemes which normally carry the main weight of the structural and not of the denotational significance. When repeated, they come into the focus of attention and stress either their logical meaning (e.g. that of ...

... materials based on electric devices manuals are studied. In the next chapter lexical and grammatical peculiarities have been reviewed. 2. Lexical and grammatical peculiarities of scientific-technical texts In any scientific and technical text, irrespective of its contents and character, can be completely precisely translated from one language to other, even if in an artwork such branch of ...

ams, elegies, songs, satires and sermons. His poetry is noted for its vibrancy of language and inventiveness of metaphor, especially as compared to that of his contemporaries. John Donne's masculine, ingenious style is characterized by abrupt openings, paradoxes, dislocations, argumentative structure, and "conceits"--images which yoke things seemingly unlike. These features in combination with ...

0 комментариев