Íàâèãàöèÿ

The history of Old English and its development

In 409 AD the last Roman legion left British shores, and in fifty years the Islands became a victim of invaders. Germanic tribes from Southern Scandinavia and Northern Germany, pushed from their densely populated homelands, looked for a new land to settle. At that time the British Isles were inhabited by the Celts and remaining Roman colonists, who failed to organize any resistance against Germanic intruders, and so had to let them settle here. This is how the Old English language was born.

Celtic tribes crossed the Channel and starting to settle in Britain already in the 7th century BC. The very word "Britain" seems to be the name given by the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the island, accepted by first Indo-Europeans. The Celts quickly spread over the island, and only in the north still existed non-Indo-European peoples which are sometimes called "Picts" (the name given by Romans). Picts lived in Scotland and on Shetland Islands and represented the most ancient population of the Isles, the origin of which is unknown. Picts do not seem to leave any features of their language to Indo-European population of Britain - the famous Irish and Welsh initial mutations of consonants can be the only sign of the substratum left by unknown nations of Britain. At the time the Celts reached Britain they spoke the common language, close to Gaulish in France. But later, when Celtic tribes occupied Ireland, Northern England, Wales, their tongues were divided according to tribal divisions. These languages will later become Welsh, Irish Gaelic, Cornish, but from that time no signs remained, because the Celts did not invent writing yet. Not much is left from Celtic languages in English. Though many place names and names for rivers are surely Celtic (like Usk - from Celtic *usce "water", or Avon - from *awin "river"), the morphology and phonetics are untouched by the Celtic influence. Some linguists state that the word down comes from Celtic *dún "down"; other examples of Celtic influence in place names are tne following:

cothair

(a fortress) - Carnarvon

uisge (water) - Exe, Usk, Esk

dun,

dum (a hill) - Dumbarton, Dumfries, Dunedin

llan (church) -

Llandaff, Llandovery, Llandudno

coil (forest) - Kilbrook,

Killiemore

kil (church) - Kilbride, Kilmacolm

ceann (cape) -

Kebadre, Kingussie

inis (island) - Innisfail

inver (mountain)

- Inverness, Inverurie

bail (house) - Ballantrae, Ballyshannon,

and, certainly, the word whiskey which means the same as Irish

uisge "water". But this borrowing took place much later.

In the 1st century AD first Roman colonists begin to penetrate in Britain; Roman legions built roads, camps, founded towns and castles. But still they did not manage to assimilate the Celts, maybe because they lived apart from each other and did not mix. Tens of Latin words in Britain together with many towns, places and hills named by Romans make up the Roman heritage in the Old English. Such cities as Dorchester, Winchester, Lancaster, words like camp, castra, many terms of the Christian religion and several words denoting armaments were borrowed at that time by Britons, and automatically were transferred into the Old English, or Anglo-Saxon language already when there was no Romans in the country.

In 449 the legendary leaders of two Germanic tribes, Hengist and Horsa, achieved British shores on their ships. The Anglo-Saxon conquest, however, lasted for several centuries, and all this period Celtic aborigines moved farther and farther to the west of the island until they manage to fortify in mountainous Wales, in Corwall, and preserved their kingdoms in Scotland. Germanic tribes killed Celtic population, destroyed Celtic and former Roman towns and roads. In the 5th century such cities as Durovern in Kent, Virocon, Trimontii, Camulodunum, were abandoned by the population.

Angles settled around the present-day Noridge, and in Northern England; Saxons, the most numerous of the tribes, occupied all Central England, the south of the island and settled in London (Londinii at that time). Jutes and Frises, who probably came to Britain a bit later, settled on the island of White and in what is now Kent - the word Kent derives from the name of the Celtic tribe Cantii. Soon all these tribes founded their separate kingdoms, which was united after centuries of struggle only in 878 by Alfred, king of Wessex. Before that each of the tribes spoke its language, they were similar to each other but had differences which later became the dialectal peculiarities of Old English.

Now a little bit about the foreign influence in Old English. From the 6th century Christianity start activities in Britain, the Bible is translated into Old English, and quite a lot of terms are borrowed from Latin at that time: many bishops, missionaries and Pope's officials come from Rome. The next group of foreign loanwords were taken from Scandinavian dialects, after the Vikings occupied much of the country in the 9th - 11th centuries. Scandinavian languages were close relatives with Old English, so the mutual influence was strong enough to develop also the Old English morphology, strengthening its analytic processes. Many words in the language were either changed to sound more Scandinavian, or borrowed.

The Old English language, which has

quite a lot of literature monuments, came to the end after the Norman

conquest in 1066. The new period was called Middle English.

The Old English Substantive.

The substantive in Indo-European has always three main categories which change its forms: the number, the case, the gender. It ias known that the general trend of the Indo-European family is to decrease the number of numbers, cases and genders from the Proto-Indo-European stage to modern languages. Some groups are more conservative and therefore keep many forms, preserving archaic language traits; some are more progressive and lose forms or transform them very quickly. The Old English language, as well as practically all Germanic tongues, is not conservative at all: it generated quite a lot of analytic forms instead of older inflections, and lost many other of them.

Of eight Proto-Indo-European cases, Old English keeps just four which were inherited from the Common Germanic language. In fact, several of original Indo-European noun cases were weak enough to be lost practically in all branches of the family, coinciding with other, stronger cases. The ablative case often was assimilated by the genitive (in Greek, Slavic, Baltic, and Germanic), locative usually merged with dative (Italic, Celtic, Greek), and so did the instrumental case. That is how four cases appeared in Germanic and later in Old English - nominative, genitive, accusative and dative. These four were the most ancient and therefore stable in the system of the Indo-European morphology.

The problem of the Old English instrumental case is rather strange - this case arises quite all of a sudden among Germanic tongues and in some forms is used quite regularly (like in demonstrative pronouns). In Gothic the traces of instrumental and locative though can be found, but are considered as not more than relics. But the Old English must have "recalled" this archaic instrumental, which existed, however, not for too long and disappeared already in the 10th century, even before the Norman conquest and transformation of the English language into its Middle stage.

As for other cases, here is a little pattern of their usage in the Old English syntax.

1. Genitive - expresses the possessive menaing: whose? of what?

Also

after the expression meaning full of , free of , worthy of , guilty

of, etc.

2. Dative - expresses the object towards which the action is directed.

After the after the verbs like "say to smb", "send smb", "give to smb"; "known to smb", "necessary for smth / smb", "close to smb", "peculiar for smth".

Also

in the expressions like from the enemy, against the wind, on

the shore.

3. Accusative - expresses the object immediately affected by the action (what?), the direct object.

Three genders were strong enough, and only northern dialects could sometimes lose their distinction. But in fact the lose of genders in Middle English happened due to the drop of the case inflections, when words could no longer be distinguished by its endings. As for the numbers, the Old English noun completely lost the dual, which was preserved only in personal pronouns (see later).

All Old English nouns were divided into strong and weak ones, the same as verbs in Germanic. While the first had a branched declension, special endings for different numbers and cases, the weak declension was represented by nouns which were already starting to lose their declension system. The majority of noun stems in Old English should be referred to the strong type. Here are the tables for each stems with some comments - the best way of explaining the grammar.

a-stems

Singular

Nom. stán

(stone) scip (ship) bán (bone) reced

(house) níeten (ox)

Gen. stánes

scipes bánes

recedes

níetenes

Dat. stáne scipe báne recede

níetene

Acc. stán scip

bán reced

níeten

Plural

Nom. stánas

scipu

bán reced níetenu

Gen. stána scipa bána receda

níetena

Dat. stánum scipum bánum recedum níetenum

Acc. stánas

scipu

bán reced

níetenu

This type of stems derived from masculine and neuter noun o-stems in Proto-Indo-European. First when I started studying Old English I was irritated all the time because I couldn't get why normal Indo-European o-stems are called a-stems in all books on Old English. I found it a silly and unforgivable mistake until I understood that in Germanic the Indo-European short o became a, and therefore the stem marker was also changed the same way. So the first word here, stán, is masculine, the rest are neuter. The only difference in declension is the plural nominative-accusative, where neuter words lost their endings or have -u, while masculine preserved -as.

A

little peculiarity of those words who have the sound [æ] in the

stem and say farewell to it in the plural:

Masculine

Neuter

Sing. Pl.

Sing.

Pl.

N dæg

(day) dagas fæt (vessel) fatu

G dæges daga

fætes

fata

D dæge

dagum fæte fatum

A dæg

dagas fæt fatu

Examples of a-stems: earm (an arm), eorl, helm (a helmet), hring (a ring), múþ (a mouth); neuter ones - dor (a gate), hof (a courtyard), geoc (a yoke), word, déor (an animal), bearn (a child), géar (a year).

ja-stems

Singular

Masculine

Neuter

N hrycg (back) here (army) ende (end) cynn (kind) ríce (realm)

G hrycges

heriges endes cynnes ríces

D hrycge herige ende

cynne ríce

A hrycg here ende

cynn ríce

Plural

N hrycgeas herigeas endas

cynn ríciu

G hrycgea herigea enda

cynna rícea

D hrycgium herigum endum cynnum rícium

A hrycgeas herigeas

endas cynn ríciu

Again the descendant of Indo-European jo-stem type, known only in masculine and neuter. In fact it is a subbranch of o-stems, complicated by the i before the ending: like Latin lupus and filius. Examples of this type: masculine - wecg (a wedge), bócere (a scholar), fiscere (a fisher); neuter - net, bed, wíte (a punishment).

wa-stems

Singular Plural

Masc. Neut. Masc. Neut.

N bearu (wood) bealu (evil) bearwas bealu (-o)

G bearwes

bealwes bearwa bealwa

D bearwe bealwe bearwum

bealwum

A bearu (-o) bealu (-o) bearwas bealu (-o)

Just to mention. This is one more peculiarity of good old a-stems with the touch of w in declension. Interesting that the majority of this kind of stems make abstract nouns. Examples: masculine - snáw (snow), þéaw (a custom); neuter - searu (armour), tréow (a tree), cnéw (a knee)

ó-stems

Sg.

N swaþu (trace) fór (journey) tigol

(brick)

G swaþe fóre

tigole

D swaþe fóre

tigole

A swaþe fóre

tigole

Pl.

N swaþa

fóra

tigola

G swaþa

fóra

tigola

D swaþum fórum

tigolum

A swaþa

fóra

tigola

Another major group of Old English nouns consists only of feminine nouns. Funny but in Indo-European they are called a-stems. But Germanic turned vowels sometimes upside down, and this long a became long o. However, practically no word of this type ends in -o, which was lost or transformed. The special variants of ó-stems are jo- and wo-stems which have practically the same declension but with the corresponding sounds between the root and the ending.

Examples

of ó-stems:

caru

(care), sceamu

(shame), onswaru

(worry), lufu

(love), lár

(an instruction), sorg

(sorrow), þrág

(a season), ides

(a woman).

Examples of jó-stems:

sibb

(peace), ecg

(a blade), secg

(a sword), hild

(a fight), æx

(an axe).

Examples of wó-stems:

beadu (a

battle), nearu (need),

læs (a beam).

i-stems

Masc. Neut.

Sg.

N sige (victory) hyll (hill) sife (sieve)

G siges hylles sifes

D sige

hylle sife

A sige

hyll sife

Pl.

N sigeas

hyllas sifu

G sigea hylla sifa

D sigum

hyllum sifum

A sigeas hyllas sifu

The

tribes and nations were usually of this very type, and were used

always in plural: Engle

(the Angles), Seaxe

(the Saxons), Mierce

(the Mercians), Norþymbre

(the Northumbrians), Dene

(the Danish)

N Dene

G

Dena (Miercna, Seaxna)

D Denum

A Dene

Fem.

Sg. Pl.

N hyd (hide) hýde, hýda

G hýde

hýda

D hýde

hýdum

A hýd

hýde, hýda

This kind of stems included all three genders and derived from the same type of Indo-European stems, frequent also in other branches and languages of the family.

Examples: masculine - mere (a sea), mete (food), dæl (a part), giest (a guest), drync (a drink); neuter - spere (a spear); feminine - cwén (a woman), wiht (a thing).

u-stems

Masc.

Fem.

Sg.

N sunu (son)feld (field) duru (door) hand (hand)

G suna

felda dura

handa

D suna

felda dura

handa

A sunu

feld duru hand

Pl.

N suna

felda dura

handa

G suna

felda dura

handa

D sunum feldum

durum handum

A suna felda dura

handa

They can be either masculine or feminine. Here it is seen clearly how Old English lost its final -s in endings: Gothic had sunus and handus, while Old English has already sunu and hand respectively. Interesting that dropping final consonants is also a general trend of almost all Indo-European languages. Ancient tongues still keep them everywhere - Greek, Latin, Gothic, Old Prussian, Sanskrit, Old Irish; but later, no matter where a language is situated and what processes it undergoes, final consonants (namely -s, -t, often -m, -n) disappear, remaining nowadays only in the two Baltic languages and in New Greek.

Examples: masculine - wudu (wood), medu (honey), weald (forest), sumor (a summer); fem. - nosu (a nose), flór (a floor).

The other type of nouns according to their declension was the group of Weak nouns, derived from n-nouns is Common Germanic. Their declension is simple and stable, having special endings:

Masc. Fem. Neut.

Sg.

N nama (name) cwene (woman) éage (eye)

G naman

cwenan

éagan

D naman

cwenan

éagan

A naman

cwenan

éage

Pl.

N naman cwenan

éagan

G namena cwenena

éagena

D namum

cwenum éagum

A naman cwenan

éagan

Examples: masc. - guma (a man), wita (a wizard), steorra (a star), móna (the Moon), déma (a judge); fem. - eorþe (Earth), heorte (a heart), sunne (Sun); neut. - éare (an ear).

And now the last one which is interesting due to its special Germanic structure. I am speaking about the root-stems which according to Germanic laws of Ablaut, change the root vowel during the declension. In Modern English such words still exist, and we all know them: goose - geese, tooth - teeth, foot - feet, mouse - mice etc. At school they were a nightmare for me, now they are an Old English grammar. Besides, in Old English time they were far more numerous in the language.

Masc.

Fem.

Sg.

N mann fót (foot)

tóþ (tooth) | hnutu (nut) bóc (book) gós (goose) mús (mouse) burg (burg)

G mannes fótes

tóþes | hnute bóce góse

múse burge

D menn fét

téþ

| hnyte béc gés

mýs byrig

A mann fót tóþ

| hnutu bók gós

mús burg

Pl.

N menn fét téþ | hnyte béc

gés

mýs byrig

G manna fóta tóþa | hnuta bóca gósa músa

burga

D mannum fótum

tóþum | hnutum bócum

gósum músum burgum

A menn fét téþ | hnyte béc

gés

mýs

byrig

The general rule is the so-called i-mutation,

which changes the vowel. The conversion table looks as follows and

never fails - it is universally right both for verbs and nouns. The

table of i-mutation

changes remains above.

Examples: fem. - wífman

(a woman), ác

(an oak), gát

(a goat), bróc

(breeches), wlóh

(seam), dung

(a dungeon), furh

(a furrow), sulh

(a plough), grut

(gruel), lús

(a louse), þrul

(a basket), éa

(water), niht

(a night), mæ'gþ

(a girl), scrúd

(clothes).

There are still some other types of declension, but not too important fro understanding the general image. For example, r-stems denoted the family relatives (dohtor 'a daughter', módor 'a mother' and several others), es-stems usually meant children and cubs (cild 'a child', cealf 'a calf'). The most intriguing question that arises from the picture of the Old English declension is "How to define which words is which kind of stems?". I am sure you are always thinking of this question, the same as I thought myself when first studying Old English. The answer is "I don't know"; because of the loss of many endings all genders, all stems and therefore all nouns mixed in the language, and one has just to learn how to decline this or that word. This mixture was the decisive step of the following transfer of English to the analytic language - when endings are not used, people forget genders and cases. In any solid dictionary you will be given a noun with its gender and kind of stem. But in general, the declension is similar for all stems. One of the most stable differences of masculine and feminine is the -es (masc.) or -e in genitive singular of the Strong declension.

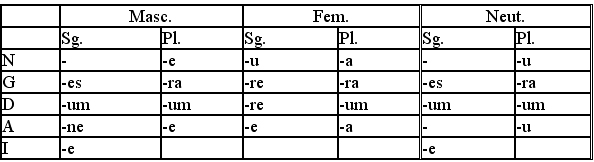

Now I am giving another table, the general declension system of Old English nouns. Here '-' means a zero ending.

Strong declension (a, ja, wa, ó, jó, wó, i -stems).

| Masculine | Neutral | Feminine | ||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | - | -as | - | -u (-) | - | -a |

| Genitive | -es | -a | -es | -a | -e | -a |

| Dative | -e | -um | -e | -um | -e | -um |

| Accustive | - | -as | - | -u (-) | -e | -a |

| Weak declension | u-stems | |||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | - | -an | - | -a |

| Genitive | -an | -ena | -a | -a |

| Dative | -an | -um | -a | -um |

| Accustive | -an | -an | - | -a |

The Old English Adjective.

In all historical Indo-European languages adjectives possess practically the same morphological features as the nouns, the the sequence of these two parts of speech is an ordinary thing in Indo-European. However, the Nostratic theory (the one which unites Altaic, Uralic, Semitic, Dravidian and Indo-European language families into one Nostratic super-family, once speaking a common Proto-Nostratic language) represented by Illych-Svitych and many other famous linguists, states that adjectives in this Proto-Nostratic tongue were morphologically closer to the verbs than to the nouns.

This theory is quite interesting, because even in Proto-Indo-European, a language which was spoken much later than Proto-Nostratic, there are some proofs of the former predicative function of the adjectives. In other families of the super-family this function is even more clear. In Altaic languages, and also in Korean and Japanese, which are originally Altaic, the adjective plays the part of the predicate, and in Korean, for example, the majority of adjectives are predicative. It means that though they always denote the quality of the noun, they act the same way as verbs which denote action. Adjective "red" is actually translated from Japanese as "to be red", and the sentence Bara-wa utsukusii will mean "the rose is beautiful", while bara is "a rose", -wa is the nominative marker, and utsukusii is "to be beautiful". So no verb here, and the adjective is a predicate. This structure is typical for many Altaic languages, and probably was normal for Proto-Nostratic as well.

The Proto-Indo-European language gives us some stems which are hard to denote whether they used to mean an adjective or a verb. Some later branches reflect such stems as verbs, but other made them adjectives. So it was the Proto-Indo-European epoch where adjectives as the part of speech began to transform from a verbal one to a nominal one. And all Indo-European branches already show the close similarity of the structure of adjectives and nouns in the language. So does the Old English language, where adjective is one of the nominal parts of speech.

As well as the noun, the adjective can be declined in case, gender and number. Moreover, the instrumental case which was discussed before was preserved in adjectives much stronger than in nouns. Adjectives must follow sequence with nouns which they define - thet is why the same adjective can be masculine, neuter and feminine and therefore be declined in two different types: one for masculine and neuter, the other for feminine nouns. The declension is more or less simple, it looks much like the nominal system of declension, though there are several important differences. Interesting to know that one-syllable adjectives ("monosyllabic") have different declension than two-syllable ones ("disyllabic"). See for yourselves:

Strong

Declension

a, ó-stems

Monosyllabic

Sg.

Masc.

Neut. Fem.

N blæc

(black) blæc blacu

G

blaces blaces blæcre

D blacum blacum blæcre

A blæcne blæc blace

I blace

blace -

Pl.

N blace

blacu blaca

G blacra blacra blacra

D blacum blacum blacum

A blace

blacu blaca

Here "I" means that very instrumental case, answering the question (by what? with whom? with the help of what?).

Disyllabic

Masc. Neut. Fem.

Sg.

N éadig (happy) éadig éadigu

G éadiges

éadiges éadigre

D éadigum éadigum éadigre

A éadigne

éadig éadige

I éadige

éadige

Pl.

N éadige éadigu éadiga

G éadigra

éadigra éadigra

D éadigum éadigum éadigum

A éadige éadigu éadigu

So not many new endings: for accusative singular we have -ne, and for genitive plural -ra, which cannot be met in the declension of nouns. The difference between monosyllabic and disyllabic is the accusative plural feminine ending -a / -u. That's all.

ja,

jó-stems (swéte

- sweet)

Sg. Pl.

Masc. Neut. Fem. Masc. Neut.

Fem.

N swéte

swéte swétu

swéte swétu swéta

G swétes swétes swétre swétra swétra swétra

D swétum

swétum swétre swétum

swétum swétum

A swétne swéte swéte

swéte swétu swéta

I swéte

swéte -

wa,

wó-stems

Sg.

Masc.

Neut. Fem.

N nearu (narrow) nearu

nearu

G nearwes

nearwes nearore

D nearwum nearwum nearore

A nearone nearu

nearwe

I nearwe nearwe

Pl.

N nearwe

nearu nearwa

G nearora

nearora nearora

D nearwum nearwum

nearwum

A nearwe nearu

nearwa

Actually, some can just omit all those examples - the adjectival declension is the same as a whole for all stems, as concerns the strong type. In general, the endings look the following way, with very few varieties (note that "-" means the null ending):

As for weak adjectives, they also exist in the language. The thing is that one need not learn by heart which adjective is which type - strong or weak, as you should do with the nouns. If you have a weak noun as a subject, its attributive adjective will be weak as well. So - a strong adjective for a strong noun, a weak adjective for a weak noun, the rule is as simple as that.

Thus if you say "a black tree" that will be blæc tréow (strong), and "a black eye" will sound blace éage. Here is the weak declension example (blaca - black):

Sg. Pl.

Masc.

Neut. Fem.

N blaca blace

blace blacan

G blacan blacan

blacan blæcra

D blacan blacan

blacan blacum

A blacan blace

blacan blacan

Weak declension has a single plural for all genders, which is pleasant for those who don't want to remeber too many forms. In general, the weak declension is much easier.

The last thing to be said about the adjectives is the degrees of comparison. Again, the traditional Indo-European structure is preserved here: three degrees (absolutive, comparative, superlative) - though some languages also had the so-called "equalitative" grade; the special suffices for forming comparatives and absolutives; suppletive stems for several certain adjectives.

The suffices we are used to see in Modern English, those -er and -est in weak, weaker, the weakest, are the direct descendants of the Old English ones. At that time they sounded as -ra and -est. See the examples:

earm

(poor) - earmra - earmost

blæc (black)

- blæcra - blacost

Many adjectives changed the root vowel - another example of the Germanic ablaut:

eald

(old) - ieldra - ieldest

strong - strengra - strengest

long - lengra - lengest

geong

(young) - gingra - gingest

The most widespread and widely used adjectives always had their degrees formed from another stem, which is called "suppletive" in linguistics. Many of them are still seen in today's English:

gód

(good) -

betera - betst (or sélra

- sélest)

yfel

(bad) - wiersa - wierest

micel

(much) - mára - máést

lýtel

(little) - læ'ssa - læ'st

fear

(far) - fierra - fierrest, fyrrest

néah (near)

- néarra - níehst,

nýhst

æ'r

(early) -

æ'rra - æ'rest

fore

(before) - furþra - fyrest

(first)

Now you see what the word "first" means - just the superlative degree from the adjective "before, forward". The same is with níehst from néah (near) which is now "next".

Old English affixation for adjectives:

1.

-ede

(group "adjective stem + substantive stem") - micelhéafdede

(large-headed)

2. -ihte

(from substantives with mutation) - þirnihte

(thorny)

3. -ig

(from substantives with mutation) - hálig

(holy), mistig

(misty)

4. -en, -in

(with mutation) - gylden

(golden), wyllen

(wóllen)

5. -isc

(nationality) - Englisc, Welisc,

mennisc (human)

6. -sum

(from stems of verbs, adjectives, substantives) - sibbsum

(peaceful), híersum

(obedient)

7. -feald

(from stems of numerals, adjectives) - þríefeald

(threefold)

8. -full

(from abstract substantive stems) - sorgfull

(sorrowful)

9. -léás

(from verbal and nominal stems) - slæpléás

(sleepless)

10. -líc

(from substantive and adjective stems) - eorþlíc

(earthly)

11. -weard

(from adjective, substantive, adverb stems) - inneweard

(internal), hámweard

(homeward)

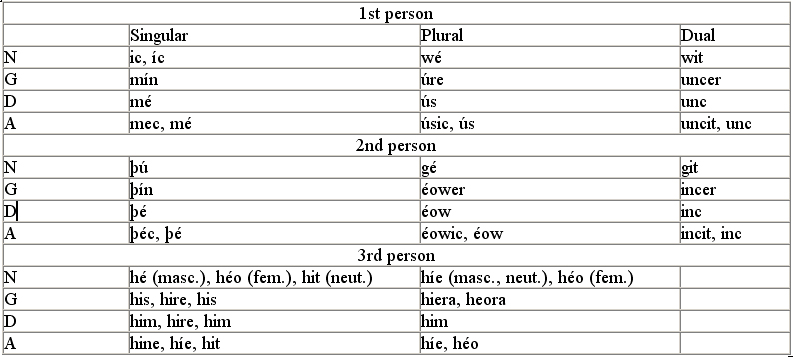

The Old English Pronoun.

Pronouns were the only part of speech in Old English which preserved the dual number in declension, but only this makes them more archaic than the rest parts of speech. Most of pronouns are declined in numnber, case and gender, in plural the majority have only one form for all genders.

We will touch each group of Old English pronouns and comment on them.

1.Personal

pronouns

Through the last 1500 years mín became mine, gé turned into you (ye as a colloquial variant). But changes are still significant: the 2nd person singular pronouns disappeared from the language, remaining only in poetic speech and in some dialects in the north of England. This is really a strange feature - I can hardly recall any other Indo-European language which lacks the special pronoun for the 2nd person singular (French tu, German du, Russian ty etc.). The polite form replaced the colloquial one, maybe due to the English traditional "ladies and gentlemen" customs. Another extreme exists in Irish Gaelic, which has no polite form of personal pronoun, and you turn to your close friend the same way as you spoke with a prime minister - the familiar word, translated into French as tu. It can sound normal for English, but really funny for Slavic, Baltic, German people who make a thorough distinction between speaking to a friend and to a stranger

Ïîõîæèå ðàáîòû

... mean, however, that the grammatical changes were rapid or sudden; nor does it imply that all grammatical features were in a state of perpetual change. Like the development of other linguistic levels, the history of English grammar was a complex evolutionary process made up of stable and changeable constituents. Some grammatical characteristics remained absolutely or relatively stable; others were ...

... . 6. The Scandinavian element in the English vocabulary. 7. The Norman-French element in the English vocabulary. 8. Various other elements in the vocabulary of the English and Ukrainian languages. 9. False etymology. 10.Types of borrowings. 1. The Native Element and Borrowed Words The most characteristic feature of English is usually said to be its mixed character. Many linguists ...

... Smirnitsky 2). He added to Skeat's classification one more criterion: grammatical meaning. He subdivided the group of perfect homonyms in Skeat's classification into two types of homonyms: perfect which are identical in their spelling, pronunciation and their grammar form, such as «spring» in the meanings: the season of the year, a leap, a source, and homo-forms which coincide in their spelling ...

... : the Suiones (Swedes) in the north Svealand; and the Gothones (Goths), in the south (hence called Gothia). CONCLUSION The importance of a language is inevitably associated in the mind of the world with the political role played by the nations using it and their influence in international affairs; with the confidence people feel in their financial position and the certainty with which ...

0 êîììåíòàðèåâ