Íàâèãàöèÿ

Communication The Exchange of Information

MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION

OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN

GULISTAN STATE UNIVERSITY

The English and Literature Department

Qualification work on speciality English philology

on the theme:

“Communication. The Exchange of Information”Supervisor: ___________

Gulistan 2008

CONTENTS:

I. Introduction

Message oriented communication.

II. The Main Body

Language Learning Principles

The nature of speaking and oral interaction

Communicative approach and language teaching.

Chapter I.

Types of communicative exercises and approaches.

Warming up exercises

Interiews

Jigsaw tasks

Chapter II.

Questioning activities

Values clarification techniques

Thinking strategies

Interactive problem solving

Chapter III.

Stories and poetry – painting that speaks

Games as a way at breaking the routine of classroom drill

Project work as a natural extension of content based instruction (CIB)

III. Conclusion

Some Practical Techniques for Language Teaching

Bibliography

Introduction

Message oriented communication

I want you to communicate. This means that I want you to understand others and to make yourself understandable to them. These sound like the obvious goals of every language learner., but I think these simple goals need to be emphasized, because learners too often get diverted from them and fall into more of a struggle with the mechanics of grammar and pronunciation that they should. Learners can become timid about using what they know for fear of making horrible mistakes with what they don’t know. All the attention paid to the mechanics of communication sometimes gets in the way of communication itself.

In the early lessons of many language courses, students are encouraged to concentrate heavily upon pronunciation and grammar, while vocabulary is introduced only very slowly. The idea seems to be that even if one has very little to say, that little bit should be said correctly. Students can worry a great deal about the machinery of language, but they worry rather little about real communicating much of anything. Under such circumstances, learners have to think about an awful lot of things in order to construct even a simple sentence. They are supposed to force their mouths to produce sounds that seem ridiculous. They have to grope desperately for words that they barely know. They have to perform mental gymnastic trying to remember bizarre grammatical rules. All these challenges are a fatal distraction from what skillful speakers worry about – the message that they want to convey. If early learners have to worry about getting everything correct, they cannot hope to day anything very interesting. They simply cannot do everything at once and emerge with any real sense of success.

In the German original 'mttteilungsbezogene Kommunikation was coined by Black and Butzkamm (1977)[1]. They use it to refer to those rare and precious moments in foreign language teaching when the target language is actually used to arrange communication. À prime instance of this use is classroom discourse, i.e. getting things done in the lesson. Sometimes real communicative situations develop spontaneously, as in exchanging comments on last night' s TV programme or introduction someone' s new haircut. The majority of ordinary language teaching situations before reaching an advanced level, however, are geared towards language-oriented communication or what Rivers calls 'skill-getting': they make use of the foreign language mainly in structural exercises and predetermined responses by the learners. Since foreign language teaching should help students achieve some kind of communicative skill in the foreign language, àll situations in which real communication occurs naturally have to be taken advantage of and many more suitable ones have to be created.

Two devices help the teacher in making up communicative activities: information gap and opinion gap. Information-gap exercises force the participants to exchange information in order to find a solution (e.g. reconstitute a text, solve a puzzle, write a summary). Problem-solving activities. Opinion gaps are created by exercise or program controversial texts or ideas, which require the participants to describe and perhaps defend their views on these ideas. Another type of opinion- gap activity can be organised by letting the participants share their feelings about an experience they have in common. Furthermore, learning a foreign language is not just a matter of memorising a simple set of names for the things around us; it is also an educational experience. Since our language is closely linked with our personality and culture, why not use the process of acquiring a new language to gain further insights into our personality and culture? This does not mean that students of a foreign language should submit to psychological exercises or probing interviews, but simply that, for example, learning to talk about their likes and dislikes and bring about a greater awareness of their values and aims in life. Many of the activities are concerned with the learners themselves. For learners who are studying English in a non-English-speaking setting it is very important to experience real communicative situation in which they learn to express their own views and attitudes, and in which they are taken seriously as people.

As applying the principles of information gap and opinion gap to suitable traditional exercises the teacher can change them into more challenging communicative situations. Thus the well-known procedure at beginner's level of having students describe each other's appearance is transformed into a communicative activity as soon as an element of guessing (information gap) is introduced. However, not all exercises can be spruced up like this. Manipulative drills that have no real topic have to remain as they are. Information and opinion-gap exercises have to hav some content worth talking about. Students do not want to discuss trivia; the interest which is aroused by the structure of the activity may be reduced or increased by the topic.

Many of the activities are concerned with the learners themselves. Their feelings and ideas are the focal point of these exercises, around which a lot of their foreign language activity revolves. For learners who are studying English in a non-English-speaking setting it is very important to experience real communicative situation in which they learn to express their own views and attitudes, and in which they are taken seriously as people. Traditional textbook exercises — however necessary and useful they may be for all- communicative grammar practice — do not as a rule forge a link between the learners and the foreign language in such a way that the learners identify with it. Meaningful activities on a personal level can be a step towards this identification, which improves performance and generates interest. And, of course, talking about something which affects them personally is eminently motivating for students.

Furthermore, learning a foreign language is not just a matter of memorising a simple set of names for the things around us; it is also an educational experience. Since our language is closely linked with our personality and culture, why not use the process of acquiring a new language to gain further insights into our personality and culture? This does not mean that students of a foreign language should submit to psychological exercises or probing interviews, but simply that, for example, learning to talk about their likes and dislikes and bring about a greater awareness of their values and aims in life. À number of activities. adapted from 'values clarification' theory have been included with this purpose in mind.

Learning is very effective if the learners are actively involved in the process. The degree of learner activity depends, among other things, on the type of material they are working on. The students' curiosity can be aroused by texts or pictures containing discrepancies or mistakes, or by missing or muddled information, and this curiosity leads to the wish to find out, to put right or to complete. Learner activity in a more literal sense of the word can also imply doing and making things; for example, producing a radio programme forces the students to read, write and talk in the foreign language as well as letting them learn with tape recorders, sound effects and music. Setting up an opinion poll in the classroom is a second, less ambitious vehicle for active learner participation; it makes students interview each other, it literally gets them out of their seats and — this is very important — it culminates in a final product which everybody has helped to produce.

Activities for practising a foreign language have left the narrow path of purely structural and lexical training and have expanded into the fields of values education and personality building. The impact of foreign language learning on the shaping of the learner' s personality is slowly being recognised. That is why foreign language teaching — just like many other subjects — plays an important part in education towards cooperation and empathy. As teachers we would like our students to be sensitive towards the feelings of others and share their worries and joys. À lot of teaching/learning situations, however, never get beyond a rational and fact-oriented stage. That is why it seems important to provide at least a few instances focusing on the sharing ideas. igsaw tasks, in particular, demonstrate to the learners that cooperation is necessary. Many of the activities included in this book focus on the participants' personalities and help build an atmosphere of mutual understanding.

Quite an important factor in education towards cooperation is the teacher's attitude. If she favours a cooperative style of teaching generally and does not shy away from the greater workload connected with group work or projects, then the conditions for learning to teachers are good. The atmosphere within a class or group can largely be determined by the teacher, who- quite often without being aware of it — sets the tone by choosing certain types of exercises and topics.

This section deals with the importance of the atmosphere within the class or group, the teacher's role, and ways of organising discussions, as well as giving hints on the selection and use of the activities in class.

À lot of the activities will run themselves as soon as they get under way. The teacher then has tî decide whether to join in the activity as an equal member (this may sometimes be unavoidable for pair work in classes with an odd number of students) or remain in the background to help and observe. The first alternative has à number of advantages: for example the psychological distance between teacher and students may bå reduced when students get tî know their teacher better. Of course, the teacher has to refrain from continually correcting the students or using her greater skill in the foreign language tî her advantage. If the teacher joins in the activity, she will then nî longer be able to judge independently and give advice and help to other groups, which is the teacher's major role if she does not participate directly. À further advantage of non-participation is that the teacher may unobtrusively observe the performance of several students in the foreign language and note common mistakes for revision at à later stage. À few activities, mainly jigsaw tasks, require the teacher to withdraw completely from the scene.

Whatever method is chosen, the teacher should be careful not to correct students' errors too frequently. Being interrupted and corrected makes the students hesitant and insecure in their speech when they should really be practising communication. It seems far better for the teacher to use the activities for observation and ñî help only when help is demanded bó the students themselves; even then they should be encouraged to overcome their difficulties by finding alternative ways of expressing what they want tî say. There is à list of speech acts which may bå needed for the activities and the relevant section may be duplicated and given as handouts to help the students.

Many of the activities are focused on the individual learner. Students are asked to tell the others about their feelings, likes or dislikes. They are also asked to judge their own feelings and let themselves bå interviewed by others. Speaking about oneself is not something that everyone does with ease. It becomes impossible, even for the most extrovert person, if the atmosphere in the group is hostile and the learner concerned is afraid of being ridiculed or mocked. The first essential requirement for the use of learner-centred activities (they are marked pers. in all the tables) is à relaxed and friendly atmosphere in the group. Only then can the aims of these activities be achieved: cooperation and the growth of understanding.

Groups or classes that have just been formed or are being taught by à new teacher may not develop this pleasant kind of group feeling immediately. In that case activities dealing with very personal topics should be avoided. The teacher may stimulate à good atmosphere by introducing both warming-up exercises and jigsaw tasks. Even in à class where the students know each other well, certain activities may take on threatening features for individual students. In order tî avoid any kind of embarrassment or ill feeling, the teacher should say that anyone may refuse to answer à personal question without having to give any reason or explanation. The class have ñî accept this refusal without discussion or comment. Although I have tried to steer clear of I threatening activities, there may still be à few which fall into this category for very shy students. In any case teachers should be able to select activities which their students will feel at ease with. As à rough guideline teachers øght ask themselves whether they would be prepared to participate fully in the activity themselves.

À number of different ways of setting up the communicative activities in this book are explained in the description of the activities themselves. For teachers who would like to change their procedures for handling classroom discussions (å.g. in connection with topical texts) à few major types are described below:

Buzz groups[2]. À problem is discussed in small groups for à few minutes before views or solutions are reported to the whole class.Hearing. 'Experts' discuss à topical question and màó be interviewed by à panel of students who then have to make à decision about that question.

Fishbowl. All the members of the class sit in à big circle. In the middle of the circle there are five chairs. Three are occupied by students whose views (preferably controversial) on the topic or question are known beforehand. These three start the discussion. They màó be joined by one or two students presenting yet another view. Students from the outer circle màó also replace speakers in the inner circle by tapping them on the shoulder if they feel confident that they can present the case better.

Network The class is divided into groups which should not have mîrå than 10 students each. Each group receives à ball of string. Whoever is speaking on the topic chosen holds the ball of string. When the speaker has finished he gives the ball of string to the next speaker, but holds on to the string. In this way à web of string develops, showing who talked the most and who the least.

Onion. The class is divided into two equal groups. As many chairs as there are students are arranged in à double circle, with the chairs in the outer circle facing inwards and those of the inner circle facing outwards. Thus each member of the inner circle sits facing à student in the outer circle. After à few minutes of discussion all the students in the outer circle move on one chair and now have à new partner rî continue with.

Star. Four to six small groups try and find à common view or solution. Each group elects à speaker who remains in the group but enters into discussion with the speakers of the other groups.

Market. All the students walk about the rîîm; each talks to several others.

The Main Body

Language Learning Principles

Language learning principles for mainstream classes. Hutchinson and Waters[3] (1997:128) present eight language learning principles in relation to a learner-centered methodology. A learner-centered methodology need not exist only in a language classroom, and much language learning takes place outside of the language classroom. Hutchinson and Waters relate the learning principles to the ESP classroom, but often these EAL (English as an Additional Language) learners are in classes that are not taught by language experts, and therefore the classes are not remembered as a rich resource for language input.

The discussion on teaching techniques is not meant for language experts only. I have used the principles as a point of departure for discussions on language across the curriculum seminars. These seminars often concern department or campus-wide staff who are not well informed on language issues. Perhaps teachers are intimidated by the thought of fostering language development in the classroom because they equate the notion with grammar rules. The eight (language) learning principles are outlined below along with a discussion of their teaching implications and how they are to be applied to teaching beyond the language classroom.

1. Second language learning is a developmental process. In other words, learners use existing knowledge to make the incoming information comprehensible. Gagne and Bridges (1988)[4] discuss "external" and "internal" conditions of learning in much the same way. The example they use is understanding when the U.S. presidential elections take place: the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November, every four years. In order to truly grasp this "external" knowledge (when the elections take place), they explain that a learner must have certain "internal" conditions in place, i.e., the knowledge of the days of the week, and the months in the year, etc. This example may seem too simple to be applicable at the tertiary level, but one can easily imagine how concepts and ideas in a field are made understandable by building on some existing knowledge.

The teaching implications of this principle are that lecturers should reconsider what, if anything, they have been taking for granted concerning their students' knowledge base. The knowledge that each student brings to the classroom is likely to be just as diverse. Do the lecturers adapt the presentation to the "internal" knowledge of the student? In other words, is there ample opportunity given in class to discover what learners understand about the concept being taught? As an example, how is the idea of "perfectly competitive market" explained in an economics class filled with EAL learners? Do learners know what "competitive" means? If they have indeed heard the words, what types of understanding do they have? It is quite possible that "market" for some of the students here in South Africa simply means a fruit and vegetable stand or maybe even what is commonly known in the U.S. as a "flea market" (a number of stalls selling various items ranging from food to crafts). The definition of perfect competition, "a large number of relatively small price-taking firms that produce a homogenous product and for whom entry and exit are relatively costless" (Dillingham et al 1992:250)[5] means nothing for the students if they are unaware of the more basic components of the concept. The components which comprise a concept should be carefully elicited from the students and addressed if necessary.

Students should be given prompts as much as possible. These could take the form of visual aids, handouts, or even words and concepts written on the board. By hearing and seeing the language, the students are better able to match the concepts and terminology to their internal knowledge, and thus be better equipped to add the external information if possible. This suggestion may sound painfully easy or remedial, but many learners, especially language learners, need to see the information as it is being discussed.

2. Language learning is an active process. The learners must actively use the new information. This is easier said than done. In terms of language learning, this means practising the vocabulary and grammar with great frequency for it to be internalized. With this principle in mind, many language classes at the tertiary level in the U.S. are time-tabled for maximum contact time (five hours a week), whereas the "content" subjects average three hours a week. The thinking behind this imbalance is related to the unlikelihood that the learner will have contact with the language outside the classroom.

What can a mainstream lecturer do with a majority of students for whom English is not their mother tongue? The principle of frequency, however, is the same: Revise the information. According to Hamilton and Ghatala (1994:118)[6], elaboration is the key to getting information into long-term memory. By elaboration, the authors mean working with the same information in different but related ways. Examples of elaboration techniques are: summarizing, outlining, mind-mapping, drawing pictures, using metaphors, eliciting examples for learners, etc. In ESP, the terms, concepts, and definitions are new and unfamiliar to students. According to Gagne and Briggs (1988). repetition is the key to retention.

Students often struggle with the information conveyed orally, and perhaps the fact that they are struggling is partly due to the way the information is conveyed and partly due to their level of language proficiency and cognitive ability. Written material is another obstacle, but at least one can take ones time with the reading and consult a dictionary or peers to make some sense of it.

3. Language learning is a decision-making process. Typically, teachers do all the talking and making of decisions in the classroom. The teacher is the knower of the information, so it is considered more efficient for him/her to present the material. But efficient in what way? For the lecturer, no doubt, it is easy to walk into class, deliver the information, and leave. What about the students? Hutchin-son and Waters (1987:129) argue that in order to develop, learners must use existing knowledge, make decisions based on that knowledge, and see results.

This means that learners need to go through a processing step, both internally and externally: internally to formulate decisions, and externally to test those decisions. Externally, the learner would express his/her ideas and receive feedback

External processing implies a move away from summative evaluation to formative evaluation. Learners should demonstrate their knowledge often and if possible be credited for it. To wait until the end of term not only puts more pressure on the students in terms of the "all or nothing" mark, it also leaves the facilitator to estimate what percentage of the lecture material is being internalized during the term. Summative evaluation for first year students might also promote a culture of passiveness or idleness. Checking understanding frequently with mini-tasks, quizzes, or worksheets is beneficial in a number of ways: It gives the facilitator an idea of what is being internalized by the students, and it gives the students reinforcement of the material as well as motivation to attend class (accountability).

4. Language learning is not just a matter of linguistic knowledge. The premise here is that there is more to comprehension, production, and learning in general than the words themselves. A learner may be cognizant of each individual word due to a good vocabulary base, but not understand the ideas expressed in them because of a lack of cognitive development. The reverse could also be true with a student having the cognitive capacity or background to understand the concepts, but not the linguistic ability to respond successfully. As a result, language learners are often inaccurately perceived as being cognitively and conceptually slow, when in fact it might well be their linguistic ability that is lagging.

In the end, many lecturers of these typical second language learners base their judgment of students solely on their surface ability to communicate orally and in writing. If the student is poor in communication due to grammatical errors, that is often where the line is drawn and the mark given. Conversely, a lecturer is often lenient in marking because s/he understands more or less what the learner is getting at even if the message is not clearly conveyed.

5. Language learning is not the learner's first experience (with language). The students are generally competent in another language, and in terms of subject-specific information, they might have some knowledge of the concepts or terminology. A classroom should tap into these competencies and help the learners transfer them from one language (or experience) to another, or activate the existing knowledge to aid in the understanding of the new information.

Hutchinson at all (1987:140) suggests getting the students to predict before reading or listening. Having students predict is advantageous for two reasons: It sets the students' schema (or road map) of the subject, i.e., the internal knowledge, thereby getting it ready to attach to external knowledge, as discussed in connection with principle three above, and it informs the lecturer as to what knowledge the students already possess. A lecturer then will be able to target the session accordingly, spending time on concepts that are not clearly known, and only reviewing those that are.

In terms of teaching, schema-setting can take the form of a brief review of the day's class lesson, pre-reading, pictures, drawing, diagrams, charts, discussions, anecdotes, etc. The function of assigning readings before a lecture serves the schema-setting purpose. However, one needs to bear in mind the level of language used throughout the passage as well as the length of the passage.

6. Language learning is an emotional experience. This principle concerns the affective filter of the student, or variables related to motivation, attitude, anxiety, and self-confidence. The condition of these variables, according to Dulay and Burt (in Oller 1993:32)[7], determines what information is internalised. Students can be fragile entities. They can easily be intimidated, resulting in debilitating effects. The key then is to create a relaxed and non-threatening atmosphere in the classroom for optimal learning. To make the learning more positive, Hutchinson and Waters (1987:129) suggest a number of ways of being sensitive to affective filters:

• Use pair work or group work to build social relationships;

• Give students time to think, and generally avoid undue pressure;

• Put less emphasis on the product (the right answer) and more on the process of getting an answer;

• Value attitude as much as aptitude and ability;

• Make "interest," "fun," and "variety" primary considerations in materials and methodology, rather than just added extras.

Fun and games should not be excluded from study. Fun and games do not preclude learning. Activities can still be fun and challenging and thereby cater to those students for whom pressure is a stimulant. Using pair and group work in the class has numerous advantages; it provides the following opportunities:

• Students get to know other students;

• Students form study groups or join with partners;

• Instructors see progress in class and "test" student knowledge and input;

• Variety is brought into the classroom;

• Pressure for individuals is reduced;

• Students work with the concepts and terminology actively rather than being passive-listeners;

In addition, using pair and group work takes some of the pressure off the instructor in terms of constant "performance," gives the students some independent learning skills practice, and at the same time allows the instructor to observe the "intake" of learners. Following this observation, instructors can provide specific input where necessary.

7. Language learning is to a large extent incidental. One does not need to be actively studying language to learn language. English (or Afrikaans) is the medium through which students learn the content, but the language itself does not need to be the focus. The content subject lecturers would not suddenly be required to explain grammatical rules to the class, but writing down vocabulary and terminology would be appropriate for a class with a majority of second language speakers. The focus would not be taken off the content, but the lecturer should be sensitive to the medium of instruction, should slow down the presentation, should provide visual aids, and should repeat and revise often. These are not radical measures to adapt teaching to a varied student population, but they are helpful.

8. Language learning is not systematic. Although information is stored systematically, the process by which it is assimilated is not necessarily systematic. Each learner has a preferred method of learning, and within a classroom, any combination of learning styles could be represented: visual, auditory, tactile, and kinesthetic. Davis and Nur (1994)[8] discuss various learning style inventories used to determine a student's preferred style of learning: cognitive, affective, and psy-chomotor. Briefly, cognitive inventories determine how a person takes in information: what problem-solving strategies are used and how they classify and sequence information. Affective inventories determine a student's motivation for learning and what factors influence this motivation. Finally, psychomotor inventories show learner preferences for subject matter and mode of presentation. The point of conducting such inventories is to discover the students' preferred learning styles and to match the teaching style to achieve optimal learning in the classroom.

Maybe not so surprising is the idea that listening passively to a lecture is not the most successful mode for learning, but it remains the most common in terms of transmission. Simply adding visuals to a lecture will benefit both the visual and auditory learners. Adding an activity that uses some type of handout will address the tactile learner. Having the students get up and change seats for group work or a jigsaw activity will give the kinesthetic learners some stimulation.

Clearly it is not possible to match all learners' needs to one instructional style. However, alternating the mode of "transmission" will provide an opportunity for all styles of learning to be modeled, give students a chance to become familiar with different strategies, and allow for a varied classroom.

These principles outlined from Hutchinson and Waters all focus on the learner. Although the principles are from a language book, they can be used easily in any subject to address learning in general and learning in a language other than one's home language.

The language teaching principles discussed and the implications drawn from them are meant to suggest ways in which instructors can integrate language in their classroom to reinforce anything from vocabulary to thinking and social skills in the form of group and pair work.

The approach based on the principles outlined above might be very new to both learners and instructors. Fortunately, one does not need to employ them all at once to reap the benefits. A learner-centered approach promotes a culture of active learning and, hopefully, leads to greater confidence and empowerment of the student.

The nature of speaking and oral interaction

Brown and Yule (1983)[9] begin their discussion on the nature of spoken language by distinguishing between spoken and written language. They point out that for most of its history, language teaching has been concerned with the teaching of written language. This language is characterised by well-formed sentences which are integrated into highly structured paragraphs. Spoken language, on the other hand, consists of short, often fragmentary utterances, in a range of pronunciations. There is often a great deal of repetition and overlap between one speaker and another, and speakers frequently use non-specific references (they tend to say 'thing', 'it' and 'this' rather than 'the left-handed monkey wrench', or 'the highly perfumed French poodle on the sofa'). Brown and Yule point out that the loosely organised syntax, the use of non-specific words and phrases and the use of fillers such as 'well', 'oh' and 'uhuh' make spoken language feel less conceptually dense than other types of language such as expository prose. They suggest that, in contrast with the teaching of written language, teachers concerned with teaching the spoken language must confront the following types of questions:

What is the appropriate form of spoken language to teach?

—From the point of view of pronunciation, what is a reasonable model?

—How important is pronunciation?

—Is it any more important than teaching appropriate handwriting in the foreign language?

—If so, why?

—From the point of view of the structures taught, is it all right to teach the spoken language as if it were exactly like the written language, but with a few 'spoken expressions' thrown in?

—Is it appropriate to teach the same structures to all foreign language students, no matter what their age is or their intentions in learning the spoken language?

—Are those structures which are described in standard grammars the structures which our students should be expected to produce when they speak English?

—How is it possible to give students any sort of meaningful practice in producing spoken English?

Brown and Yule also draw a useful distinction between two basic language functions. These are the transactional function, which is primarily concerned with the transfer of information, and the interactional function, in which the primary purpose of speech is the maintenance of social relationships.

Another basic distinction we can make when considering the development of speaking skills is between monologue and dialogue. The ability to give an uninterrupted oral presentation is quite distinct from interacting with one or more other speakers for transactional and interactional purposes. While all native speakers can and do use language interactionally, not all native speakers have the ability to extemporise on a given subject to a group of listeners. This is a skill which generally has to be learned and practised. Brown and Yule suggest that most language teaching is concerned with developing skills in short, interactional exchanges in which the learner is only required to make one or two utterances at a time. They go on to state that: .. . the teacher should realise that simply training the student to produce short turns will not automatically yield a student who can perform satisfactorily in long turns. It is currently fashionable in language teaching to pay particular attention to the forms and functions of short turns. ... It must surely be clear that students who are only capable of producing short turns are going to experience a lot of frustration when they try to speak the foreign language.

Communicative Approach and LanguageTeacing

All the "methods" described so far are symbolic of the progress foreign language teaching ideology underwent in the last century. These were methods that came and went, influenced or gave birth to new methods - in a cycle that could only be described as "competition between rival methods" or "passing fads" in the methodological theory underlying foreign language teaching. Finally, by the mid-eighties or so, the industry was maturing in its growth and moving towards the concept of a broad "approach" to language teaching that encompassed various methods, motivations for learning English, types of teachers and the needs of individual classrooms and students themselves. It would be fair to say that if there is any one "umbrella" approach to language teaching that has become the accepted "norm" in this field, it would have to be the Communicative Language Teaching Approach. This is also known as CLT.

The Communicative approach does a lot to expand on the goal of creating "communicative competence" compared to earlier methods that professed the same objective. Teaching students how to use the language is considered to be at least as important as learning the language itself. Brown (1994) aptly describes the "march" towards CLT:

"Beyond grammatical discourse elements in communication, we are probing the nature of social, cultural, and pragmatic features of language. We are exploring pedagogical means for 'real-life' communication in the classroom. We are trying to get our learners to develop linguistic fluency, not just the accuracy that has so consumed our historical journey. We are equipping our students with tools for generating unrehearsed language performance 'out there' when they leave the womb of our classrooms. We are concerned with how to facilitate lifelong language learning among our students, not just with the immediate classroom task. We are looking at learners as partners in a cooperative venture. And our classroom practices seek to draw on whatever intrinsically sparks learners to reach their fullest potential."

CLT is a generic approach, and can seem non-specific at times in terms of how to actually go about using practices in the classroom in any sort of systematic way. There are many interpretations of what CLT actually means and involves. See Types of Learning and The PPP Approach to see how CLT can be applied in a variety of 'more specific' methods.

From the remarks already made, it should be obvious that the current interest in tasks stems largely from what has been termed 'the communicative approach' to language teaching. In this section I should like to briefly sketch out some of the more important principles underpinning communicative language teaching.

Although it is not always immediately apparent, everything we do in the classroom is underpinned by beliefs about the nature of language and about language learning. In recent years there have been some dramatic shifts in attitude towards both language and learning. This has sometimes resulted in contradictory messages to the teaching profession which, in turn, has led to confusion.

Among other things, it has been accepted that language is more than simply a system of rules. Language is now generally seen as a dynamic resource for the creation of meaning. In terms of learning, it is generally accepted that we need to distinguish between 'learning that' and 'knowing how'. In other words, we need to distinguish between knowing various grammatical rules and being able to use the rules effectively and appropriately when communicating.

This view has underpinned communicative language teaching (CLT). A great deal has been written and said about CLT, and it is something of a misnomer to talk about 'the communicative approach' as there is a family of approaches, each member of which claims to be 'communicative' (in fact, it is difficult to find approaches which claim not to be communicative!). There is also frequent disagreement between different members of the communicative family.

During the seventies, the insight that communication was an integrated process rather than a set of discrete learning outcomes created a dilemma for syllabus designers, whose task has traditionally been to produce ordered lists of structural, functional or notional items graded according to difficulty, frequency or pedagogic convenience. Processes belong to the domain of methodology. They are somebody else's business. They cannot be reduced to lists of items. For a time, it seems, the syllabus designer was to be out of business.

One of the clearest presentations of a syllabus proposal based on processes rather than products has come from Breen. He suggests that an alternative to the listing of linguistic content (the end point, as it were, in the learner's journey) would be to prioritize the route itself; a focusing upon the means towards the learning of a new language. Here the designer would give priority to the changing process of learning and the potential of the classroom — to the psychological and social resources applied to a new language by learners in the classroom context. ... a greater concern with capacity for communication rather than repertoire of communication, with the activity of learning a language viewed as important as the language itself, and with a focus upon means rather than predetermined objectives, all indicate priority of process over content.

(Breen 1984: 52-3)[10]

What Breen is suggesting is that, with communication at the centre of the curriculum, the goal of that curriculum (individuals who are capable of using the target language to communicate with others) and the means (classroom activities which develop this capability) begin to merge; the syllabus must take account of both the ends and the means.

What then do we do with our more formal approaches to the specification of structures and skills? Can they be found a place in CLT? We can focus on this issue by considering the place of grammar.

For some time after the rise of CLT, the status of grammar in the curriculum was rather uncertain. Some linguists maintained that it was not necessary to teach grammar, that the ability to use a second language (knowing 'how') would develop automatically if the learner were required to focus on meaning in the process of using the language to communicate. In recent years, this view has come under serious challenge, and it now seems to be widely accepted that there is value in classroom tasks which require learners to focus on form. It is also accepted that grammar is an essential resource in using language communicatively.

This is certainly Littlewood's view. In his introduction to communicative language teaching, he suggests that the following skills need to be taken into consideration:

—The learner must attain as high a degree as possible of linguistic

competence. That is, he must develop skill in manipulating the

linguistic system, to the point where he can use it spontaneously

and flexibly in order to express his intended message.

—The learner must distinguish between the forms he has mastered

as part of his linguistic competence, and the communicative

functions which they perform. In other words, items mastered as

part of a linguistic system must also be understood as part of a

communicative system.

—The learner must develop skills and strategies for using language

to communicate meanings as effectively as possible in concrete

situations. He must learn to use feedback to judge his success,

and if necessary, remedy failure by using different language.

—The learner must become aware of the social meaning of

language forms. For many learners, this may not entail the

ability to vary their own speech to suit different social circumstances, but rather the ability to use generally acceptable forms and avoid potentially offensive ones.

(Littlewood 1981: 6)[11]

At this point, you might like to consider your own position on this matter. Do you think that considerations of content selection and grading (i.e. selecting and grading grammar, functions, notions, topics, pronunciation, vocabulary etc.) should be kept separate from the selection and grading of tasks, or not? As we have already pointed out, we take the view that any comprehensive curriculum needs to take account of both means and ends and must address both content and process. In the final analysis, it does not really matter whether those responsible for specifying learning tasks are called 'syllabus designers' or 'methodologists'. What matters is that both processes and outcomes are taken care of and that there is a compatible and creative relationship between the two.

Whatever the position taken, there is no doubt that the development of communicative language teaching has had a profound effect on both methodology and syllabus design, and has greatly enhanced the status of the learning 'task' within the curriculum.

Students need to be understood and to be able to say what they want to say. Their pronunciation should be at least adequate for that purpose. They need to know the various sounds that occur in the language and differentiate between them. They should be able to apply certain rules, eg. past tense endings, t, d or id. Likewise, a knowledge of correct rhythm and stress and appropriate intonation is essential.

In Extract 1, the teacher plays the part of ringmaster. He asks the questions (most of which are 'display' questions which require the learners to provide answers which the teacher already knows). The only student-initiated interaction is on a point of vocabulary.

• In the second extract, the learners have a much more active role. They communicate directly with each other, rather than exclusively with the teacher as is the case in Extract 1, and one student is allowed to take on the role of provider of content. During the interaction it is the learner who is the 'expert' and the teacher who is the 'learner' or follower.

From time to time, it is a good idea to record and analyse interactions in your own classroom. These interactions can either be between you and your students, or between students as they interact in small-group work. If you do, you may be surprised at the disparity between what you thought at the time was happening, and what actually took place as recorded on the tape. You should not be disconcerted if you do find such a disparity. In my experience, virtually all teachers, even the most experienced, discover dimensions to the lesson which they were unaware of at the time the lesson took place. (These will not all be negative, of course.)

The raw data of interaction, as above, are often illuminating. The following reactions were provided by a group of language teachers at an inservice workshop. The teachers had recorded, transcribed and analysed a lesson which they had recently given and were asked (among other things) to report back on what they had discovered about their own teaching, and about the insights they had gained into aspects of classroom management and interaction. Most of the comments referred, either explicitly or implicitly, to teacher/learner roles:

'As teachers we share an anxiety about "dominating" and so a common assumption that we are too intrusive, directive etc.' 'I need to develop skills for responding to the unexpected and exploit this to realise the full potential of the lesson.' 'There are umpteen aspects which need improving. There is also the effort of trying to respond to contradictory notions about teaching (e.g. intervention versus non-intervention).' 'I had been making a conscious effort to be non-directive, but was far more directive than I had thought.'

'Using small groups and changing groups can be perplexing and counterproductive, or helpful and stimulating. There is a need to plan carefully to make sure such changes are positive.' 'I have come to a better realisation of how much listening the teacher needs to do.' 'The teacher's role in facilitating interaction is extremely important for all types of classes. How do you teach teachers this?' 'I need to be more aware of the assumptions underlying my practice.' 'I discovered that I was over-directive and dominant.' 'Not to worry about periods of silence in the classroom.' 'I have a dreadful tendency to overload.' 'I praise students, but it is rather automatic. There is also a lot of teacher talk in my lessons.' 'I give too many instructions.' 'I discovered that, while my own style is valuable, it leads me to view issues in a "blinkered" way. I need to analyse my own and others' styles and ask why do I do it that way?'

Chapter I

Types of communicative exercises

Warming-up exercises

When people have to work together in à group it is advisable that they get to know each other à little at the beginning. Încå they have talked tî each other in an introductory exercise they will be less reluctant to cooperate in further activities. One of the pre-requisites of cooperation is knowing the other people's names. À second one is having some idea of what individual members of the group are interested in. One important use of warming-up exercises is with new classes at the beginning of à course or the school year. If óîè join in the activities and let the class know something about yourself, the students are mîrå likely to accept you as à person and not just as à teacher. À second use of warming-up activities lies in getting students into the right mood before starting on some new project or task.

However, even warming-up activities màó seem threatening to very shy students. In particular, exercises in which one person has to speak about himself in front of the whole class belong in this category. You can reduce the strain by reorganising the activity in such à way that the student concerned is questioned by the class, thus avoiding à monologue where the pressure is on one person only. Students often find pair work the least threatening because everybody is talking at the same time and they have only got one listener. Depending on the atmosphere in your classes, you màó wish tî modify whole-class exercises to include pair or group work.

À number of warming-up exercises, are also suitable for light relief between periods of hard work. Grouping contains à lot of ideas for dividing students into groups and can precede all types of group work.

Most of the warming-up exercises are suitable for beginners because they do not demand more than simple questions and answers. But the language content of the exercises can easily be adapted to à higher level of proficiency.

Names

Aims: Skills — speaking

Language — questions

Other — getting tî know each other' s names

Level: Beginners

Organisation: Class

Preparation : As many small slips of paper as there are students

Time : 5-10 minutes

Procedure : Step 1: Each student writes his full name on à piece of paper. All the papers are collected and redistributed sî that everyone receives the name of à person he does not know.

Step 2: Everyone walks around the room and tries to find the person whose name he holds. Simple questions can bå asked, å.g. 'Is your name...?' 'Are you...?'

Step 3: When everyone has found his partner, he introduces him tî the group[12].

Interviews

We watch, read and listen to interviews every day. In the media the famous and not sî famous are interviewed on important issues and trivial subjects. For the advertising industry and market research institutes, interviews are à necessity. The success of an interview depends both on the skill of the interviewer, on her ability to ask the right kinds of questions, to insist and interpret, and on the willingness to talk on the part of the person being interviewed. Both partners in an interview should be good at listening so that à question-and-answer sequence develops into à conversation.

In the foreign language classroom interviews are useful not only because they force students rî listen carefully but also because they are sî versatile in their subject matter.[13] As soon as beginners know the first structures for questions (å.g. Can you sing an English song? Have you got à car?) interviewing can begin. If everyone interviews his neighbour all students are practising the foreign language at the same time. When the learners have acquired à basic set of structures and vocabulary the interviews mentioned in this section can be used. À list of possible topics for further interviews is given at the end of the section. Of course, you may choose any topic you wish, taking them from recent news stories or texts read in class. In the warming-up phase of à course interviews could concentrate on more personal questions.

Before you use an interview in your class make sure that the students can use the necessary question-and-answer structures. À few sample sentences on the board may be à help for the less able. With advanced learners language functions like insisting and asking for confirmation (Did you mean that...? Do you really think that...? Did you say... ? But you said earlier that...), hesitating (Well, let me see...), contradicting and interrupting (Hold on à minute..., Can I just butt in here?) can be practised during interviews. When students report back on interviews they have done, they have to use reported speech.

Since the students' chances of asking à lot of questions are not very good in 'language-oriented' lessons, interviews are à good compensation. If you divide your class up into groups of three and let two students interview the third, then the time spent on practisinig questions is increased. As à rule students should make some notes on the questions they are going to ask and of the answers they get.

Self-directed interviews

Aims: Skills — writing, speaking

Language - questions

Other — getting tî know each other or each other' s points of view

Level : Intermediate

Organisation: Pairs

Preparation: None

Time: 10-30 minutes

Procedure:

Step 1: Each student writes down five to ten questions that he would like tî be asked. The general context of these questions can be left open, or the questions can be restricted to areas such as personal likes and dislikes, opinions, information about one' s personal life, åtñ.

Step 2: The students choose partners, exchange question sheets and interview one another using these questions.

Step 3: It might be quite interesting to find out in à discussion with the whole class what kinds of questions we asked and why they were chosen.

Variations Instead of fully written-up questions each student specifies three to five topics he would like tî bå asked about, å.g. pop music, food, friends.

Remarks: This activity helps to avoid embarrassment because nobody has to reveal thoughts and feelings he does not want to talk about.

Jigsaw tasks

Jigsaw tasks use the same basic principle as jigsaw puzzles with one exception. Whereas the player doing à jigsaw puzzle has all the pieces he needs in front of him, the participants in à jigsaw task have only one (or à few) piece(s) each. As in à puzzle the individual parts, which may be sentences from à story or factual text, or parts of à picture or comic strip, have tî be fitted together to find the solution. In jigsaw tasks each participant is equally important, because each holds part of the solution. That is why jigsaw tasks are said tî improve cooperation and mutual acceptance within the group[14]. Participants in jigsaw tasks have to do à lot of talking before they are able to fit the pieces together in the right way. It is obvious that this entails à large amount of practice in the foreign language, especially in language functions like suggesting, agreeing and disagreeing, determining sequence, etc. À modified form of jigsaw tasks is found in communicative exercises for pair work.

Jigsaw tasks practise two very different areas of skill in the foreign language. Firstly, the students have tî understand the bits of information they are given (i.å. listening and/or reading comprehension) and describe them to the rest of the group. This makes them realise how important pronunciation and intonation are in making yourself understood. Secondly, the students have to organise the process of finding the solution; à lot of interactional language is needed here. Because the language elements required by jigsaw tasks are not available at beginners' level, this type of activity is best used with intermediate and more advanced students. In à number of jigsaw tasks in this section the participants have to give exact descriptions of scenes or objects, so these exercises can be valuable for revising prepositions and adjectives.

Pair or group work is necessary for à number of jigsaw tasks. If your students have not yet been trained to use the foreign language amongst themselves in situations like these, there may be à few difficulties with monolingual groups when you start using jigsaw tasks. Some of these difficulties may be overcome if exercises designed for pair work are first done as team exercises so that necessary phrases can be practised.

The worksheets are also meant as stimuli for your own production of worksheets. Suitable drawings can be found in magazines. If you have à camera you can take photographs for jigsaw tasks, i.å. arrangements of à few objects with the positions changed in each picture. Textual material for strip stories can be taken from textbooks and text collections.

Some of the problem-solving activities are also à kind of jigsaw task.

The same or different?

Aims Skills — speaking, listening comprehension

Language — exact description

Other — cooperation

Level Intermediate

Organisation Class,Pairs

Preparation One copy each of handout À for half the students, and one ñîðó each of handout S for the other half (see Part 2)

Mimå 15-20

Procedure Step 1: The class is divided into two groups of equal size and the chairs arranged in two circles, the inner circle facing outwards, the outer circle facing inwards, so that two students from opposite groups sit facing each other. All the students sitting in the inner circle receive handout À. All the students in the outer circle receive handout S. They must not show each other their handouts.

Step 2: Each handout contains 18 small drawings; some are the same in À and S, and some are different. By describing the drawings to each other and asking questions the two students in each pair have to decide whether the drawing is the same or different, and mark it S or D. The student who has à cross next to the number of the drawing begins by describing it to his partner. After discussing three drawings all the students in the outer circle move to the chair on their left and continue with à new partner.

Step 3: When all the drawings have been discussed, the teacher tells the class the answers.

Variations The material can be varied in many ways. Instead of pictures, other things could be used, å.g. synonymous and non- synonymous sentences, symbolic drawings, words and drawings.

Chapter II

Questioning activities

This last section in the chapter is something of à mixed bag, in so far as it contains àll those activities which, although they centre around questioning, do not fit into any of the previous sections. First of all there are humanistic exercises that focus on the learners themselves, their attitudes and values. Secondly there is à kind of exercise that could be employed to teach learners about the cultural background of the target country. Thirdly there is à board game. Last of all there are three activities suitable either as warming-up exercises or as strategies for tackling more factual topics. The worksheets belonging tî these exercises can be modified accordingly. Many of these activities are quite flexible, not only as regards their content but also in terms of procedure. By simply introducing à few new rules, å.g. à limit on the number of questions or a time-limit they are transformed into games.

As soon as students are able to produce yes/no and wh-questions most of these activities can be used. You may, however, have ñî adapt the worksheets as these are not always aimed at the earliest stage at which an exercise can be used. For reasons of motivation similar activities, like Gî and find out and Find someone who..., should not be done directly one after the other[15].

For activities which question forms are practised. The book by Moskowitz (1978) contains à great number of humanistic exercises.

What would happen if...?[16]

Aims Skills — speaking

Language — if-clauses, making conjectures, asking for confirmation

Other — imagination

Level Intermidiate

Organisation Class

Preparation About twice as many slips of paper with an event/situation written on them as there are students

Time 10-15 minutes

Procedure Every student receives one or two slips of paper with sentences like these on them: 'What would happen if à shop gave away its goods free every Wednesday?' 'What would you do if you won à trip for two to à city of your choice?' One student starts by reading out his question and then asks another student to answer it. The second student continues by answering or asking à third student tî answer the first student's question. If he has answered the question he may then read out his own question for somebody else to answer. The activity is finished when all the questions have been read out and answered.

Variations The students can prepare their own questions. Some more suggestions:

What would happen

if everybody who told à lie turned green?

if people could get à driving licence at 14? if girls had to do military service?

if men were not allowed to become doctors or pilots? if children over 10 were allowed to vote? i f gold was found in your area?

if à film was made in your school/place of work?

if headmasters had to be elected by teachers and pupils? if smoking was forbidden in public places?

if the price of alcohol was raised by 300 per cent?

What would you do

if you were invited tî the Queen' s garden party?

if à photograph of yours won first prize at an exhibition? if your little sister aged 14 told you she was pregnant? if you saw your teacher picking apples from her neighbour' tree?

if à salesman called at your house and tried ñî sell you à sauna bath?

if your horoscope warned you against travelling when you want to go on holiday?

if it rained every day of your holiday?

if you got à love letter from somebody you did not know? if you found à snake under your bed?

if you got lost on à walk in the woods?

if you were not able to remember numbers?

if somebody hit à small child very hard in your presence? if you found à 120 note in à library book?

if your friend said she did not like the present you had given her?

if you suddenly found out that you could become invisible by eating spinach?

if you broke an expensive vase while you were baby-sitting at à friend' s house?

if you invited somebody to dinner at your house but they forgot to come?

if you forgot you had asked four people to lunch and didn' t have any food in the house when they arrived?

if à young man came up to you, gave you à red rose and said that you were the loveliest person he had seen for à long time?

if you noticed that you hadn' t got any money on you and you had promised tî ring your mother from à call box at exactly this time?

if you could not sleep at night?

Values clarification techniques

The àñtivitites in this section are based on the principle of the 'values clarification approach' which originated in the USA[17]. It is one of the assumptions of this approach that school must help young people to become aware of their own values and to act according tî them. The psychologist Louis Raths distinguishes between three main stages in this process: 'Prizing one' s beliefs and behaviours,... choosing one' s beliefs and behaviours,... acting on one' s beliefs’[18]. Personal values relate both to one' s own personality and to the outside world, including such areas as school, leisure activities or politics. Adults as well as young people may not always be consciously aware of their beliefs and so learners of all ages may find that the activities in this section help them tî discover something about themselves.

The activities in this section mainly concern the prizing and choosing of values; acting on one's beliefs cannot be learnt sî easily in the foreign language class. The individual tasks appeal directly tî the learners, who have to be prepared tî talk about their feelings and attitudes. On the one hand this may be à very motivating experience, because the students feel that they are communicating about something meaningful, as well as being taken seriously as people; on the other hand à situation in which the participants have to reveal some of their more 'private' thoughts màó appear threatening. Thus it is essential tî do these exercises in à supportive and relaxed atmosphere. You màó help create this atmosphere by joining in some of the exercises and sharing your values with óîur students. You should also remind your students of the guideline that nobody has tî answer embarrassing questions, and that the right to refuse to answer is granted to everyone in these exercises. The educational bias of values clarification techniques makes it easier to integrate them into à democratic style of teaching than mîrå traditional teacher- centred methods.

As regards the language items practised in these exercises, speech acts like expressing likes and dislikes, stating one' s opinions and giving/asking for reasons occur throughout. Skills like note taking are also practised, because students are often asked tî jot down their ideas and feelings.

Values clarification techniques share some characteristics with ranking exercises, but the latter are more structured and predictable.

Personalities

Aims Skills — speaking, writing

Language — descriptive sentences, past tense (reported speech)

Other — acknowledging the influence other people have on us, note taking

Level Intermdiate

Organisation Individuals, class

Preparation None

Time 10-30

Procedure Step 1: The students are asked tî think about their lives and the people they know/have known. Each student should find at least two people who have influenced him in his life. These màó be his parents, other relations, friends, or personalities from history or literature. Íå should note down some points in order to be able tî tell the rest of the class briefly how these people have influenced him.

Step 2: Each student in turn says à few sentences about these people. À discussion and/or question may follow each speal

Remarks Emphasis should be given to positive influences.

Lifestyle

Aims Skills — speaking

Language — giving reasons, stating likes and dislikes

Other — thinking about one' s priorities

Level Beginners/intermediate

Organisation Pairs

Preparation Students are asked à day or so beforehand ñî bring along three objects which are important or significant for them.

Time 10 — 15 minutes

Procedure Step 1: Students work with à partner. Each of them explains the use/purpose of the three objects he has brought with him and says why they are important and significant for him.

Both partners then talk about similarities and differences between their choice of objects.

Step 2: À few of the students present their partner's objects and explain their significance to the rest of the group.

Variations 1: Instead of real objects, drawings or photographs (cut out-3 of magazines or catalogues) may be used.

2: Before the paired discussion starts, à kind of speculating or guessing game can be conducted, where the three objects of à student whose identity is not revealed are shown, and suggestions about their significance are made.

Thinking strategies

In the last decade Edward de Bono has repeatedly demanded that thinking should be taught in schools. His main intention is to change our rigid way of thinking and make us learn to think creatively. Some of the activities in this section are taken from his thinking course for schools. Brainstorming, although also mentioned by de Bono, is à technique that has been used widely in psychology and cannot be attributed to him.

The thinking strategies resemble each other in that different ideas have to be collected by the participants in the first stage. In the second stage these ideas have tî be ordered and evaluated. It is obvious that there is ample opportunity tî use the foreign language at both stages. Apart from the speech acts of agreeing and disagreeing, suggesting, etc. these exercises practise all forms of comparison and the conditional.

Brainstorming

Aims Skills — speaking, writing

Language — conditional, making suggestions

Other — imagination, practice of important thinking skills

Level Intermediate

Organisation Groups of four to seven students

Preparation None

Time 5 — 15 minutes

Procedure Step 1: The class is divided into groups. Each group receives the same task. Possible tasks are:

(à) How many possible uses can you find for à paper clip (plastic bag/wooden coat hanger/teacup/pencil/sheet of typing paper/matchbox, etc.)?

(b) You have ñî make an important phone call but you have ïî change. How many ways can you find of getting the money for the call?

(ñ) How many ways can you find of opening à wine bottle without à corkscrew?

(d) How many ways can you find of having à cheap holiday? The groups work on the task for à few minutes, collecting as many ideas as possible without commenting on them or evaluating them. All the ideas are written down by the group secretary.

Step 2: Each group reads out their list of ideas. The ideas are written on the board.

Step 3: The groups choose five ideas from the complete list (either the most original or the most practical ones) and rank them.

Variations 1: After Step 1 the groups exchange their lists of ideas. Each group ranks the ideas on its new list according ñî à common criterion, å.g. practicability, costs, simplicity, danger, etc.

2: Each group chooses an idea and discusses it according to the procedure.

Remarks Brainstorming increases mental flexibility and encourages original thinking. It is à useful strategy for à great number of teaching situations.

Interactive problem solving

In this section, we shall look at two approaches in which communicative tasks are sequenced around problem situations. The first is Scarcella's sociodrama, while the second is Di Pietro's strategic interaction. Both approaches allow the teacher to build in exercises which enable learners to develop vocabulary, grammar and discourse as well as interactive skills.

The focus of Scarcella's sociodrama is on the development of skills in social interaction. Unlike most role plays, sociodrama involves a series of specific steps. It is student- rather than teacher-centred in that students define their own roles and determine their own course of action. The following set of steps provides an idea of how the approach works.

1. Warm up

The topic is introduced by the teacher.

2. Presentation of new vocabulary

New words and expressions are introduced.

3. Presentation of dilemma

A story is introduced by the teacher who stops at the dilemma point. Students focus on the conflict which occurs at the dilemma point.

4. Discussion of the situation and selection of roles

The problem and roles are discussed. Students who relate to the roles and who have solutions to offer come to the front of the class to participate in the enactment.

5. Audience preparation

Those who are not going to take part in the enactment are given specific tasks to carry out during the enactment.

6. Enactment

Role-players act out the solution which has been suggested.

7. Discussion of the situation and selection of new role-players

Alternative ways of solving the problem are explored and new

role-players are selected.

8. Re-enactment

The problem situation is replayed with new strategies.

9. Summary

The teacher guides the students to summarise what was presented.

10. Follow-up

These may include a written exercise, extended discussion, aural comprehension exercises or a reading exercise. (Scarcella 1978)[19]

Di Pietro's approach, which he calls 'strategic interaction' is based on improvisations or 'scenarios'. Students act out scenarios, having first memorised the situation and roles they are expected to play and having carefully rehearsed the scenario. However, at certain points during the acting out, additional information is injected into the situation, requiring learners to modify their intended role, and to alter the direction of the interaction.

With a little thought, problem situations and scenarios can be developed which do allow learners to rehearse 'real-world' language i.e. language they might potentially need to use in the real world. Whether or not a given lesson appears to have a real-world rationale really depends on the situation which the teacher has chosen. Scarcella obviously believes that her approach has real-world applications as can be seen in the following quote:

Socio-drama is an activity which obliges students to attend to the verbal environment. First, it is relevant to the students' interests, utilizing both extrinsic motivation, which refers to the students' daily interests and cares, and intrinsic motivation, which refers to the students' internal feelings and attitudes. . . . Furthermore, socio-drama is a problem-solving activity which stimulates real life situations and requires active student involvement.

(Scarcella 1978: 46)

In the following activities the learners have to find solutions tî various types of problem. In the case of puzzles there is just one correct solution: however, most of the åõårcises lead tî à discussion of several ways of solving the problems. The problem tasks themselves range from the imaginary to the more realistic. The latter provide situations which the learners might conceivably have . to face outside the classroom.

Apart from the activities focusing on the likes and dislikes of individual learners, which therefore need an initial phase where each student works on his own, most of the problem- '. solving tasks in this section require pair or group work throughout. In some ways these activities are similar to ranking exercises because, like them, they generate discussions of the importance or relevance of statements, ideas or procedures. But unlike ranking exercises, problem-solving activities demand that the learners themselves decide upon the items to be ranked. Thus there is more creative use of the foreign language. It is advisable to use the less complex ranking exercises before any problem- solving activities if the students have not done this kind of work before.

The language which is needed for problem-solving activities depends on the topic of each exercise, but in general students will have tî make suggestions, give reasons, and accept, modify or reject suggestions and reasons given by others.

Desert island

Aims Skills — speaking, writing

Language — giving and asking for reasons, agreeing and disagreeing, making suggestions

Other — imagination, common sense, fun

Level Intermediate

Organisation Individuals, pairs, groups.

Preparation None

Time 10-20

Procedure Step 1: The teacher describes the task tî the students: 'You are stranded on à desert island à long way from anywhere. There is à fresh water spring on the island, and there are banana trees and coconut palms. The climate is mild. Make à list of eight to twelve things which you think are necessary for survival.' Students work on their own.

Step 2: Students pair up and compare lists. They agree on à common list of à maximum of ten items.

Step 3: The students discuss the new lists in groups of four tî six students. They decide on à group list of à maximum of eight items and rank these according to their importance.

Rescue

Aims Skills — speaking

Language – stating an opinion, giving and asking for reasons, agreeing and disagreeing, comparisons

Other — thinking about one' s values

Level Intermediate/advanced

Organisation Groups of five to eight students

Preparation None

Time 10-20

Procedure Step 1: The teacher explains the situation:

'The Earth is doomed. All life is going tî perish in two due tî radiation. À spaceship from another solar system lands and offers to rescue twelve people, who could start à new world on an empty planet very much like Earth. Imagine you are the selection committee and you have to decide who màó be rescued. Think of à list of criteria which you would use in your decision.'

Step 2: Each group discusses the problem and tries to work out à list.

Step 3: Each group presents its list of criteria to the class. The lists are discussed.

Variations The task can be made mîrå specific, å.g. 'Find ten criteria. You can award up tî 100 points if à candidate gets full marks on all counts, å.g. appearance 5, intelligence 30, fertility 15, physical fitness 20, etc.

Remarks Although the basic problem is à rather depressing one, it helps students to clarify their own values as regards judging others.

Chapter III

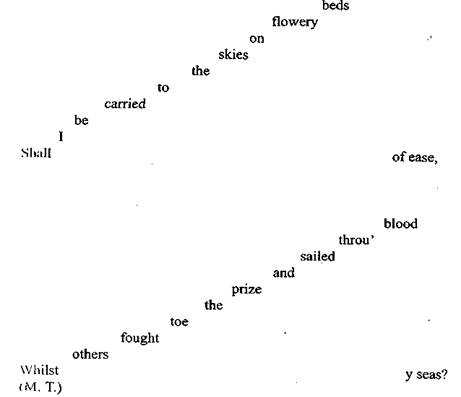

Stories & Poetry– painting that speaks[20]

The aim of these activities is to get the students to produce longer connected texts. For this they will need imagination as well as some skill in the foreign language. Stimuli are given in the form of individual words or pictures.

Story-telling activates more than à limited number of patterns and structures and these activities are best used as general revision.

Chain story[21]

Aims Skills — speaking

Language — simple past

Other — imagination, flexibility

Level Beginners/intermediate

Organisation Class

Preparation Small slips of paper with one noun/verb/adjective on each of them, as many pieces of paper as there are students

Time 10 — 20 minutes

Procedure Step 1: Each student receives à word slip.

Step 2: The teacher starts the story by giving the first sentence, å.g. 'It was à stormy night in November. À student (either à volunteer or the person sitting nearest to the teacher) continues the story. Íå màó say up to three sentences and must include the word on his slip of paper. The next student goes on.

Variations Each student is also given à number. The numbers determine the sequence in which the students have to contribute tî the story.

Remarks One can direct the contents of the story to à certain degree by the choice of words.

Newspaper report[22]

Aims Skills — writing

Language — reporting events, past tenses, passive

Other — imagination

Level Intermediate