Навигация

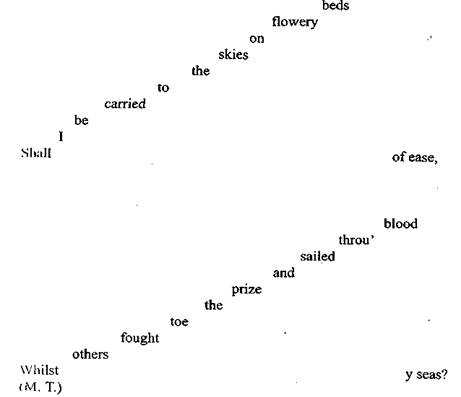

Discuss the poet-his life, philosophy, other poems he has written, and additional information that would interest your students

8. Discuss the poet-his life, philosophy, other poems he has written, and additional information that would interest your students.

9. Delineate the cultural elements appearing in the poem. Have the students compare these with elements in their own culture.

10. Help the students memorize the poem if they are interested in doing so. Poems learned by heart can be repeated by the group as a whole or by individual students and are apt to be even more attractive with familiarity. Besides, a poem which is memorized becomes the students' actual ""possession," a living part of his own linguistic and intellectual heritage.

Professor Gram told his students, "There's no better way to get familiar and at home with English than to have a few English poems running through your head." You may make the same observation with your students.

Games as a way at breaking the routine of classroom drill

Language games can add fun and variety to conversation sessions if the participants are fond of games. I, myself, have always enjoyed games, and students (most of them adults) seem to share my enthusiasm. Games are especially refreshing after demanding conversational activities such as debates or speeches. Here, the change of pace from the serious to the lighthearted is particularly welcome, although language games can fit into any directed conversation program quite well.

Socio-drama is an activity which obliges students to attend to the verbal environment. First, it is relevant to the students' interests, utilizing both extrinsic motivation, which refers to the students' daily interests and cares, and intrinsic motivation, which refers to the students' internal feelings and attitudes. . . . Furthermore, socio-drama is a problem-solving activity which stimulates real life situations and requires active student involvement.

Some teachers feel that language games are more appropriate in the manipulative phase than in the communicative phase of language learning. Most teachers, however, find language games valuable in both phases. In the manipulative phase, a game is a wonderful way to break the routine of classroom drill by providing relaxation while' remaining within the framework of language learning. In the communicative phase, a game can be stimulating and entertaining, and when the participants have stopped playing the game you can use it as a stimulus for additional conversation. For instance, if the group has just finished the game in which players indicate whether a statement is true or false by running to chairs labeled “True” and “False,” you may then ask questions about what happened during the game. ("Who was the first player?", "Who knocked the chair over by accident?", "What was the first true statement in the game?", "How many points did Team II score?" etc.)

Of course, for maximum benefit from a language game in either phase, the teacher should select only the best from the hundreds of language games available. Most people would agree that a good language game

(1) requires little or no advance preparation,

(2) is easy to play and yet provides the student with an intellectual challenge,

(3;) is short enough to occupy a convenient space in the conversation program,

(4) entertains the students but does not cause the group to get out of control, and

(5) requires no time-consuming correction of written responses afterward.

These games are for teen-agers and adults but often enjoyed by children as well, are especially suitable for use in conversation sessions. Before you read the instructions, you may wish to consider the following suggestions—suggestions designed to insure the greatest success with any of the games you select:

1. Make thorough preparations for the game. Read the rules to yourself several times so that you have a good understanding of how it is played. Gather materials for the games that require special equipment. Plan how you will direct conversation during or following the game.

2. Before introducing a game to a class, ask the students if they think they would enjoy this kind of activity. Occasionally an adult class expresses in no uncertain terms its lack of interest in the prospect of playing a game. When this happens, it is best to abandon the idea-at least for the time being.

3. Choose a game that allows as many students as possible to participate. If the class is large, a number of students will sit as the audience during some games. But even there, members of the audience may keep score and in other ways take part in the game. In small classes, you should make sure that every student has an active role in every game.

4. Be sure that the game you select is within the range of your students’ ability. Remember that the students will be greatly challenged by the fact that they are playing the game in a language other than their own.

5. Do not play a game at the beginning of the conversation period. Save the game for use in the middle or toward the end of the session, when the students would welcome a change of pace.

6. Give the directions to the game very clearly; making sure that everyone understands exactly how to play. You may want to play a few "trial" games first, just to make sure that everyone knows his role.

7. Direct the game yourself. Always stand in front of the class, so that all students can see you while you act as the leader or referee.

8. Be sure to follow the rules of the game exactly. If you do not "stick to the rules" but permit even one student to break a rule, you will establish a precedent that may lead to hostility among the students. It is always best, therefore, to anticipate problems of this kind and to play strictly according to the rules.

9. Keep the game well under control. Even though you want your students to have a good time, you cannot allow class discipline to disintegrate. Establish a pleasant but firm tone, and the students will be able to enjoy the game and learn in the process.

10. Observe how the individual players react to the game. Students who make an error in a game may feel a bit sensitive, so you should soften any blows to pride. If you constantly encourage a good spirit of fun, you will reduce the chances of unhappiness during the game.

11. In team games, try to have in each team an equal number of more proficient students and less proficient students. This will balance the teams and prevent embarrassment on the part of the weaker students. It also makes the contest more exciting. Some methodologists recommend that you set up permanent teams so that you do not have to name new teams each time. This has its merits, but you may prefer to create new teams each time you play a game, thus lending variety and interest to every fresh contest.

12. If a game does not seem to be going well, try a different game. Since some games appeal to one group of students but not to another, you should be flexible in your use of games.

13. Always stop playing a game before the students are ready to quit. In other words, never play a game so long that it begins to bore the participants. Similarly, do not play one game too often, since this will cause it to lose its novelty.

As you read the directions to the games that follow, do not be discouraged by the length of some of the directions. Long directions might make you think that the game is a complicated one, but all the games are easy for the student to learn if they are geared to his English proficiency level.

For this lively game you should set two chairs close to each other in front of the class and label one chair "True" and the other chair "False." Then divide the students into two teams of equal size and have members stand one behind the other on opposite sides of the room, with everyone facing the two chairs.

Explain that you are going to make a statement which may or may not be true, such as "John is absent today" (when he actually is absent) or "It was cloudy this morning'" (when it was sunny) or "Mary is wearing a red dress"' (when she is wearing a blue one) or "There are ten girls in this room" (when there are only seven). You should say the statement fairly rapidly, and only once.

As soon as you have completed the statement, a member of Team I and a member of Team II standing at the head of their respective team lines should quickly decide if the statement is true or false and run to the appropriate chair. The first person who sits down squarely on the right chair scores a point for his team. Both contestants then go to the end of their team lines and you make another statement for the second set of contestants. The game continues in this fashion until everyone has had a chance to play or until the time limit, agreed upon in advance, has been reached. Because the statements can be short and easy, or long and difficult, the game is ideal for all language-learning levels.

Classroom twenty questions

This is an excellent guessing game in which one person chooses a visible object in the room and the other students try to guess what it is by asking questions.

Suppose that you, for instance, begin the game by mentally selecting a pink scarf that one of the girl students is wearing. Tell the students that you have chosen an object and that each student can ask one question about it. You will give a complete answer to the question.

After several questions have been asked, the person whose turn is next may think he knows what the object is, In this case, he can ask, "Is it a (the). . . ? If he has guessed correctly, he wins the game and becomes the person who chooses the object in the second game. You will need someone to keep count of the number of questions asked. If no one has guessed the object after twenty questions, the person who selected the object wins the game and can choose another object for the second game.

The game might go something like this:

Student A: Is it as large as the map on the wall?

Answer: No, it isn't as large as the map.

Student B: Is it made of metal оm cloth?

Answer: It's made of cloth.

Student C: Does it belong to a student?

Answer: Yes, it belongs to a student.

Student D: Is it in front of me or behind me?

Answer: It's in front of you.

Student E: Is it round?

Answer: No, it isn't round.

Student F: Is it very expensive?

Answer: No, it isn't very expensive.

Student G: What color is it?

Answer: It's pink.

Student H: Is it Anna’s scarf?

Answer: Yes, it is. You've won the game!

At this point, Student H comes to the front of the room and mentally selects a new visible object for the next game.

If your students are quite advanced, you may wish to play the original game of 'Twenty Questions." In this form of the game, only questions that take a Yes or No answer are permitted. Another variation of the game is to select a famous person, living or dead, to be guessed, instead of an object.

What would you do if…?

This is such an amusing game that your class will probably want to play it often.

Begin the game by dividing the class into two teams of equal number. Designate one as Team I and the other as Team II. Then, write the following on the blackboard:

Team I Team II

What would you do if. . .? I would. . .

Now give everyone on Team I a slip of paper and explain that each person on the team must write an imaginative question beginning with What would you do if, . . . For example, someone might write: "What would you do if you saw a tiger in the street?" Someone else might write: "What would you do if you won a car in a lottery?". Etc.

As Team I carries out these directions, give everyone on Team II a piece of paper. Explain that each member of this team must write an imaginative sentence beginning / would. , . , For instance, someone could write "I would dance for hours." Another person might write "I would buy a wig.” etc.

When everyone has finished writing his assigned sentences, collect all Team I's questions in one box and all Team II's answers in another. You can now draw and read first a question and then an answer. This game is sometimes called "Cross Questions and Crooked Answers"; the fun comes from the fact that the questions and answers are so utterly and ridiculously unrelated.

Projects

Projects involving hobbies, crafts, physical exercise, sports, and civic services are extremely fruitful for English conversation groups, provided that only English is spoken during a given activity. All you need to do is to find a common denominator in your group's interests and your abilities to supervise plus adequate time, space, and equipment to create projects successful in their own right as well as in conversation practice. While possibilities for projects are almost limitless, here are a few that you may wish to consider for teen-age and adult groups:

1. Playing card games such as bridge, or board games like chess or Scrabble.

2. Engaging in carpentry.

3. Doing metal or leather work.

4. Making jewelry.

5. Exchanging recipes and demonstrating the preparation of certain dishes.

6. Sewing.

7. Telephoning English-speaking convalescents or shut-ins to brighten their day and to practice English over the telephone.

8. Participating in projects to improve the environment such as clearing a stream of rubbish.

9. Drawing or painting pictures to be used as decorations in the classroom or clubhouse.

10. Taking care of a bulletin board by bringing in and posting appropriate items for display.

11. Playing team sports such as volleyball or basketball.

12. Learning songs and dances that are popular in English-speaking countries.

13. Giving talent shows, plays, or concerts.

14. Participating in various audio-motor units. An audio-motor unit is a language teaching device developed by Robert Elkins, Theodore Kalivoda, and Genelle Morain in which the teacher records a sequence of ten to twenty commands around a common theme on tape. When the teacher plays the tape, he pantomimes responses to the commands while the students watch. Next, the students join the teacher in pantomiming responses to the tape. Eventually, the teacher can read off commands in a scrambled fashion with the students performing the correct physical response to each command. For example, if the teacher has recorded a series of commands about unwrapping a birthday present, the following audio-motor unit might result:

(1) Pick up the package.

(2) Shake it gently to see if it rattles.

(3) Put the box down.

(4) Remove the card.

(5) Read the card.

(6) Put the card down.

(7) Untie the ribbon.

(8) Remove the paper.

(9) Open the box.

(10) Look surprised as you see a sweater inside the box.

(11) Take the sweater out of the box.

(12) Try the sweater on.

(13) Look at yourself in the mirror.

(14) Take the sweater off.

(15) Lay the sweater on the table.

(16) Fold the paper up neatly.

(17) Put the paper and ribbon in a drawer.

(18) Hang the sweater in the closet.

Since this sequence represents a typical birthday ritual in an English-speaking country, it contains elements that may contrast with birthday customs in the students' country. After the group has completed the pantomime, the teacher might want to lead a discussion on such matters as birthday cards, gift wrapping, and birthday celebrations in general.

A project that provides abundant material for conversation is an imaginary trip to a real town in an English-speaking country. You can select from a map of the United States, for instance, a medium-sized town in a section of the country that interests your class. Your students may then write a letter to the Chamber of Commerce in the town, explaining their interest in the community and asking for pertinent information. This might include brochures describing the town, postcards, a street map, telephone book, parking ticket, restaurant menus, local newspapers, and the like. If the Chamber of Commerce cannot answer the request directly, they may put your students in touch with local schools or service clubs that might be willing to send these items. When the material is received, you and your students can inspect and discuss the various items at length.

A lasting relationship between citizens of the two towns may sometimes result from such a project. In an article entitled "Teaching the Telephone Book," Clifford Harrington describes his Japanese students' experience with a "city-to-city" project: "One unexpected benefit was brought about by an article concerning our class that appeared in an issue of the local newspaper we were studying. A young American who was planning to vacation in Japan and whose family had lived in our' town since 1885 learned about us through this article. His visit to our class when he arrived in Tokyo was one of the highlights of the course. Perhaps the most rewarding result was the fact that one young Japanese woman who was planning to take a trip to the United States after completing her studies decided to visit the community we had studied. She now knew so much about it that she wanted to see with her own eyes the places she had visited in her imagination."

Content-based instruction (CBI)

In recent years, increasing numbers of language educators have turned to content-based instruction and project work to promote meaningful student engagement with language and content learning. Through content-based instruction, learners develop language skills while simultaneously becoming more knowledgeable citizens of the world. By integrating project work into content-based classrooms, educators create vibrant learning environments that require active student involvement, stimulate higher level thinking skills, and give students responsibility for their own learning. When incorporating project work into content-based classrooms, instructors distance themselves from teacher-dominated instruction and move towards creating a student community of inquiry involving authentic communication, cooperative learning, collaboration, and problem-solving.

In this article, I shall provide a rationale for content-based instruction and demonstrate how project work can be integrated into content-based classrooms. I will then outline the primary characteristics of project work, introduce project work in its various configurations, and present practical guidelines for sequencing and developing a project. It is my hope that language teachers and teacher educators will be able to adapt the ideas presented here to enhance their classroom instruction.

Content-based instruction (CBI) has been used in a variety of language learning contexts for the last 25 years, though its popularity and wider applicability have increased dramatically in the past 10 years. There are numerous practical features of CBI which make it an appealing approach to language instruction:

In a content-based approach, the activities of the language class are specific to the subject matter being taught, and are geared to stimulate students to think and learn through the use of the target language. Such an approach lends itself quite naturally to the integrated teaching of the four traditional language skills.

For example, it employs authentic reading materials which require students not only to understand information but to interpret and evaluate it as well. It provides a forum in which students can respond orally to reading and lecture materials. It recognizes that academic writing follows from listening and reading, and thus requires students to synthesize facts and ideas from multiple sources as preparation for writing. In this approach, students are exposed to study skills and learn a variety of language skills which prepare them for the range of academic tasks they will encounter (Brinton, Snow, and Wesche 1989:2)[23]

This quotation reflects a consistent set of descriptions by CBI practitioners who have come to appreciate the many ways that CBI offers ideal conditions for language learning. Research in second language acquisition offers additional support for CBI; yet some of the most persuasive evidence stems from research in educational and cognitive psychology, even though it is somewhat removed from language learning contexts. Worth noting here are four findings from research in educational and cognitive psychology that emphasize the benefits of content-based instruction:

1. Thematically organized materials, typical of content-based classrooms, are easier to remember and learn (Singer 1990)[24].

2. The presentation of coherent and meaningful information, characteristic of well-organized content-based curricula, leads to deeper processing and better learning (Anderson 1990)[25].

3. There is a relationship between student motivation and student interest—common outcomes of content-based classes—and a student's ability to process challenging materials, recall information, and elaborate (Alexander, Kulikowich, and Jetton 1994)[26].

4. Expertise in a topic develops when learners reinvest their knowledge in a sequence of progressively more complex tasks (Bereiter and Scardamalia 1993)[27], feasible in content-based classrooms and usually absent from more traditional language classrooms because of the narrow focus on language rules or limited time on superficially developed and disparate topics (e.g., a curriculum based on a short reading passage on the skyscrapers of New York, followed by a passage on the history of bubble gum, later followed by an essay on the volcanos of the American Northwest).

These empirical research findings, when combined with the practical advantages of integrating content and language learning, provide persuasive arguments in favor of content-based instruction. Language educators who adopt a content-based orientation will find that CBI also allows for the incorporation of explicit language instruction (covering, for example, grammar, conversational gambits, functions, notions, and skills), thereby satisfying students' language and content learning needs in context (see Grabe and Stoller[28] 1997 for a more developed rationale for CBI.)

Content-based instruction allows for the natural integration of sound language teaching practices such as alternative means of assessment, apprenticeship learning, cooperative learning, integrated-skills instruction, project work, scaffolding, strategy training, and the use of graphic organizers. Although each of these teaching practices, is worthy of extended discussion, wewill focus solely on project work and its role in content-based instructional formats.

Some language professionals equate project work with in-class group work, cooperative learning, or more elaborate task-based activities. The purpose is to illustrate how project work represents much more than group work per se. Project-based learning should be viewed as a versatile vehicle for fully integrated language and content learning,- making it a viable option for language educators working in a variety of instructional settings including general English, English for academic purposes (EAP), English for specific purposes (ESP), and English for occupational/vocational/professional purposes, in addition to pre-service and in-service teacher training. Project work is viewed by most of its advocates "not as a replacement for other teaching methods" but rather as "an approach to learning which complements mainstream methods and which can be used with almost all levels, ages and abilities of students" (Haines 1989:1).

In classrooms where a commitment has been made to content learning as well as language learning (i.e., content-based classrooms), project work is particularly effective because it represents a natural extension of what is already taking place in class. So, for example, in an EAP class structured around environmental topics, a project which involves the development of poster displays suggesting ways in which the students' school might engage in more environmentally sound practices would be a natural outcome of the content and language learning activities taking place in class. In a vocational English course focusing on tourism, the development of a promotional brochure highlighting points of interest in the students' home town would be a natural outgrowth of the curriculum. In a general English course focusing on cities in English-speaking countries, students could create public bulletin board displays with pictorial and written information on targeted cities. In an ESP course on international law, a written report comparing and contrasting the American legal system and the students' home country legal system represents a meaningful project that allows for the synthesis, analysis, and evaluation of course content. Project work is equally effective in teacher training courses. Thus, in a course on materials development, a student-generated handbook comprising generic exercises for language skills practice at different levels of English proficiency represents a useful and practical project that can be used later as a teacher-reference tool. The hands-on experience that the teachers-in-training have with project-based learning could, in turn, transfer to their own lesson planning in the future These examples represent only some of the possibilities available to teachers and students when incorporating project work into content-based curricula.

Project work has been described by a number of language educators, including Carter and Thomas (1986), Ferragatti and Carminati (1984), Fried-Booth (1982, 1986), Haines (1989), Legutke (1984, 1985), Legutke and Thiel (1983), Papandreou (1994), Sheppard and Stoller (1995), and Ward (1988). Although each of these educators has approached project work from a different perspective, project work, in its various configurations, shares these features:

1. Project work focuses on content learning rather than on specific language targets. Real-world subject matter and topics of interest to students can become central to projects.

2. Project work is student centered, though the teacher plays a major role in offering support and guidance throughout the process.

3. Project work is cooperative rather than competitive. Students can work on their own, in small groups, or as a class to complete a project, sharing resources, ideas, and expertise along the way.

4. Project work leads to the authentic integration of skills and processing of information from varied sources, mirroring real-life tasks.

5. Project work culminates in an end product (e.g., an oral presentation, a poster session, a bulletin board display, a report, or a stage performance) that can be shared with others, giving the project a real purpose. The value of the project, however, lies not just in the final product but in the process of working towards the end point. Thus, project work has both a process and product orientation, and provides students with opportunities to focus on fluency and accuracy at different project-work stages.

6. Project work is potentially motivating, stimulating, empowering, and challenging. It usually results in building student confidence, self-esteem, and autonomy as well as improving students' language skills, content learning, and cognitive abilities.

Though similar in many ways, project work can take on diverse configurations. The most suitable format for a given context depends on a variety of factors including curricular objectives, course expectations, students' proficiency levels, student interests, time constraints, and availability of materials. A review of different types of projects will demonstrate the scope, versatility, and adaptability of project work.

Projects differ in the degree to which the teacher and students decide on the nature and sequencing of project-related activities, as demonstrated by three types of projects proposed by Henry[29] (1994): Structured projects are determined, specified, and organized by the teacher in terms of topic, materials, methodology, and presentation; unstructured projects are defined largely by students themselves; and semi-structured projects are defined and organized in part by the teacher and in part by students.

Projects can be linked to real-world concerns (e.g., when Italian ESP students designed a leaflet for foreign travel agencies outside of Europe describing the advantages of the European Community's standardization of electrical systems as a step towards European unity.

This ESP project, titled "Connecting Europe with a New Plug," was designed by Italian instructors Laura Chiozzotto, Innocenza Giannasi, Laura Paperini, and Antonio Ragosa for students of electrotechnics and electronics.

Projects can also be linked to simulated real-world issues when EAP students staged a debate on the pros and cons of censorship as part of a content-based unit on censorship. Projects can also be tied to student interests, with or without real-world significance when general English students planned an elaborate field trip to an international airport where they conducted extensive interviews and videotaping of international travelers.

Projects can also differ in data collection techniques and sources of information as demonstrated by these project types. Research projects necessitate the gathering of information through library research. Similarly, text projects involve encounters with "texts" (e.g., literature, reports, news media, video and audio material, or computer-based information) rather than people. Correspondence projects require communication with individuals (or businesses, governmental agencies, schools, or chambers of commerce) to solicit information by means of letters, faxes, phone calls, or electronic mail. Survey projects entail creating a survey instrument and then collecting and analyzing data from "informants." Encounter projects result in face-to-face contact with guest speakers or individuals outside the classroom Projects may also differ in the ways that information is "reported" as part of a culminating activity. Production projects involve the creation of bulletin board displays, videos, radio programs, poster sessions, written reports, photo essays, letters, handbooks, brochures, banquet menus, travel itineraries, and so forth.

Whatever the configuration, projects can be carried out intensively over a short period of time or extended over a few weeks, or a full semester; they can be completed by students individually, in small groups, or as a class; and they can take place entirely within the confines of the classroom or can extend beyond the walls of the classroom into the community or with others via different forms of correspondence.

Project work, whether it is integrated into a content-based thematic unit or introduced as a special sequence of activities in a more traditional classroom, requires multiple stages of development to succeed. Fried-Booth (1986)[30] proposes an easy-to-follow multiple-step process that can guide teachers in developing and sequencing project work for their classrooms. Similarly, Haines (1989) presents a straightforward and useful description of project work and the steps needed for successful implementation. Both the Fried-Booth and Haines volumes include detailed descriptions of projects that can be adapted for many language classroom settings. They also offer suggestions for introducing students to the idea of student-centered activity through bridging strategies (Fried-Booth 1986)2 and lead-in activities (Haines 1989), particularly useful if one's students are unfamiliar with project work and its emphasis on student initiative and autonomy.

The new 10-step sequence (see Figure 1) is described here in detail. The revised model gives easy-to-man-age structure to project work and guides teachers and students in developing meaningful projects that facilitate content learning and provide opportunities for explicit language instruction at critical moments in the project. These language "intervention" lessons will help students complete their projects successfully and will be appreciated by students because of their immediate applicability and relevance. The language intervention steps (IV, VI, and VIII) are optional in teacher education courses, depending on the language proficiency and needs of the teachers-in-training.

Developing a Project in a Language Classroom

Step I: Agree on a theme for the project

Step II: Determine the final outcome

Step III: Structure the project

Step IV:

Prepare students for

the language demands

of Step V

Step V:

Gather information

Step VI:

Prepare students for

the language demands

of Step VII

Step VII:

Compile and analyze information

Step VIII:

Prepare students for

the language demands

of Step IX

Step IX: Present final product

Step X: Evaluate the prodject.

To understand the function of each proposed step, imagine a content-based EAP classroom focusing on American elections.(A parallel discussion could be developed for classrooms—general English, EAP, ESP, vocational English, and so forth—focusing on American institutions, demography, energy alternatives, farming safety, fashion design, health, the ideal automobile, insects, Native Americans, pollution, rain forests, the solar system, etc.). The thematic unit is structured so that the instructor and students can explore various topics: the branches of the U.S. government, the election process, political parties with their corresponding ideologies and platforms, and voting behaviors. Information on these topics is introduced by means of readings from books, newspapers, and news magazines; graphs and charts; videos; dicto-comps; teacher-generated lectures and note-taking activities; formal and informal class discussions and group work; guest speakers; and U.S. political party promotional materials. While exploring these topics and developing some level of expertise about American elections, students improve their listening and note-taking skills, reading proficiency, accuracy and fluency in speaking, writing abilities, study skills, and critical thinking skills. To frame this discussion, it should be noted that the thematic unit is embedded into an integrated-skills, content-based course with the following objectives:

1. To encourage students to use language to learn something new about topics of interest

2. To prepare students to learn subject matter through English

3. To expose students to content from a variety of informational sources to help stu dents improve their academic language and study skills

4. To provide students with contextualized resources for understanding language and content

5. To simulate the rigors of academic courses in a sheltered environment

6. To promote students' self-reliance and engagement with learning

After being introduced to the theme unit and its most fundamental vocabulary and concepts, the instructor introduces a semi-structured project to the class that will be woven into class lessons and that will span the length of the thematic unit. The teacher has already made some decisions about the project: Students will stage a simulated political debate that addresses contemporary political and social issues. To stimulate interest and a sense of ownership in the process, the instructor will work with the students to decide on the issues to be debated, the number and types of political parties represented in the debate, the format of the debate, and a means for judging the debate. To move from the initial conception of the project to the actual debate, the instructor and students follow 10 steps.

Step I: Students and instructor agree on a theme for the project

To set the stage, the instructor gives students an opportunity to shape the project and develop some sense of shared perspective and commitment. Even if the teacher has decided to pursue a structured project, for which most decisions are made by the instructor, students can be encouraged to fine-tune the project theme. While shaping the project together, students often find it useful to make reference to previous readings, videos, discussions, and classroom activities. During the initial stage of the American elections project, students brainstormed issues that might be featured in an American political debate. Through discussion and negotiation, students identified the following issues for consideration: taxes, crime, welfare, gun control, abortion, family leave, foreign policy, affirmative action, election reform, immigration, censorship, the environment, and environmental legislation. By pooling resources, information, ideas, and relevant experiences, students narrowed the scope of the debate by choosing select issues from within the larger set of brainstormed issues that were of special interest to the class and that were "researchable," meaning that resources were available or accessible for student research.

Step II: Students and instructor determine the final outcome whereas the first stage of project work involves establishing a starting point, the second step entails defining an end point, or the final outcome. Students and instructor consider the nature of the project, its objectives, and the most appropriate means to culminate the project. They can choose from a variety of options including a written report, letter, poster or bulletin board display, debate, oral presentation, information packet, handbook, scrapbook, brochure, newspaper, or video. In the case of the American elections project, the teacher had already decided that the final outcome would be a public debate between two fictitious political parties. In this second stage of the project, students took part in defining the nature and format of the debate and designating the intended audience. With the help of the instructor, it was decided that the class would divide itself into five topical teams, each one responsible for debating one of the issues previously identified; topical teams would generate debatable propositions on their designated issue and then divide into two subgroups so that each side of the issue could be represented in the debate. Students would also be grouped into two political parties, which they would name themselves, with one side of each issue represented in the political party; the issues and corresponding perspectives would form the party platform.

The class decided to invite English-speaking friends and graduate students enrolled in a TESL/TEFL program to serve as their audience and judges. It was decided that the audience would vote on which team presented the most persuasive arguments during the debate.

Step III: Students and instructor structure the project.

After students have determined the starting and end points of the project, they need to structure the "body" of the project. Questions that students should consider are as follows: What information is needed to complete the project? How can that information be obtained (e.g., a library search, interviews, letters, faxes, e-mail, the World Wide Web, field trips, viewing of videos)? How will the information, once gathered, be compiled and analyzed? What role does each student play in the evolution of the project (i.e., Who does what?)? What time line will students follow to get from the starting point to the end point? The answers to many of these questions depend on the location of the language program and the types of information that are within easy reach (perhaps collected beforehand by the instructor) and those that must be solicited by "snail" mail, electronic mail, fax, or phone call. In this American elections project, it was decided that topical team members would work together to gather information that could be used by supporters and opponents of their proposition before actually taking sides. In this way, topical team members would share all their resources, later using it to take a stand and plan a rebuttal. Rather than keeping information secret, as might be done in a real debate setting, the idea was to establish a cooperative and collaborative working atmosphere. Topical team members would work as a group to compile gathered information (in the form of facts, opinions, and statistics) and then analyze it to determine what was most suitable to the sides supporting and opposing their proposition. At this point, students would subdivide into groups of supporters and opponents and then work separately (and with other party members) to prepare for the debate. At that time, students would decide on different roles: the spokespersons, the "artists" who would create visuals (charts and graphs) to be used during the debate, and so forth.

Step IV: Instructor prepares students for the language demands of information gathering

It is at this point that the instructor determines, perhaps in consultation with the students, the language demands of the information gathering stage (Step V). The instructor can then plan language instruction activities to prepare students for information gathering tasks. If, for example, students are going to collect information by means of interviews, the instructor might plan exercises on question formation, introduce conversational gambits, and set aside time for role-plays to provide feedback on pronunciation and to allow students to practice listening and note-taking or audio-taping. If, on the other hand, students are going to use a library to gather materials, the instructor might review steps for finding resources and practice skimming and note-taking with sample texts. The teacher may also help students devise a grid for organized data collection. If students will be writing letters to solicit information for their project, the teacher can introduce or review letter formatting conventions and audience considerations, including levels of formality and word choice. If students will be using the World Wide Web for information gathering, the instructor can review the efficient use of this technology.

Step V: Students gather information

Students, having practiced the language, skills, and strategies needed to gather information, are now ready to collect information and organize it so that others on their team can make sense of it. In the project highlighted here, students reread course readings in search for relevant materials, used the library to look for new support, wrote letters to political parties to determine their stand on the issue under consideration, looked into finding organizations supporting or opposing some aspect of their proposition (e.g., gun control groups) and solicited information that could possibly be used in the debate. During this data-gathering stage, the instructor, knowing the issues and propositions being researched, also brought in information that was potentially relevant, in the form of readings, videos, dicto-comps, and teacher-generated lectures, for student consideration.

Step VI: Instructor prepares students for the language demands of compiling and analyzing data

After successfully gathering information, students are then confronted with the challenges of organizing and synthesizing information that may have been collected from different sources and by different individuals.

The instructor can prepare students for the demands of the compilation and analysis stage by setting up sessions in which students organize sets of materials, and then evaluate, analyze, and interpret them with an eye towards determining which are most appropriate for the supporters and opponents of a given proposition. Introducing students to graphic representations (e.g., grids and charts) that might highlight relationships among ideas is particularly useful at this point.

Step VII: Students compile and analyze information

With the assistance of a variety of organizational techniques (including graphic organizers), students compile and analyze information to identify data that are particularly relevant to the project. Student teams weigh the value of the collected data, discarding some, because of their inappropriacy for the project, and keeping the rest. Students determine which information represents primary "evidence" for the supporters and opponents of their proposition. It is at this point that topical teams divide themselves into two groups and begin to work separately to build the strongest case for the debate.

Step VIII: Instructor prepares students for the language demands of the culminating activity

At this point in the development of the project, instructors can bring in language improvement activities to help students succeed with the presentation of their final products. This might entail practicing oral presentation skills and receiving feedback on voice projection, pronunciation, organization of ideas, and eye contact. It may involve editing and revising written reports, letters, or bulletin board display text. In the case of the American elections debate project, the instructor focused on conversational gambits to be used during the debate to indicate polite disagreement and to offer divergent perspectives (see Mach, Stoller, and Tardy 1997)[31]. Students practiced their oral presentations and tried to hypothesize the questions that they would be asked by opponents. They timed each other and gave each other feedback on content, word choice, persuasiveness, and intonation. Students also worked with the "artists" in their groups to finalize visual displays, to make sure they were grammatically correct and easily interpretable by the audience. Students also created a flyer announcing the debate (see appendix), which served as an invitation to and reminder for audience members.

Step IX: Students present final product

Students are now ready to present the final outcome of their projects. In the American elections project, students staged their debate in front of an audience, following the format previously agreed upon. The audience voted on the persuasiveness of each political party, and a winner was declared. In the case described here, the debate was videotaped so that students could later review their debate performances and receive feedback from the instructor and their peers.

Step X: Students evaluate the project

Although students and instructors, alike, often view the presentation of the final product as the very last stage in the project work process, it is worthwhile to ask students to reflect on the experience as the last and final step. Students can reflect on the language that they mastered to complete the project, the content that they learned about the targeted theme (in the case highlighted here that would be American elections, party platforms, and the role of debate in the election process), the steps that they followed to complete the project, and the effectiveness of their final product. Students can be asked how they might proceed differently the next time or what suggestions they have for future project work endeavors. Through these reflective activities, students realize how much they have learned and the teacher benefits from students' insights for future classroom projects.

Content-based instruction and project work provide two means for making English language classrooms more vibrant environments for learning and collaboration. Project work, however, need not be limited to content-based language classes. Language teachers in more traditional classrooms can diversify instruction with an occasional project. Similarly, teacher educators can integrate projects into their courses to reinforce important pedagogical issues and provide trainees with hands-on experience, a process that may be integrated into future classrooms of their own.

Whether a project centers around American elections, demography, peace their high school results (matriculation).

Conclusion:

Some Practical Techniques for Language Teaching

The English Teacher Working with Groups Groups have to have adequate time to prepare to succeed. This time includes time for all to study the material and time for a modeling activity by the teacher. Then the teacher should give a grade to the group and to the individual. Otherwise the A' students carry the work load to keep their semester grades up and everyone gets an equal grade.

Groups are chosen by a variety of methods. The most common methods are to either let students choose their own groups or to group them according to ability. Allowing students to choose their own groups may result in some people being left out and those who don't relate well to any group being left to work together. Grouping by ability so that there are some capable students in each group usually works well. If you choose the groups, you may unknowing place those students with past relationship problems together. You may then expect them to learn to work together, but be aware that you may not be able to leave the room with such groupings, or even put your attention somewhere else. You may also select the groups by drawing names, numbers, etc. Most students accept the fairness of a random selection, especially if a student draws the choices, but dysfunctional groups may result. In my experience, I wait until I know the class and the individual students before I begin group work and then I select the groups. And I keep a record of the groups and which groupings were most successful. However groups are chosen, don't allow members of one group to talk to members of another group or your group dynamics will be considerably less effective.

Groups where students each do work in their established skill areas may accomplish a good project, may demonstrate good collaborative skills, may gain recognition for the students, but may not accomplish much growth in students' abilities. A class which is totally project oriented may result in a student spending a semester without broadening academic or other desirable skills. An art student may only draw, a music student may only supply the sound, etc.

If the entire class can not work profitably doing group work, then cease that activity. If only one or two groups are not working profitably, then decide whether the other groups are benefitting enough to have the two unproductive groups continue in their actions.

The English Teacher Designing Lessons and Units In developing a class, interlock lessons and units to build and develop skills and to maintain skills and knowledge. Don't teach something that you drop and never teach any part of again.... or never use the knowledge of any part again. If you do totally drop material, you are teaching the student to forget and/or are confirming the concept that it is ok to forget -and/or- that what you are teaching is not important enough to remember.

When you design a lesson, it usually takes two or three times presenting it to a class to work out all the problems. [In my first Methods class we were asked to design a poetry lesson for 11th graders without any prior class instruction in how to accomplish this. Then all the faults of our presentations were pointed out. It was a potentially discouraging experience... leaving the class with the impression that new lessons had to be perfect, without flaws. In the real world, a perfect first lesson rarely happens.] Don't give up the idea of creating some lessons of your own and instead rely solely on 'canned' lessons because of one or two imperfect first results.

It can take two or three years to develop a class. The first time you give a test, if you designed the test, it is the test that is being tested. If it is a test someone else designed, then the first time that you give it, your teaching is being tested. The Teaching Literature page has examples of some test designs as does Teaching Media.

The English Teacher Using Transition Time Activities Transition activities are "halfway" activities to help students make the transition from whatever is distracting them from learning at the beginning of class to full attention on the day's lesson. In our school 9th graders do daily reading. 10th graders do basic writing forms and 11th graders do advanced writing forms for the average 9th grade class it is easier to start a lesson if the class has already made a partial transition. For college preparation level classes this activity may not be as productive, since they may be able to get to work right away, and are already reading regularly. To begin daily reading, have a box that they can put their reading books into so that when they come to class the next day [or when you announce reading time] they can get their books.

When you begin this activity, have the first student in each row get a book [from an assortment of paperbacks that you get from your librarian] for each person in their row. The student lets the 2nd student in the row have first choice; the third student has the next choice, and so forth until all have chosen. The student who selected all the books for the row gets the book that is left after the others have chosen. No one complains, because the first student after all had the total choice and the students in the row won't complain about another student's selections, particularly if that student has the book remaining after every one else has chosen. [NOTE: If you as a teacher tell the class to "get a book" from the book rack, then you will have a lot of talking, complaining about there being no interesting books, etc. Plus there will be conversations around the books, and return trips for students that may never be satisfied with their choices.] They have to read that book until the end of the first reading time.

At the end of the first reading time, the student can either put the book into the box to reserve books for that class, or they can return it to the student who chose them. This procedure is repeated as many times as necessary, usually less than four to five days. By that time most will have books, or the few that don't can make their own choices. For the loud complainers over this system and the book choices available, simply tell them that they can bring their own books the next day, and then they can either bring them each day, or put them in that class's reading box with the others being read.

Later, when students get involved with their reading, they will read after tests and other activities when they finish before others. Then others follow their actions and you are not telling students to be quiet until the others finish their tests, etc.. This involvement with reading reduces your stress -and- the students' stress.

Language teaching is teaching language

Language is a system which needs to be understood and internalized. Language is a habit which requires repetition and intensive oral practice. Language is a set of conventions, customs which the students needs to learn as well as the structures. Language is a means of communication which is used to accomplish different tasks and purposes. Language is a means to an end and is not used for its own sake. Language is a natural activity, not an academic exercise.

Language is what, how and why

Knowing a language is muvh more than knowing the structure. Vocabulary and grammar is what is said. Prononciation, stress and intonation are how it is said.

Knowing the language is not eonugh

Classroom activities should be planned so that they have a real, natural communicative purpose. It is better to present the language in a text which is studied for a purpose other than language itself (reading a bus shedule to find out what a bus goes form one place to another). Students need to use languge for a real purpose.

Interesting communicative tasks increase motivation

Teachers need to give students tasks which develop the skills necessary to communicate in the new language. These tasks should be similar to things that native speakersw do with the language. Some examples: a) listening to public announcments (at an airport)

b) drawing a picture from spoken instructions;

c) describing what a person looks like

d) conducting interviews or questionaries

e) reading brochures, menus,or schedules

f) following written instructions;

g) writing a note to a classmate

Used literature:

1. Burt, M,K, and H. C. Dulay (eds.) (1975). New Directions in Second Language Learning, Teaching and Bilingual Education. Washington: TESOL.

2. Chamberlin, A. And A. Wright (1974). What Do You Think? London: Longman

3. Cole,P. (1970). “An adaption of group dynamic techniques to foreign language teaching.”TESOL Quaterly Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 353 – 360

4. Dobson, J.M. (1974). Effective Techniques for English Conversation Groups. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

5. Dubin, F and M. Margol (1977). It’s Time To Talk: Communication activities for learning English as a new language. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice – Hall.

6. Green K. (1975). “Values clarification theory in ESL and bilingual education.” TESOL Quaterly Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 155 – 164.

7. Herbert, D. and G. Sturtridge (1979). Simulations. ELT Guide 2. London: The British Council.

8. Heyworth, F. (1978). The Language of Discussion. Role-play exercises for advanced students. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

9. Johnson, K. and K. Morrow (eds.) (1981). Communication in the Classroom. London: Longman.

10. Jones, K. (1982). Simulations in Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

11. Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

12. Omaggio, A. (1976). “Real communication: Speaking a living language.” Foreign Language Annals Vol.9. No. 2, pp. 131 – 133.

13. Revell, J. (1979). Teacing Techniques for Communicative English. London: Macmillan.

14. Rogers, J. (1978). Group Activities for Language Learning. SEAMEO Regional Language Centre Occasional Papers, No. 4. Singapore: SEAMEO Regional Language Centre (MS)

15. Scarcella, R.C. (1978). “Socio-drama for social interaction.” TESOL Quarterly Vol.12 No. 1, pp. 41 – 46

16. Thomas, I. (1978). Communication Activities for Language Learning. Wellington: Victoria University, English Language Institute (MS).

17. Wright, A. D. Betteridge and M. Buckby (1979). Games for Language Learning. Cambridge University Press (2nd ed. 1984).

18. Zelson, N.J. (1974). “Skill using activities in the foreign language classroom.” Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 33 - 35

[1] Black C, and W. Butzkumm (1977) Praxis des neusprachlichen Unterrichts Vol. 24, #2, pp. 115-124

[2] Cole, P. (1970) “An adaption of group dynamic techniques to foreign language teaching” TESOL. Quality. Vol. 4. # 4, pp. 353 - 360

[3] Hutchinson, I., and A. Waters. 1987. English for specific purposes: a learning – centered approach. Hasgow^ Cambrige University Press

[4] Gagne . R. and L.J. Briggs.1988 Principles of Instructional design New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

[5] Dillingham, A.ME., N.T. Skaggs, and J.L. Carlson. 1992. Economics: Individual choice and its consequences. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

[6] Hamilton, R., and E. Ghatala. 1994. Learning and instruction. New York: Mc. Graw - Hill

[7] Oller, J.W. 1993. Methods that work. Boston, M.A: Heinle and Heinle

[8] Davis, E. , and H. Nur. 1994 Helping teachers and students understand learning styles. English Teaching Forum, 32, 3, pp. 12-19

[9] Brown G. and G Yule. 1983. Teaching the Spoken Language. Cambridge University press.

[10] Bereen, M. 1984 Processes in syllabus design, General English Sillabus Design. Oxford: Pergamon Press

[11] Littlewood W. 1981 communicative Language Teaching – an Introduction cambridge University Press

[12] http://www.htt.com/gamesin teaching

[13] Dubin, F and M. Margol (1977). It’s Time To Talk: Communication activities for learning English as a new language. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice – Hall.

[14] Aronson, E, N. Blaney, J. Sikes, G. Stephan and M. Snapp (1975) “The jigasw route to learning and liking” Pschology today Vol. 8 pp. 43 – 50

[15] Moskowitz, Y (1978) Caring and Sharing in the Foreign Language Class. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

[16] http:/www.htp.com/gamesinteaching

[17] Howe, L. W. and M.M Howe (1975) Personilizing Education. New York: Hart

[18] Simon S.B., L.W. Howe, and H. Krichenbaum (1972) Values Clarification. New York : Hart.

[19] Scarcella, R.C. (1978). “Socio-drama for social interaction.” TESOL Quarterly Vol.12 No. 1, pp. 41 – 46

[20] http://www.htt.com/poetry/in/teachingenglish

[21] http://www.htt.com/fun/tasks/in/taching

[22] http://www.htt.com/gamesinteaching

[23] Brinton D., M. Show and M. Welshe. 1989. Content based second language instruction. New York: Heinle and Heinle.

[24] Singer, M. (1990) Psychology of Language: An Introduction to Sentence and Discourse Processing. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum.

[25] Anderson, J. 1990 Cognitive psychology and its mplications. New York: W. H. Freeman

[26] Alexander,P., J. Kulikowich and T. Jetton (1994) The role of subject – matter knowledge and interest in the processing of linear and non linear texts. Review of educational Research, 64, 2, pp. 201-252

[27] Bereiter, C. and M. Scardamalia (1993) Surpassing purselves. Chicago. Open Court Press.

[28] Grabe, W. and F. Stoller 1997. Content-based instruction . New York: Addison Wesley London

[29] Henry. J. 1994 Teaching thruogh projects. London. Kogan Page Limited.

[30] Fried – Booth , D. 1982. Project work with advanced classes. ELT journal, 36, 2, pp. 98 - 103

[31] Mach, T. , F. Stoller, and C Tardy. 1997 A gambit – driven debate. In New Ways in Content-based Instruction pp. 64-68. Alexandra, VA.: TESOL.

Похожие работы

e. Journalists, financial markets and the public are still learning the new strategy and language of monetary policy in the euro area. By its nature, the challenge of improving communications between the Eurosystem and the public is two-sided. On the one hand, the ECB must use a clear and transparent language consistent with the strategy it has adopted. It must help the public understand the ...

... may allow workers to be flexible when the company needs to change or is having difficulties. · Workers identify with other employees. This may help with aspects of the business such as team work. · It increases the commitment of employees to the company. This may prevent problems such as high labour turnover or industrial relations problems . · It motivates workers in their jobs. ...

of promoting a morpheme is its repetition. Both root and affixational morphemes can be emphasized through repetition. Especially vividly it is observed in the repetition of affixational morphemes which normally carry the main weight of the structural and not of the denotational significance. When repeated, they come into the focus of attention and stress either their logical meaning (e.g. that of ...

... Intelligences, The American Prospect no.29 (November- December 1996): p. 69-75 68.Hoerr, Thomas R. How our school Applied Multiple Intelligences Theory. Educational Leadership, October, 1992, 67-768. 69.Smagorinsky, Peter. Expressions:Multiple Intelligences in the English Class. - Urbana. IL:National Council of teachers of English,1991. – 240 p. 70.Wahl, Mark. ...

0 комментариев