Навигация

3. The Composite Sentence

Composite sentences, as we know divide into compound and complex sentences. The difference between them is not only in the relations of coordination or subordination, as usually stated. It is also important to know what is coordinated or subordinated. In compound sentences the whole clauses are coordinated, together with their predications.

In complex sentences a clause is mostly subordinated not to the whole principal clause but to some word in it which may be regarded as its head-word. In I know where he lives the subordinate clause is an adjunct of the objective verb know. In I know the place where he lives the subordinate clause is the adjunct of the noun place. In The important thing is where he lives the subordinate clause is an adjunct of the link-verb is. The only exception is the subordinate clause in a sentence like Where he lives is unknown in which it functions as the subject.

These peculiarities of compound and complex sentences may account for the difference in their treatment. The clauses of compound sentences are often regarded as independent. Some linguists are even of the opinion that compound sentences are merely sequences of simple sentences, combinations of sentences. x The clauses of a complex sentence, on the contrary, are often treated as forming a unity, a simple sentence in which some part is replaced by a clause a. Such extreme views are, to our mind, not quite justified, especially if we take into consideration that the border lines between coordination (parataxis) and subordination (hypotaxis are fluid. A clause may be introduced by a typical subordinating conjunction and yet its connection with the principal clause is so loose that it can hardly be regarded as a subordinate clause at all.

Cf. I met John, who told me (= and he told me) the big news.

Or, conversely, a coordinating conjunction may express relations typical of subordination.

E.g. You must interfere now; for (cf. because) they are getting quite beyond me. (Shaw).

As already noted, the demarcation line between a compound sentence and a combination of sentences, as well as that between compound words and combinations of words, is somewhat vague. Yet, the' majority of compound words and compound sentences are established in the language system as definite units with definite structures. Besides, a similar vagueness can be-observed with regard to the demarcation line between complex sentences and combinations of sentences.

E. g. They are not people, but types. Which makes it difficult for the actors to present them convincingly. (D.W.).

Though coordinating conjunctions may be found to connect independent sentences, they are in an overwhelming majority of cases used to connect clauses.

As to the asyndetically connection of clauses, it is found both in compound and in complex sentences. In either case the relations between the clauses resemble those expressed by the corresponding conjunctions.

E.g. They had a little quarrel, he soon forgot. (London). Here the asyndeton might be replaced by which or but.

Semantically the clauses of a compound sentence are usually connected more closely than independent sentences. These relations may be reduced to a few typical cases that can be listed.

The order of clauses within a compound sentence is often more rigid than in complex sentences. He came at six and we had dinner together, (the place of the coordinate clauses cannot be changed without impairing the sense of the sentence).

Cf. If she wanted to do anything better she must have a great deal more. (Dreiser). She must have a great deal more if she wanted to do anything better.

Especially close is the connection of the coordinate clauses in a case like this.

He expected no answer, and a dull one would have been reproved. (Dreiser).

The prop-word one is an additional link between the clauses.

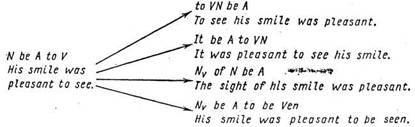

Though there is some similarity in the function and combinability of subordinate clauses and parts of the sentence, which is justly used as a criterion for the classification of clauses, we must not identify clauses and parts of simple sentences.

Apart from their having predications, clauses differ from parts of the simple sentence in some other respects, too.

a) Very often it is not the clause itself but the conjunction that defines its function and combinability. He speaks the truth may be a simple sentence, a coordinate or a subordinate clause, depending on the conjunction; and he speaks the truth is normally a coordinate clause, when he speaks the truth is often a subordinate clause of time, if he speaks the truth is mostly a subordinate clause of condition, etc.

Thus a conjunction is often a definite marker of a clause, which distinguishes such clauses from most English words having no markers. That probably accounts for the fact that clauses with such markers have a greater freedom of distribution than most parts of a simple sentence.

b) There is often no correlation between clauses and parts of simple sentences. I know that he is ill is correlated with I know that. I am afraid tint he is ill is not correlated with.

I am afraid that. I hope that he is well is not correlated with I hope that, etc.

The most important part of the sentence, the predicate, has no correlative type of clause.

Certain clauses have, as a matter of fact, no counterparts among the parts of the sentence.

E.g. I am a diplomat, aren't I? (Hemingway).

Похожие работы

... 4. One member sentences We have agreed, to term one-member sentences those sentences which have no separate subject and predicate but one main part only instead (see p. 190). Among these there is the type of sentence whose main part is a noun (or a substantives part of speech), the meaning of the sentence being that the thing denoted by the noun exists in a certain place or at a certain time. ...

... life and background, events that have influenced his or her writings or any literary classification (such as "romantic" or "politically/socially committed literature"). There is no doubt that for a translation-relevant text analysis translators must exploit all sources at their disposal. The translator should strive to achieve the information level which is presupposed in the receiver addressed by ...

... complications can be combined: Moira seemed not to be able to move. (D. Lessing) The first words may be more difficult to memorise than later ones. (K. L. Pike) C H A P T E R II The ways and problems of translating predicate from English into Uzbek. 1.2 The link-verbs in English and their translation into Uzbek and Russian In shaping the predicate the differences of language systems ...

... is not quite true for English. As for the affix morpheme, it may include either a prefix or a suffix, or both. Since prefixes and many suffixes in English are used for word-building, they are not considered in theoretical grammar. It deals only with word-changing morphemes, sometimes called auxiliary or functional morphemes. (c) An allomorph is a variant of a morpheme which occurs in certain ...

0 комментариев