Навигация

MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES IN TEACHING ENGLISH LEARNERS TO THE SENIOR FORMS OF SECONDARY SCHOOL

3.1. MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES IN TEACHING ENGLISH LEARNERS TO THE SENIOR FORMS OF SECONDARY SCHOOL

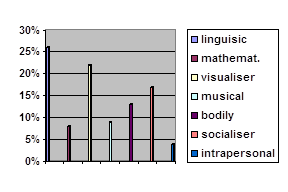

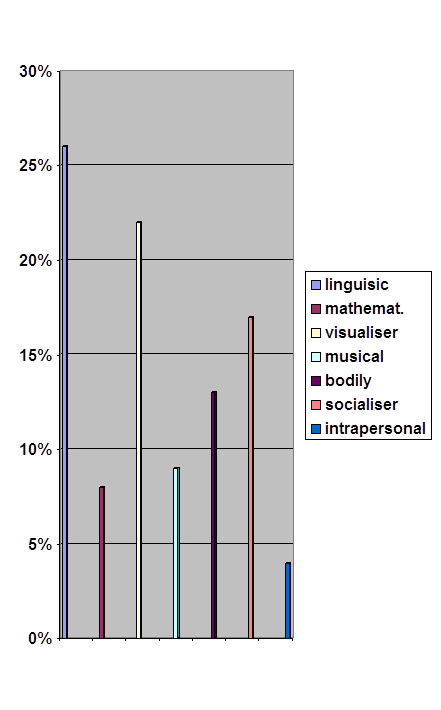

Accepting Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences has several implications for teachers in terms of classroom instruction. The theory states that all seven intelligences are needed to productively function in society. Teachers, therefore, should think of all intelligences as equally important. This is in great contrast to traditional education systems which typically place a strong emphasis on the development and use of verbal and mathematical intelligences. Thus, the Theory of Multiple Intelligences implies that educators should recognize and teach to a broader range of talents and skills.

Another implication is that teachers should structure the presentation of material in a style which engages most or all of the intelligences. For example, when teaching about the revolutionary war, a teacher can show students battle maps, play revolutionary war songs, organize a role play of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and have the students read a novel about life during that period. This kind of presentation not only excites students about learning, but it also allows a

teacher to reinforce the same material in a variety of ways. By activating a wide assortment of intelligences, teaching in this manner can facilitate a deeper understanding of the subject material.

Everyone is born possessing the seven intelligences. Nevertheless, all students will come into the classroom with different sets of developed intelligences. This means that each child will have his own unique set of intellectual strengths and weaknesses.

These sets determine how easy (or difficult) it is for a student to learn information when it is presented in a particular manner. This is commonly referred to as a learning style. Many learning styles can be found within one classroom. Therefore, it is impossible, as well as impractical, for a teacher to accommodate every lesson to all of

the learning styles found within the classroom. Nevertheless the teacher can show students how to use their more developed intelligences to assist in the understanding of a subject which normally employs their weaker intelligences . For example, the teacher can suggest that an especially musically intelligent child learn about the revolutionary war by making up a song about what happened.

As the education system has stressed the importance of developing mathematical and linguistic intelligences, it often bases student success only on the measured skills in those two intelligences. Supporters of Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences believe that this emphasis is unfair. Children whose musical intelligences are highly

developed, for example, may be overlooked for gifted programs or may be placed in a special education class because they do not have the required math or language scores. Teachers must seek to assess their students' learning in ways which will give an accurate overview of the their strengths and weaknesses.

As children do not learn in the same way, they cannot be assessed in a uniform fashion. Therefore, it is important that a teacher create an "intelligence profiles" for each student. Knowing how each student learns will allow the teacher to properly assess the child's progress . This individualized evaluation practice will allow a teacher to make more informed decisions on what to teach and how to present information.

Traditional tests (e.g., multiple choice, short answer, essay...) require students to show their knowledge in a predetermined manner. Supporters of Gardner's theory claim that a better approach to assessment is to allow students to explain the material in their own ways using the different intelligences. Preferred assessment methods include student portfolios, independent projects, student journals, and assigning creative tasks.

3.1.1 Development of students’ Speaking and Pronunciation Skills

Communicative and whole language instructional approaches promote integration of speaking, listening, reading, and writing in ways that reflect natural language use. But opportunities for speaking and listening require structure and planning if they are to support language development. This digest describes what speaking involves and

what good speakers do in the process of expressing themselves. It also presents an outline for creating an effective speaking lesson and for assessing learners' speaking skills.Oral communication skills in adult ESL instruction

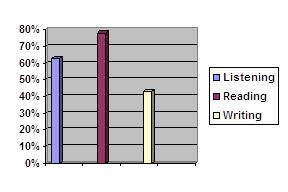

Outside the classroom, listening is used twice as often as speaking, which in turn is used twice as much as reading and writing . Inside the classroom, speaking and listening are the most often used skills . They are

recognized as critical for functioning in an English language context, both by teachers and by learners. These skills are also logical instructional starting points when learners have low literacy levels (in English or their native language) or limited formal education, or when they come from language backgrounds with a non-Roman script or a predominantly oral tradition. Further, with the drive to incorporate workforce readiness skills into adult EFL instruction, practice time is being devoted to such speaking skills as reporting, negotiating, clarifying, and problem solving .

What speaking is

Speaking is an interactive process of constructing meaning that involves producing and receiving and processing information . Its

form and meaning are dependent on the context in which it occurs, including the participants themselves, their collective experiences, the physical environment, and the purposes for speaking. It is often spontaneous, open-ended, and evolving.

However, speech is not always unpredictable. Language functions (or patterns) that tend to recur in certain discourse situations (e.g., declining an invitation or requesting

time off from work), can be identified and charted . For

example, when a salesperson asks "May I help you?" the expected discourse sequence includes a statement of need, response to the need, offer of appreciation, acknowledgement of the appreciation, and a leave-taking exchange. Speaking requires that learners not only know how to produce specific points of language such as grammar, pronunciation, or vocabulary (linguistic competence), but also that they

understand when, why, and in what ways to produce language (sociolinguistic

competence). Finally, speech has its own skills, structures, and conventions different from written language . A good speaker synthesizes this array of skills and knowledge to succeed in a given speech act.

What a good speaker does

A speaker's skills and speech habits have an impact on the success of any exchange .

Speakers must be able to anticipate and then produce the expected

patterns of specific discourse situations. They must also manage discrete elements such as turn-taking, rephrasing, providing feedback, or redirecting .

For example, a learner involved in the exchange with the salesperson described previously must know the usual pattern that such an interaction follows and access that knowledge as the exchange progresses. The learner must also choose the correct vocabulary to describe the item sought, rephrase or emphasize words to clarify the

description if the clerk does not understand, and use appropriate facial expressions to indicate satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the service. Other skills and knowledge that instruction might address include the following:

producing the sounds, stress patterns, rhythmic structures, and intonations of the language;

using grammar structures accurately;

assessing characteristics of the target audience, including shared knowledge or shared points of reference, status and power relations of participants, interest levels, or differences in perspectives;

selecting vocabulary that is understandable and appropriate for the audience, the topic being discussed, and the setting in which the speech act occurs;

applying strategies to enhance comprehensibility, such as emphasizing key words, rephrasing, or checking for listener comprehension;

using gestures or body language; and paying attention to the success of the interaction and adjusting components of speech such as vocabulary, rate of speech, and complexity of grammar structures to maximize listener comprehension and involvement .

Teachers should monitor learners' speech production to determine what skills and knowledge they already have and what areas need development. Bailey and Savage's New Ways in Teaching Speaking , and Lewis's New Ways in Teaching Adults offer suggestions for activities that can address different skills.

General outline of a speaking lesson

Speaking lessons can follow the usual pattern of preparation, presentation, practice, evaluation, and extension. The teacher can use the preparation step to establish a context for the speaking task (where, when, why, and with whom it will occur) and to initiate awareness of the speaking skill to be targeted (asking for clarification, stressing key words, using reduced forms of words). In presentation, the teacher can provide learners with a preproduction model that furthers learner comprehension and helps them become more attentive observers of language use. Practice involves learners in reproducing the targeted structure, usually in a controlled or highly supported manner. Evaluation involves directing attention to the skill being examined and asking learners to monitor and assess their own progress. Finally, extension consists of activities that ask learners to use the strategy or skill in a different context or authentic communicative situation, or to integrate use of the new skill or strategy with previously acquired ones (see supplement 4).

In-class speaking tasks

Although dialogues and conversations are the most obvious and most often used speaking activities in language classrooms, a teacher can select activities from a variety of tasks. Brown lists six possible task categories:

Imitative-

Drills in which the learner simply repeats a phrase or structure (e.g., "Excuse me." or "Can you help me?") for clarity and accuracy;

Intensive-

Drills or repetitions focusing on specific phonological or grammatical points, such as minimal pairs or repetition of a series of imperative sentences;

Responsive-

Short replies to teacher or learner questions or comments, such as a series of answers to yes/no questions;

Transactional-

Dialogues conducted for the purpose of information exchange, such as information-gathering interviews, role plays, or debates;

Interpersonal-

Dialogues to establish or maintain social relationships, such as personal interviews or casual conversation role plays; and

Extensive-

Extended monologues such as short speeches, oral reports, or oral summaries.

These tasks are not sequential. Each can be used independently or they can be integrated with one another, depending on learners' needs. For example, if learners are not using appropriate sentence intonations when participating in a transactional activity that focuses on the skill of politely interrupting to make a point, the teacher might decide to follow up with a brief imitative lesson targeting this feature.

When presenting tasks, teachers should tell learners about the language function to be produced in the task and the real context(s) in which it usually occurs. They should provide opportunities for interactive practice and build upon previous instruction as necessary (Burns & Joyce, 1997). Teachers should also be careful not to overload a speaking lesson with other new material such as numerous vocabulary or grammatical structures. This can distract learners from the primary speaking goals of the lesson.

Assessing speaking Speaking assessments can take many forms, from oral sections of standardized tests such as the Basic English Skills Test (BEST) or the English as a Second Language Oral Assessment (ESLOA) to authentic assessments such as progress checklists, analysis of taped speech samples, or anecdotal records of speech in classroom interactions. Assessment instruments should reflect instruction and be incorporated from the beginning stages of lesson planning . For example, if a lesson focuses on producing and recognizing signals for turn-taking in a group discussion, the assessment tool might be a checklist to be completed by the teacher or learners in the course of the learners' participation in the discussion. Finally, criteria should be clearly defined and understandable to both the teacher and the learners.

Improving secondary school graduates EFL Learners' Pronunciation Skills

Observations that limited pronunciation skills can undermine learners' self-confidence, restrict social interactions, and negatively influence estimations of a speaker's credibility and abilities are not new . However, the current focus on communicative approaches to English as a second language (ESL) instruction and the concern for building teamwork and communication skills in an increasingly diverse workplace are renewing interest in the role that pronunciation plays in adults' overall communicative competence. As a result, pronunciation is emerging from its often marginalized place in adult ESL instruction. This paper reviews the current status of pronunciation instruction in adult ESL classes. It provides an overview of the factors that influence pronunciation mastery and suggests ways to plan and implement pronunciation instruction.

Historical Perspective Pronunciation instruction tends to be linked to the instructional method being used . In the grammar-translation method of the past, pronunciation was almost irrelevant and therefore seldom taught. In the audio-lingual method, learners spent hours in the language lab listening to and repeating sounds and sound combinations. With the emergence of more holistic, communicative methods and approaches to EFL instruction, pronunciation is addressed within the context of real communication .

Factors Influencing Pronunciation Mastery

Research has contributed some important data on factors that can influence the learning and teaching of pronunciation skills.

Age. The debate over the impact of age on language acquisition and specifically pronunciation is varied. Some researchers argue that, after puberty, lateralization (the assigning of linguistic functions to the different brain hemispheres) is completed, and adults' ability to distinguish and produce native-like sounds is more limited. Others refer to the existence of sensitive periods when various aspects of language acquisition occur, or to adults' need to re-adjust existing neural networks to accommodate new sounds. Most researchers, however, agree that adults find pronunciation more difficult than children do and that they probably will not achieve native-like pronunciation. Yet experiences with language learning and the ability to self-monitor, which come with age, can offset these limitations to some degree.

Amount and type of prior pronunciation instruction. Prior experiences with pronunciation instruction may influence learners' success with current efforts. Learners at higher language proficiency levels may have developed habitual, systematic pronunciation errors that must be identified and addressed.

Aptitude. Individual capacity for learning languages has been debated. Some researchers believe all learners have the same capacity to learn a second language because they have learned a first language. Others assert that the ability to recognize and internalize foreign sounds may be unequally developed in different learners.

Learner attitude and motivation. Nonlinguistic factors related to an individual's personality and learning goals can influence achievement in pronunciation. Attitude toward the target language, culture, and native speakers; degree of acculturation (including exposure to and use of the target language); personal identity issues; and motivation for learning can all support or impede pronunciation skills development.

Native language. Most researchers agree that the learner's first language influences the pronunciation of the target language and is a significant factor in accounting for foreign accents. So-called interference or negative transfer from the first language is likely to cause errors in aspiration, intonation, and rhythm in the target language.

The pronunciation of any one learner might be affected by a combination of these factors. The key is to be aware of their existence so that they may be considered in creating realistic and effective pronunciation goals and development plans for the learners. For example, native-like pronunciation is not likely to be a realistic goal for older learners; a learner who is a native speaker of a tonal language, such as Vietnamese, will need assistance with different pronunciation features than will a native Spanish speaker; and a twenty-three year old engineer who knows he will be more respected and possibly promoted if his pronunciation improves is likely to be responsive to direct pronunciation instruction.

Language Features Involved in Pronunciation

Two groups of features are involved in pronunciation: segmentals and suprasegmentals. Segmentals are the basic inventory of distinctive sounds and the way that they combine to form a spoken language. In the case of North American English, this inventory is comprised of 40 phonemes (15 vowels and 25 consonants), which are the basic sounds that serve to distinguish words from one another. Pronunciation instruction has often concentrated on the mastery of segmentals through discrimination and production of target sounds via drills consisting of minimal pairs like /bæd/-/bæt/ or /sIt/-/sît/.

Suprasegmentals transcend the level of individual sound production. They extend across segmentals and are often produced unconsciously by native speakers. Since suprasegmental elements provide crucial context and support (they determine meaning) for segmental production, they are assuming a more prominent place in pronunciation instruction .

Suprasegmentals include the following:

stress-a combination of length, loudness, and pitch applied to syllables in a word (e.g., Happy, FOOTball);

rhythm-the regular, patterned beat of stressed and unstressed syllables and pauses (e.g., with weak syllables in lower case and stressed syllables in upper case: they WANT to GO Later.);

adjustments in connected speech-modifications of sounds within and between words in streams of speech (e.g., "ask him," /æsk hIm/ becomes /æs kIm/);

prominence-speaker's act of highlighting words to emphasize meaning or intent (e.g., Give me the BLUE one. (not the yellow one); and

intonation-the rising and falling of voice pitch across phrases and sentences (e.g., Are you REAdy?).

Incorporating Pronunciation in the Curriculum

In general, programs should start by establishing long range oral communication goals and objectives that identify pronunciation needs as well as speech functions and the contexts in which they might occur . These goals and objectives should be realistic, aiming for functional intelligibility (ability to make oneself relatively easily understood), functional communicability (ability to meet the communication needs one faces), and enhanced self-confidence in use . They should result from a careful analysis and description of the learners' needs . This analysis should then be used to support selection and sequencing of the pronunciation information and skills for each sub-group or proficiency level within the larger learner group .

To determine the level of emphasis to be placed on pronunciation within the curriculum, programs need to consider certain variables specific to their contexts.

the learners (ages, educational backgrounds, experiences with pronunciation instruction, motivations, general English proficiency levels)

the instructional setting (academic, workplace, English for specific purposes, literacy, conversation, family literacy)

institutional variables (teachers' instructional and educational experiences, focus of curriculum, availability of pronunciation materials, class size, availability of equipment)

linguistic variables (learners' native languages, diversity or lack of diversity of native languages within the group)

methodological variables (method or approach embraced by the program)

Incorporating Pronunciation in Instruction

Celce-Murcia, Brinton, and Goodwin propose a framework that supports a communicative-cognitive approach to teaching pronunciation. Preceded by a planning stage to identify learners' needs, pedagogical priorities, and teachers' readiness to teach pronunciation, the framework for the teaching stage of the framework offers a structure for creating effective pronunciation lessons and activities on the sound system and other features of North American English pronunciation.

description and analysis of the pronunciation feature to be targeted (raises learner awareness of the specific feature)

listening discrimination activities (learners listen for and practice recognizing the targeted feature)

controlled practice and feedback (support learner production of the feature in a controlled context)

guided practice and feedback (offer structured communication exercises in which learners can produce and monitor for the targeted feature)

communicative practice and feedback (provides opportunities for the learner to focus on content but also get feedback on where specific pronunciation instruction is needed).

A lesson on word stress, based on this framework, might look like the following:

The teacher presents a list of vocabulary items from the current lesson, employing both correct and incorrect word stress. After discussing the words and eliciting (if appropriate) learners' opinions on which are the correct versions, the concept of word stress is introduced and modeled.

Learners listen for and identify stressed syllables, using sequences of nonsense syllables of varying lengths (e.g., da-DA, da-da-DA-da).

Learners go back to the list of vocabulary items from step one and, in unison, indicate the correct stress patterns of each word by clapping, emphasizing the stressed syllables with louder claps. New words can be added to the list for continued practice if necessary.

In pairs, learners take turns reading a scripted dialogue. As one learner speaks, the other marks the stress patterns on a printed copy. Learners provide one another with feedback on their production and discrimination.

Learners make oral presentations to the class on topics related to their current lesson. Included in the assessment criteria for the activity are correct production and evidence of self-monitoring of word stress.

In addition to careful planning, teachers must be responsive to learners needs and explore a variety of methods to help learners comprehend pronunciation features. Useful exercises include the following:

Have learners touch their throats to feel vibration or no vibration in sound production, to understand voicing.

Have learners use mirrors to see placement of tongue and lips or shape of the mouth.

Have learners use kazoos to provide reinforcement of intonation patterns

Have learners stretch rubber bands to illustrate lengths of vowels.

Provide visual or auditory associations for a sound (a buzzing bee demonstrates the pronunciation of /z/).

Ask learners to hold up fingers to indicate numbers of syllables in words.

Похожие работы

... learners. Chapter 2 describes importance of using pair work and group work at project lessons. Chapter 3 shows how to use project work for developing all language skills. Chapter 4 analyses the results of the questionnaire and implementation of the project work “My Body” in form 4. 1. Aspects of Intellectual Development in Middle Childhood Changes in mental abilities – such as learning, memory, ...

... CLT: "Beyond grammatical discourse elements in communication, we are probing the nature of social, cultural, and pragmatic features of language. We are exploring pedagogical means for 'real-life' communication in the classroom. We are trying to get our learners to develop linguistic fluency, not just the accuracy that has so consumed our historical journey. We are equipping our students with ...

0 комментариев