Навигация

Problems of correcting students’ pronunciation

2.4 Problems of correcting students’ pronunciation

Look at these statements about correction of students' oral work. What do you think?

Advanced students need loads of correction, beginners hardly any. When you start to learn a language you need to be able to communicate imperfectly in lots of situations, not perfectly in a few. The teacher's job is to support learners as they blunder through a range of communicative scenarios, not badger them because they forget the third person -s. With advanced learners the opposite is usually the case.

The jury is out on the question of whether correcting students, however you do it, has any positive effect on their learning. There is some evidence, though, that time spent on correcting learners may be wasted.

Research into Second Language Acquisition has suggested that it may be that some language forms can be acquired more quickly through being given special attention while others may be acquired in the learners' own time, regardless of teacher attention. This helps explain, for example, why intermediate learners usually omit third person -s just like beginners, but often form questions with do correctly, unlike beginners.

There is little point correcting learners if they don’t have a fairly immediate opportunity to redo whatever they were doing and get it right.

Learners need the opportunity for a proper rerun of the communication scenario in which they made the error, if they are to have any chance of integrating the correct form into their English. Whether the error was teacher-corrected, peer-corrected or self-corrected in the first place is of relatively minor importance.

Lots of learners and teachers think correction is important.

Is this because it helps them to learn and teach or helps them to feel like learners and teachers?

The problem with some learners is they don’t make enough mistakes.

Accurate but minimal contributions in speaking activities are unlikely to benefit learning as much as inaccurate but extended participation. Learners can be hampered by their own inhibitions and attitudes to accuracy and errors, the teacher’s attitude and behaviour (conscious or unconscious) to accuracy and errors or the restricted nature of the activities proposed by the teacher.

Teachers spend too much time focussing on what students do wrong at the expense of helping them to get things right.

When giving feedback to learners on their performance in speaking English, the emphasis for the teacher should be to discover what learners didn’t say and help them say that, rather than pick the bones out of what they did say. This requires the use of activities which stretch learners appropriately and the teacher listening to what learners aren’t saying. That’s difficult. [18,74]

Correction slot pro-forma

Here is a sample correction slot pro-forma which has been filled in with some notes that a teacher took during a fluency activity for a pre-intermediate class of Spanish students:

Pronunciation

I go always to cinema

She have got a cat…

Does she can swim?

Swimming bath my fathers

“Comfortable”

“Bag”– said “Back”

intonation very flat (repeat some phrases with more pitch range)

Bodega

Ocio

Yo que se

I don't ever see my sister

Have you seen Minority Report?

Good pronunciation of AMAZING

Why use this pro-forma?

It helps teacher and students identify errors.

It helps you as a teacher to listen and give balanced feedback.

And how to use it ?

It has been divided into four sections. The first two, Grammar/Vocabulary and Pronunciation, are pretty evident and are what teachers look out for as 'mistakes' in most cases.

The third slot, L1, means the words that students used in their own language during the exercise. We believe that in a fluency-based activity, if a student can’t find the right word in English, they should say it in their own language so as not to impede the flow. An attentive teacher (who also knows her students' L1) will make a quick note of it and bring it up later, eliciting the translation from the class. If you are teaching a multi-lingual class, you can still use this column. You don’t have to know the translations. You can prompt the learners to come up with those. [19, 48]

The '#' column reminds us to include successful language in feedback. Too often in correction slots the emphasis is on what went wrong. Here the teacher can write down examples of good things that happened. This is especially true if the teacher notices that the students are using a recently taught structure or lexical item, or if they have pronounced something correctly that they had trouble with before.

Other suggestions

You can copy your filled-in version and hand it out to groups of students to save writing on the whiteboard. Or simply use it to help you note down language in an organized way.

You can fill out separate sheets for each group of students as you listen or even for each individual student (this would obviously work best with very small classes!). You can pass them round, have students correct their own, each others, whatever.

The advantage of using a set form is that by doing this, you keep an ongoing record of mistakes that can be stored and exploited for revision lessons, tests or as a filler for the end of a class. [20, 48]

Похожие работы

... a hundred years before the introduction of printing into England, could not have been very extensively circulated. A large specimen of it may be seen in Dr. Johnson's History of the English Language. Wickliffe died in 1384. The art of printing was invented about 1440, and first introduced into England, in 1468; but the first printed edition of the Bible in English, was executed in Germany. It was ...

... latter two implying disposal in deep water, if then alive by drowning; the arrangement for a killing may be a simple "contract", which suggests a normal transaction of business. One of the most infamous euphemisms in history was the German term Endlösung, frequently translated in English as "Final Solution" as if it were the consequence of a bureaucratic decision or even an academic exercise ...

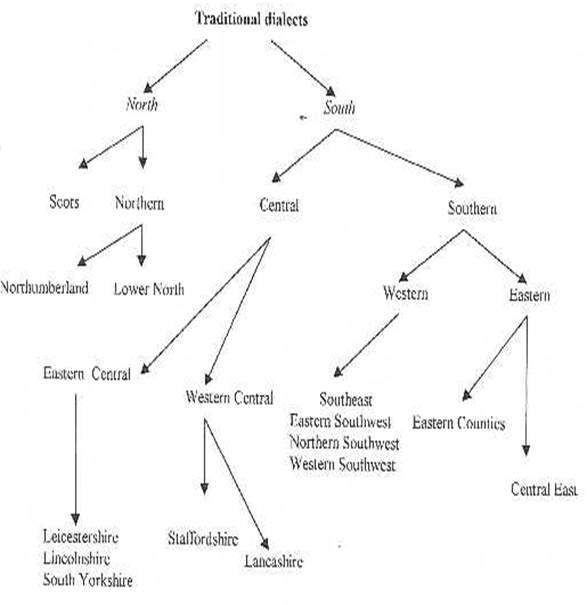

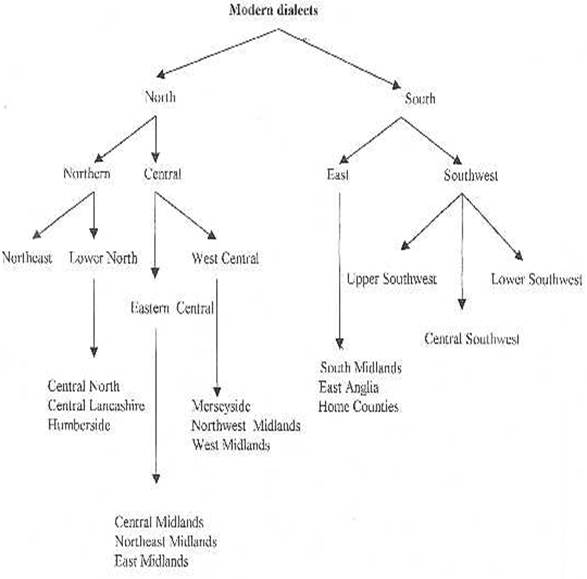

... . The pronunciation may seem rough and harsh, but is the same as that used by the forefathers; consequently it must not be considered barbarous. The other countries of England differ from the vernacular by a depraved pronunciation. Awareness of regional variation in England is evident from the fourteenth century, seen in the observation of such writers as Higden/Trevisa or William Caxton and in ...

... , what Partridge following Carnoy has called dysphemism. (48) Niceforo calls it "l'esprit de degradation et de depreciation," ("the spirit of degradation and depreciation") and goes on to speak of slang as a form of assault directed at a higher class by an underclass. (49) In its deliberate deformation of words, mispronunciation and taste for impropriety, slang may serve as the only act of ...

0 комментариев