Навигация

1. Plasmid Vectors

In 1952, Joshua Lederberg coined the term plasmid to describe any bacterial genetic element that exists in an extrachromosomal state for at least part of its replication cycle. As this description included bacterial viruses, the definition of what constitutes a plasmid was subsequently refined to describe exclusively or predominantly extrachromosomal genetic elements that replicate autonomously.

Figure 1. Joshua Lederberg

Plasmid vectors are convenient for cloning of small DNA fragments for restriction mapping and for studying regulatory regions. However, these vectors have a relatively small insert capacity. Therefore, a large number of clones are required for screening of a single-copy DNA fragment of higher eukaryotes. Second, the handling and storage of these clones is time-consuming and difficult. The repeated subcultures of recombinants may result in deletions in the inserts.

The plasmid vectors can be of three main types:

· generalpurpose cloning vectors,

· expression vectors,

· promoter probe or terminator probe vectors.

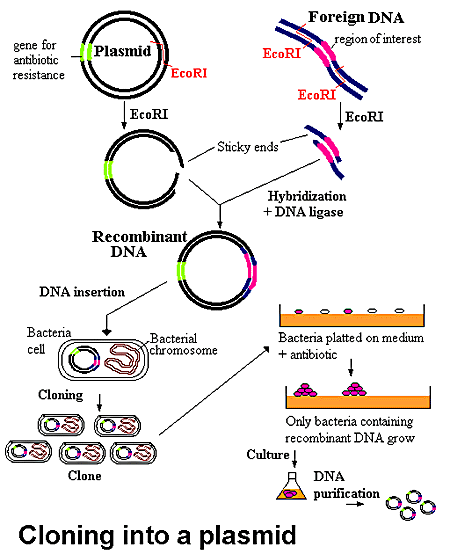

Figure 2. Cloning into a plasmid

General-purpose cloning vectors

Cloning of foreign DNA fragments in general-purpose cloning vectors [11] selectively inactivates one of the markers (insertional inactivation) or derepresses a silent marker (positive selection) so as to differentiate the recombinants from the native phenotype of the vector.

Expression vectors

In expression vectors, DNA to be cloned and expressed is inserted downstream of a strong promoter present in the vector. The expression of the foreign gene is regulated by the vector promoter irrespective of the recognition of its own regulatory sequence.

Promoter probe and terminator probe vectors

Promoter probe and terminator probe vectors are useful for the isolation of regulatory sequences such as promoters or terminators and for studying their recognition by a specific host. They possess a structural gene devoid of the promoter or the terminator sequence [8].

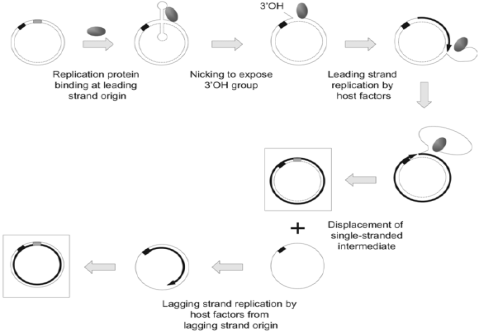

Figure 3. Replication of rolling-circle plasmids

2. Cosmids

A cosmid, first described by Collins and Hohn in 1978, is a type of hybrid plasmid (often used as a cloning vector) that contains cos sequences, DNA sequences originally from the Lambda phage. Cosmids can be used to build genomic libraries.

Cosmids are able to contain 37 to 52 kb of DNA, while normal plasmids are able to carry only 1–20 kb. They can replicate as plasmids if they have a suitable origin of replication: for example SV40 ori in mammalian cells, ColE1 ori for double-stranded DNA replication or f1 ori for single-stranded DNA replication in prokaryotes. They frequently also contain a gene for selection such as antibiotic resistance, so that the transfected cells can be identified by plating on a medium containing the antibiotic. Those cells which did not take up the cosmid would be unable to grow.

Unlike plasmids, they can also be packaged in phage capsids, which allows the foreign genes to be transferred into or between cells by transduction. Plasmids become unstable after a certain amount of DNA has been inserted into them, because their increased size is more conducive to recombination. To circumvent this, phage transduction is used instead. This is made possible by the cohesive ends, also known as cos sites. In this way, they are similar to using the lambda phage as a vector, but only that all the lambda genes have been deleted with the exception of the cos sequence.

Cos sequences are ~200 base pairs long and essential for packaging. They contain a cosN site where DNA is nicked at each strand, 12bp apart, by terminase. This causes linearization of the circular cosmid with two "cohesive" or "sticky ends" of 12bp. (The DNA must be linear to fit into a phage head.) The cosB site holds the terminase while it is nicking and separating the strands. The cosQ site of next cosmid (as rolling circle replication often results in linear concatemers) is held by the terminase after the previous cosmid has been packaged, to prevent degradation by cellular DNases.

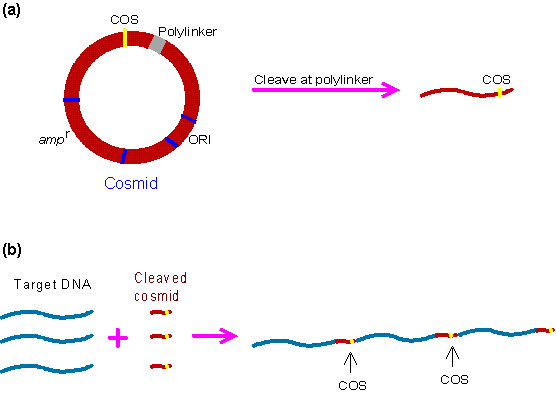

Figure 4. Cloning by using Cosmid method

Cosmid features and uses

Cosmids are predominantly plasmids with a bacterial oriV, an antibiotic selection marker and a cloning site, but they carry one, or more recently two cos sites derived from bacteriophage lambda. Depending on the particular aim of the experiment broad host range cosmids, shuttle cosmids or 'mammalian' cosmids (linked to SV40 oriV and mammalian selection markers) are available. The loading capacity of cosmids varies depending on the size of the vector itself but usually lies around 40–45 kb. The cloning procedure involves the generation of two vector arms which are then joined to the foreign DNA. Selection against wildtype cosmid DNA is simply done via size exclusion. Cosmids, however, always form colonies and not plaques. Also the clone density is much lower with around 105 - 106 CFU per µg of ligated DNA.

After the construction of recombinant lambda or cosmid libraries the total DNA is transferred into an appropriate E.coli host via a technique called in vitro packaging. The necessary packaging extracts are derived from E.coli cI857 lysogens (red- gam- Sam and Dam (head assembly) and Eam (tail assembly) respectively). These extracts will recognize and package the recombinant molecules in vitro, generating either mature phage particles (lambda-based vectors) or recombinant plasmids contained in phage shells (cosmids). These differences are reflected in the different infection frequencies seen in favour of lambda-replacement vectors. This compensates for their slightly lower loading capacity. Phage library are also stored and screened easier than cosmid (colonies!) libraries.

Target DNA: the genomic DNA to be cloned has to be cut into the appropriate size range of restriction fragments. This is usually done by partial restriction followed by either size fractionation or dephosphorylation (using calf-intestine phosphatase) to avoid chromosome scrambling, i.e. the ligation of physically unlinked fragments.

Похожие работы

... enable the seeds to survive the winter. Overwintering might allow the plant to become a weed or might intensify weedy properties it already possesses. Change in Herbicide Use Patterns Crops genetically engineered to be resistant to chemical herbicides are tightly linked to the use of particular chemical pesticides. Adoption of these crops could therefore lead to changes in the mix of chemical ...

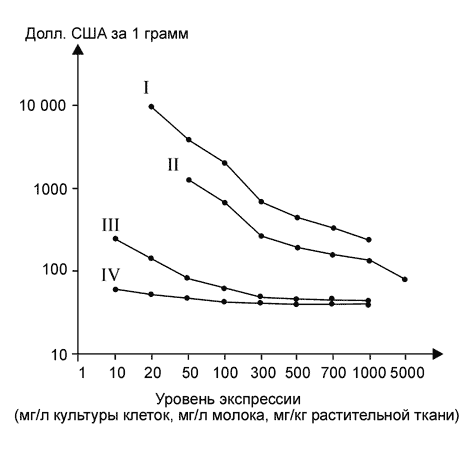

... растений позволит значительно снизить её стоимость (Giddings et al., 2000). В заключение хотелось бы отметить, что несмотря на значительные достижения в области продукции реком-бинантных белков медицинского назначения в растениях, это направление находится лишь на начальном этапе своего развития. Учёные-биотехно-логи уверены, что в будущем рекомбинантные препараты, получаемые из генетически ...

0 комментариев